As prices for gasoline, heating oil, electricity and natural gas skyrocketed during the 1970s, Americans increasingly explored alternatives to fossil fuel energy resources. In an effort to promote its mission of conservation, the Cleveland Metroparks opened a unique, state-of-the-art interpretation center that harnessed the power of the sun.

In 1976, the Cleveland Home and Flower Exposition drew a record crowd of nearly 100,000 persons during its opening weekend. The annual convention displayed the latest in landscaping techniques, construction materials and methods, and home furnishings. Eager consumers sauntered about the 250-plus exhibition booths and elaborate indoor gardens that temporarily adorned Cleveland's Public Hall. Inside the building, a canopy of trees jut out from a transplanted pastoral landscape embellished with waterfalls, rustic patios, windmills, greenhouses, flowering shrubs, and cobblestone walls.

Two full-scale model homes highlighted the show. A red cedar shake geodesic dome, called Fantasia, offered potential homeowners reduced building and heating costs by minimizing the structure’s surface area. The year’s main attraction, however, was a house designed by Neil William Guda of Shaker Heights. Equipped with “every possible energy-saving device,” the model home invited visitors to explore new ideas about energy efficiency. Refereed to as the "solar home," Guda's exhibit was slated for relocation in the Cleveland Metroparks North Chagrin Reservation at the close of the show. The underlying concept of the structure aligned with the Cleveland Metroparks long-standing mission to promote conservation, an idea that Clevelanders were increasingly willing to embrace.

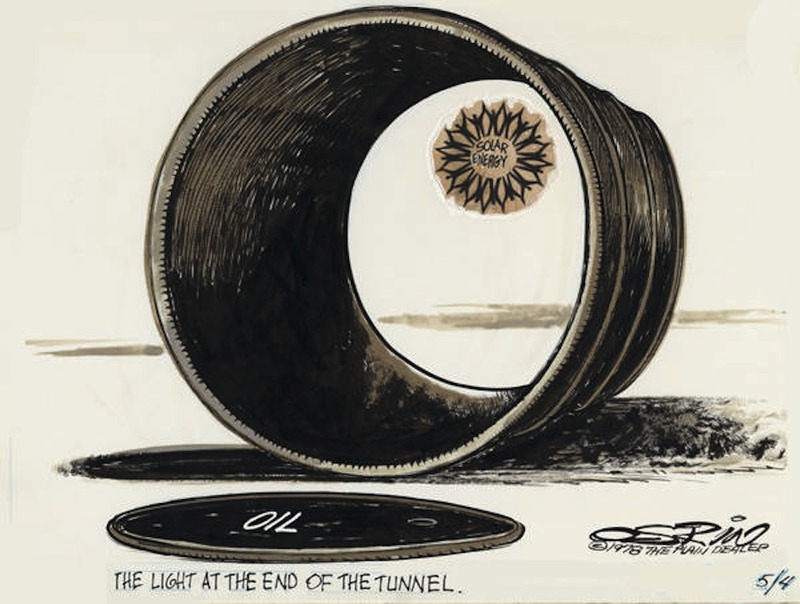

Public attitudes toward solar power, conservation, and environmentalism were changing. A nationwide “energy crisis” was leaving its signature on every facet of American life as prices for gasoline, heating oil, electricity and natural gas skyrocketed during the 1970s. Fossil fuel alternatives began to shed their counter culture stigma, and technologies for harvesting renewable, clean energy garnered public interest. The exposition's model home envisioned possibilities for the future of home design, and the potential of the wind and sun as practical energy resources - even during the bleakest of Cleveland winters.

Decades of postwar prosperity and voracious consumption had screeched to a halt just a few years prior to the 1976 Home and Flower Exposition. Although oil production in the United States had been outpaced by rising consumer demand since the late 1940s, prices were kept low in part by East Texas oil reserves. Coinciding with the decline of this oil surplus during the early 1970s, the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) imposed an oil embargo in 1973 on nations providing aid to Israel during the Yom Kippur/October War. Foreign petroleum producers also drastically raised benchmark prices, and the cost of oil quadrupled. Americans experienced fuel shortages for the first time since the days of World War II rations. The country's problems were not limited to high gasoline prices, though. America's infrastructure was built upon fossil fuel combustion, and the oil crisis lent a forceful hand in spiraling the United States into an economic recession. Industrial workers feared layoffs, over 20,000 gas stations closed, consumer goods inflated to offset transportation expenses, and the high cost of petroleum-based fuels was paralleled by skyrocketing electricity and natural gas prices.

Local, state, and national government officials quickly called upon citizens to conserve their resources. Speed limits were lowered, gas stations were asked to close on either evenings or Sundays, and governmental policies were drawn up to promote energy reform and reduce the nation's dependence on petroleum. The finite nature of fossil fuels and impact of over-consumption could no longer be ignored. As a national debate emerged over the development of petroleum alternatives, the environmental movement flourished and found a voice in shaping energy policy. In Washington, funding was generously allotted to researching alternative power sources. While the bulk of resources fell to advancing coal based fuels and nuclear fission plants, room was carved out in the budget for the promotion of wind and solar power technologies.

The promise of clean, renewable solar energy and wind power resonated with the public. The potential environmental toxicity of coal fuels and nuclear waste was not lost on Clevelanders already confronted with a burning river and dying lake. The energy crisis seemingly worsened each year, and it was believed that the world's supply of oil and natural gas was running out. The technology required to generate alternative energy, however, was new, untested and incredibly expensive. There was a lot of talk about the possibilities of passive and active solar-powered homes by 1975, but few prototypes had been constructed. A solar home erected on Ohio State fairgrounds in the fall of 1975 received mixed reviews; engineers were neither able to keep the house warm or water tank hot without utilizing supplemental power sources. Electricity and natural gas remained the cheapest energy options for heating and cooling homes.

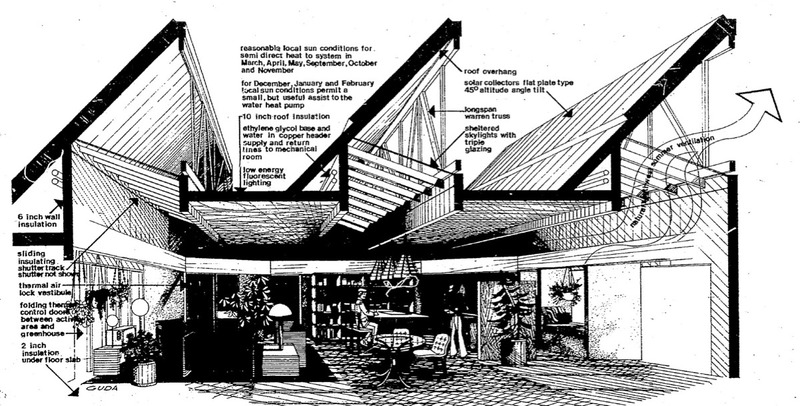

In Cleveland, builders turned to conservation techniques in order to stay afloat in the sinking economy. Residential designs became more compact, cathedral ceiling disappeared from new construction, and windows got smaller. The model home built for the Home and Flower Exposition in 1976 presented a myriad of additional energy saving options to realtors, homeowners, landscapers and construction companies. The house was meticulously designed to promote energy conservation. Among its many features were an electricity-generating windmill, a greenhouse acting as a solar collector, energy efficient air circulation, automated shutters, triple glazed windows, natural ventilation systems, and copious amounts of insulation lining the ceiling, floor and walls. The most intriguing characteristic of the house was a sawtooth roof pitched at 45 degrees, directing the surface of flat plate solar panels towards the sky. The home was conservatively estimated to reduce fuel bills by fifty percent, and could run for three days in dark weather.

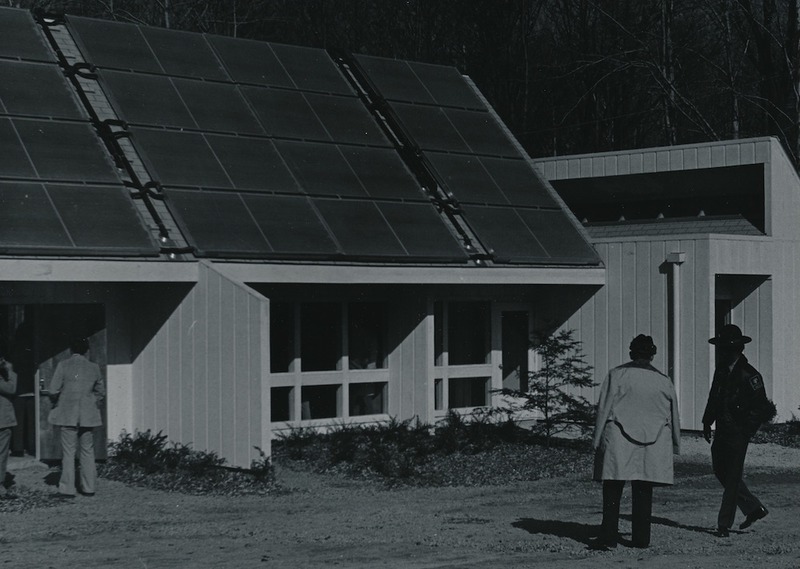

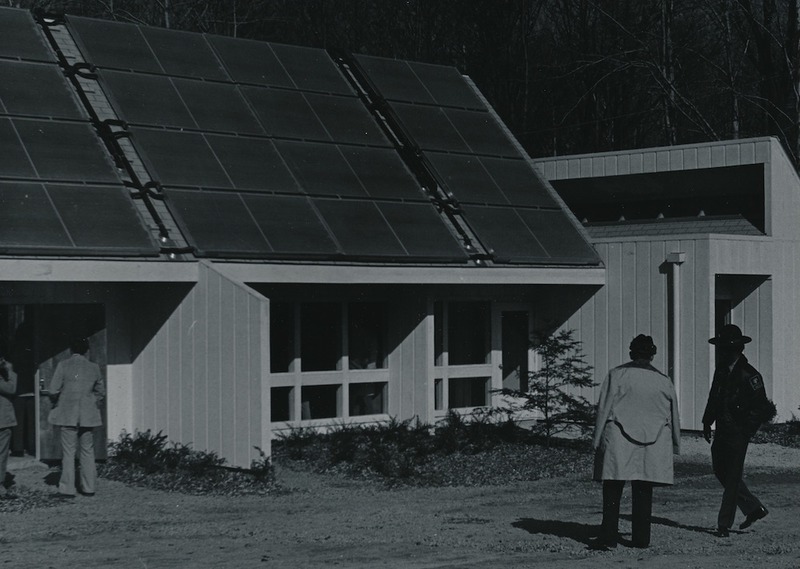

Valued at $100,000, not including land, the solar house was presented as a gift to the Cleveland Metroparks. The conservation-minded institution expressed a willingness to spend $50,000 for the structure's relocation, but it was soon discovered that the allotted funds would not cover the cost of excavating a foundation, laying utilities, and transporting the home. An additional $30,000 in finances was quickly acquired by the Metropolitan Park Board through a grant provided by the Cleveland Foundation. At the close of the Cleveland Home and Flower Exposition, the house was dismantled and trucked to the North Chagrin Reservation. The building was converted to accommodate the needs of the public and Cleveland Metroparks staff, and dedicated as the Solar Environmental Interpretive Center on October 29, 1976. As a Cleveland Metroparks interpretative educational center, the old solar home displayed the possibilities of conservation and energy efficiency.

On May 3, 1978, the Solar Interpretive Center hosted a public program entitled, "All You Ever Wanted to Know About Solar Energy and More." The day marked a new height for the 1970s alternative energy movement. Despite recent efforts to defund solar research by the Department of Energy, a joint resolution passed by Congress asked that President Jimmy Carter designate the date as "Sun Day." Polls showed that over 80% of Americans supported government development of solar energy, and it was purported that over thirty million people world-wide would participate in the festivities. Sunrise services, solar cookouts, speeches, concerts, and informational exhibits were planned throughout the country. To commemorate the day, President Carter visited a solar power research center; in his speech, he pledged to install a solar heat project at the White House. By September, plans were in place to install solar panels on the roof of the West Wing to power the White House kitchen's hot water heater. The new roof was unveiled to the public on June 20, 1979.

America's enthusiasm for alternative energies soon passed. A significant reduction in demand for oil, in part due to the successes of the energy conservation movement, helped stabilize prices in the 1980s. Additionally, new-found reserves of natural gas and petroleum eased fears over the depletion of the world's supply of fossil fuels. As the energy crisis came to a close, government funding for solar energy research was gutted. Many Americans eased back into complacent use of petroleum-based fuels, and the appeal of alternative energies waned. The solar water heating system at the White House was dismantled in 1986.

With the energy crisis abated, and the public's interest in solar power subsiding, North Chagrin Reservation's Solar Interpretive Center found new life as the Nature Education Building in 1984. The prior year, the Cleveland Metroparks announced a capital improvement plan to make its grounds more usable and comfortable for visitors. A new wildlife preserve and large interpretive nature center were to be constructed in the North Chagrin Reservation as part of the make-over. The Nature Education building was transformed to include touchable educational exhibits, classrooms, and laboratory space. While many of the energy efficient features were removed, the old solar home - sitting adjacent to Sanctuary Marsh and North Chagrin Nature Center - continues to embody the Cleveland Metroparks' mission of promoting the conservation of natural resources.

Images