The Great Cleveland Stockyards Fire

He was caught by chance. In early December 1945, Cleveland police officers had picked up and questioned two 14-year old girls on an unrelated matter. The girls mentioned a 12-year old boy in the neighborhood who had boasted about setting fires. The boy was brought in and he eventually confessed to setting the March 11, 1944 fire that the Cleveland Plain Dealer called "one of the most spectacular and disastrous" in the city's history. He said that he had done it for a thrill.

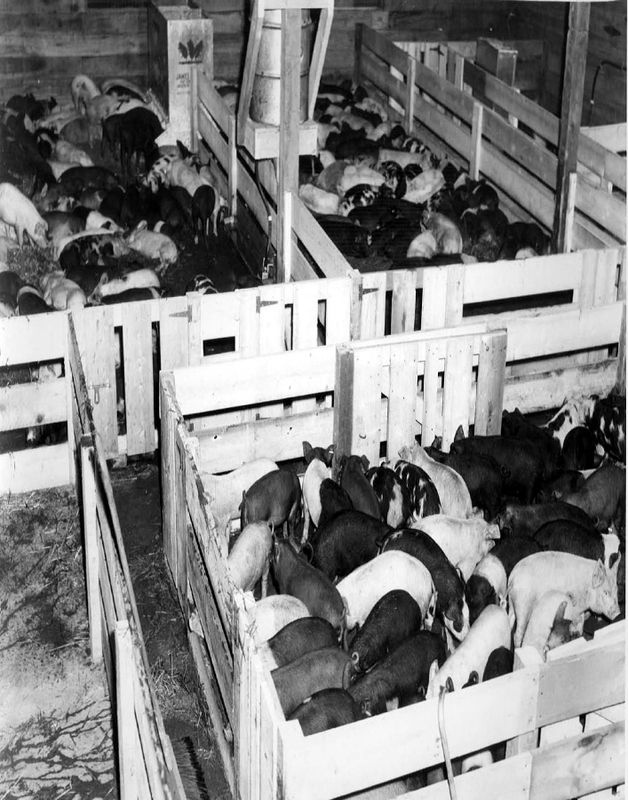

The fire that the boy set was at the Cleveland Union Stockyards on West 65th Street between the Big Four railroad tracks and Storer Avenue. It destroyed ten acres of pens and adjoining buildings on the stockyards' 40-acre property. Billowing black clouds of smoke from the fire could be seen for miles and prompted hundreds of people to call the Plain Dealer to find out what was burning. Newspaper accounts claimed that 25,000 people turned out to watch 15 Cleveland Fire Department engine companies battle the blaze for hours.

When it was all over, Cleveland firefighters Norman Kitzerow and Patrick Mangan lay dead and three other firemen had suffered life-threatening injuries in the fire fight. Over 100 animals--hogs and cattle, had died too, some in the blaze itself and others afterwards when, running crazed on W. 65th Street, they were shot dead by police armed with submachine guns.

Cleveland's stockyards hadn't always been as large as they were at the time of the Great Fire. Nor had they always been located on W. 65th Street. For most of the nineteenth century, a number of small stockyards existed in the city, with the largest of these in the Walworth Run valley near Columbus Street. In 1881, a group of Cleveland businessmen joined together to form the Cleveland Union Stockyards Company and aggregate the city's stockyards on a nine acre parcel of land on what was then considered the far west side of Cleveland. Adjacent lots were purchased in the decades that followed.

By 1926, the peak year of Cleveland Union Stockyards activity, one million hogs, 400,000 sheep, and 135,000 cattle were annually slaughtered there. In that era, the Stockyards were the third largest industry in Cleveland, each year doing fifty million dollars worth of business. It was also the seventh largest stockyard in the United States, and the largest between New York and Chicago.

In the short term, the Stockyards recovered from the 1944 fire. Employees were seen the next day building temporary pens on the site. But just as most Clevelanders in the 1940s didn't know that their city was already sliding toward decline, Stockyards officials didn't yet realize that the glory days of their enterprise were behind them. All around the country, large stockyards, including Cleveland's, were opening up smaller branch stockyards closer to other communities they served. And when companies like Swift & Co. decided in the 1950s and early 1960s to abandon Cleveland as a meatpacking center, the end for the Cleveland Union Stockyards was near.

Union Stockyards closed in 1968. Another entity, Cleveland Livestock Market Several, tried to keep the stockyards open and did so until 1974, when it ended its operations. The property was then sold, the pens and associated buildings were torn down, and a K-Mart was built on the site.

Images