Balto vs. the Alaskan Black Death

It was a race against time to save the city of Nome from the Alaskan Black Death. The only hope for the isolated, snowbound community was the delivery of diphtheria antitoxin by dog sled relay. An unlikely, fury national hero emerged from the treacherous serum run: Balto.

With seven children dead, nineteen persons severely ill and 150 under surveillance for infection with the Alaskan Black Death, the small city of Nome, Alaska was under quarantine. Nome's sole doctor moved house to house treating the sick, while a nurse attended to infected Eskimo children. A diphtheria epidemic threatened to decimate the icebound town of 1,400, and the only serum available had expired and proved ineffective.

In a race against time to save the city, the territorial Board of Health and Governor of Alaska moved to organize a relay of the area’s best dog sledding teams to transport a batch of serum by way of a postal route through the tundra. Newspapers in Cleveland and other urban centers latched onto the story. The public was reeled in with daily accounts of disease, blizzards, frostbite and subzero temperatures. Norwegian musher Gunner Kaasan and his sled team arrived in Nome with the life saving serum on February 5, 1925 at 5:30 A.M. Having traveled over 50 miles through treacherous weather, he stumbled into the doctor’s home, handed over the medicine and returned to his dogs. The only words he spoke before collapsing from physical exhaustion commended the lead of his sled team, Balto: “Damn fine dog.”

Balto quickly became an American hero and a symbol of the 1925 serum run. The story of the relay, and specifically one dog, had resonated with the public and created a sensation. Even though the disease had predominantly affected an indigenous population in what the press characterized as an uncivilized outpost, the course of events had struck a nerve in urban society. Both public interest in the serum run and Balto's rise to fame emerged from a nation's struggle to hold on to images of an idealized early American past. The run's captivating narrative was framed to portray the age-old theme of man versus nature, and the canine was inscribed with the values of the iconic 1920s hero - loyalty, courage and strength.

The 1925 serum run unfolded as a true-life pulp serial, and was shaped as a reflection of urban societies’ values and anxieties. The nation was adjusting to a change; for the first time in the 1920s, more than half of the population lived in cities. The growth of cities was both reinforced by and encouraged mass production and consumerism. In an era characterized by economic prosperity and increased leisure time for many urban residents, a new mass culture emerged. Entertainment flourished; radios, movies, printed media and advertising campaigns could reach and influence a wider range of the public. The changing face of the American landscape tied the country together as never before. The culture and identity of the nation became both associated with and representative of urban society. Tensions mounted as a nation’s social norms faltered under the highly visible influence of consumerism and materialism.

While urbanization had always been accompanied by a yearning for an idealized rural past, what seemed to be rapid steps towards modernity necessitated that a new American identity be forged. A moral world of yesteryear was drawn from constructed memories of frontier life. The bygone era was imagined to be a simpler and primitive time, a moment in the country’s history when men negotiated their own destiny. Representations of traditional values and belief systems, which by their nature were reactionary and defined in contrast to imagined current standards, were echoed in popular culture as a means to address the perceived moral pitfalls of urbanity.

The story of the serum run was formulated within the context of these unsettling social and cultural changes. Where technology had proved useless in the harsh wilderness, men battled through the forces of nature in a desperate attempt to save Nome's most vulnerable citizens. Hearkening back to America's lost frontier, the simple, moral tale emphasized the goodness and strength of its characters. The familiar narrative broached the works of Zane Gray and Edgar Rice Burroughs.

With the successful completion of the relay, the mushers were celebrated throughout Alaska. Leonhard Seppala and Gunnar Kaasan, both of Norwegian descent, found minor celebrity in United States. The run, however, came to be identified with Balto. An unlikely hero, Balto was aptly described in the newspapers as barrel-chested and inexperienced. Paralleling a common rags-to-riches theme, the dog had been used primarily for freight delivery and was never a lead on sled racing squad. Seppala, who owned and trained Balto, had passed over the dog for his own team.

Accounts of the relay often described Balto as only being chosen as the lead dog by Kaasan amidst a blizzard, when the former leader had proved ineffective in the adverse conditions. Balto's character and personality were formulated within a pattern of the typical 1920s hero. Described as courageous, strong and faithful, Balto joined the ranks of famous adventurers, athletes and protagonists of serials. The canine hero was featured in a Hollywood film and toured through America on the vaudeville circuit. A monument was erected of his likeness in Central Park, and the 'Balto' name was attached to books and advertisements.

The overshadowing success of Balto frustrated Leonhard Seppala, who was arguably the pivotal character in the success of the serum run. The men that had participated in the relay to save Nome, predominately either foreign born or indigenous to the area, had been relegated as background to Balto's story. Seppala believed that his lead racing dog, Togo, deserved the honors that were bestowed upon the second-rate freighting dog.

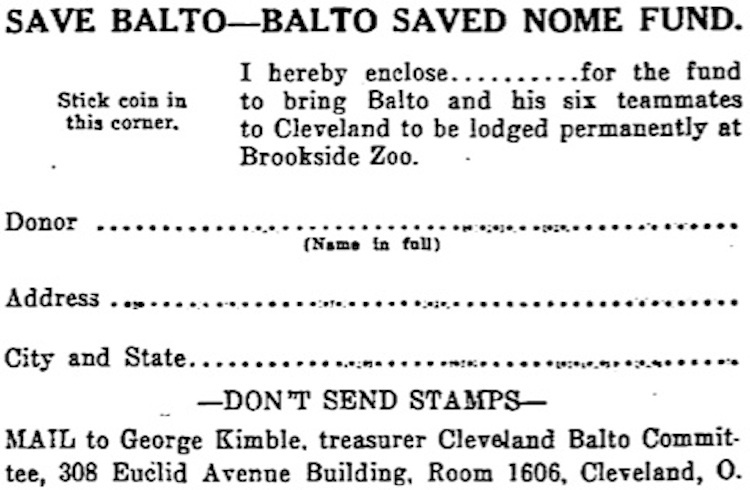

As both Kaasen's superior at the Pioneer Mining Company and the owner of Balto, Seppala ordered his subordinate back to Alaska in 1926. Balto and six teammates from the run were left in the hands of a tour promoter, who sold the dogs to a dime museum. Months later, Cleveland businessman George Kimble came across the dog team chained to a sled at the museum. Securing a price of $2,000 and two weeks to pay the museum owner, Kimble began a crusade to save the dogs. His campaign placed collection boxes throughout Cleveland in hotel lobbies, drug stores, Public Square, restaurants and cigar shops.

With the assistance of the Cleveland Plain Dealer in promoting the cause, Kimble raised over $2300.00 in 10 days. On March 19, 1927, the seven dogs were greeted with a parade through Public Square before being taken to their new home at the Brookside Zoo. An estimated 15,000 Clevelanders visited the sled team on their first day at the zoo, where Balto and his teammates lived out the remaining years of their lives as celebrities. A bronze tablet and granite monument inscribed with their names was dedicated in 1931. Originally erected to be a roster of heroic dogs and act as a shrine for animal lovers in Cleveland, the monument would be remembered as the gravestone of the dog pack.

Struggling with impaired mobility and a weak heart, Balto was euthanized on March 14, 1933 at the age of fourteen. Even in death, Balto’s celebrity as the dog that saved Nome endured. His body was mounted and placed on display at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, where it rivaled a collection of shrunken heads as the most requested exhibit. In a nod to the Husky’s famed bravery, his thyroid and adrenal glands were preserved in George Crile's organ collection at the Cleveland Clinic. With the pieces-parts of Balto’s corpse eternalized in Cleveland, public memory of the dog continued to be shaped nationally through books and film into the 21st century. Building off of the narrative created by the 1920s press, posthumous characterizations of the canine persisted in attributing the success of the Serum Run to his valor. The legend of Balto would withstand the test of time. The anthropomorphized hero acted as a furry reminder of an idealized pioneer past– a time when man, unaided by technology, battled against the forces of nature for survival and the advancement of civilization.

Audio

Images