In 1951, newspaper reporter Al Ostrow arrived at the Cleveland State Hospital and managed to get hired on the spot as an aide. He wrote about his time at the hospital in a series of articles for the Cleveland Press. The title of his exposé, "Whose fault is this?," provides the intent behind Ostrow's investigative reporting. His articles are riveting pieces of prose that keep readers on the edge of their seats. He describes an overcrowded hospital in desperate need of trained staff--both problems that they cannot seem to overcome. In order to embed himself in the hospital, Ostrow gave very little information of former jobs or places of residence, allowing him the opportunity to witness firsthand the indiscriminate hiring practices of the hospital.

As an aide, Ostrow was able to see for himself the kind of treatment patients received in the facility at the hands of their aides. He describes aides beating and restraining uncooperative patients. Ostrow's investigations furthered the efforts of those in the Cleveland community who wished to reform the mental hospital, but there were factors that impeded any change in the grand scheme of the hospital's organization and patient care.

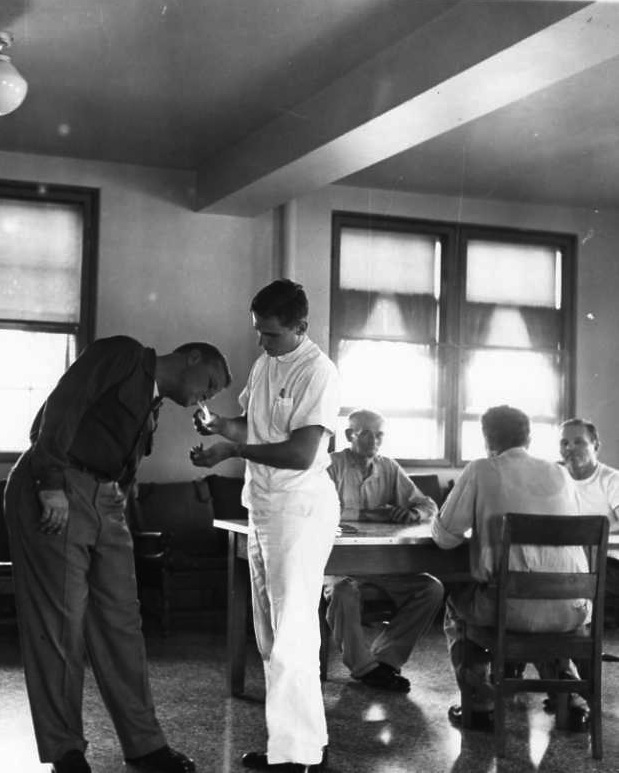

In 1955, only four years after Al Ostrow's stint in the Cleveland State Hospital as an aide, another Press reporter, Bus Bergen, was admitted as a patient. Previously, Bergen had gone undercover to pen an exposé on prison inmates. When Bergen arrived at the Cleveland State Hospital, he became patient no. 40591 under the assumed name Howard Berger, allegedly suffering from a mental illness. "Berger" spent time interacting with the patients as he lived with them and slept in the same cramped quarters. This view of the Cleveland State Hospital is even more upsetting than that of Ostrow's time as an aide because Bergen lived among the patients and had the opportunity to see them in an even more intimate setting.

Bergen describes the daily activities of the men in Ward C that are absolutely heartbreaking. Some patients carried around and fought over newspapers that were weeks old just to have something to pass the time. Cigarettes were used as currency and were often hard to come by. He describes patients who sat around all day with nothing to do, basically languishing in unkempt wards. Worst of all were the sleeping arrangements. Bergen describes hundreds of beds crammed into a large dormitory that range from two to 18 inches apart.

Such treatment of the mentally ill in state hospitals was hardly unique to Cleveland. State institutions all over the country as well as the state of Ohio had troubles with overcrowding due to an overwhelming number of new patients being admitted. For instance, the state hospital in Athens, Ohio, was known to have more than twice the number of patients than the building's capacity. Until exposés like those seen in Cleveland (as well as famous exposés nationally) started raising awareness of patient treatment, state hospitals were allowed to continue operating with poor conditions.

With exposés done by reporters like Bus Bergen and Al Ostrow, there was a significant amount of coverage in newspapers for everyday people to read about the lack of proper care in state hospitals. However, the trend of moving mental patients out of the state hospitals and back into the community was only considered once care conditions within institutions became more widely known and discussed. After World War II, a strong distrust of psychiatric facilities and scandals of controversial psychotherapies like lobotomies came to light that led to the idea of deinstitutionalizing patients and moving towards family or community care. This shift can be attributed to the increasing exposure of the type of care mentally ill patients received and the creation of medical associations founded to reform the medical community in general.

Images