Claes Oldenburg (1929-) and Coosje van Bruggen (1942-2009) were all about BIG; and the Free Stamp in Cleveland’s Willard Park is no exception. Inarguably the world’s largest office stamp, the aluminum and steel structure is 49 feet long, 28 feet high and weighs 70,000 pounds. In the Cleveland area, it’s one of three titanic installations created by Oldenburg and van Bruggen. The other two are Standing Mitt with Ball and Giant Toothpaste Tube, both of which reside in the Cleveland Museum of Art. Around the world, the couple’s monsterpieces include a 45-foot clothespin in Philadelphia, a ginormous badminton birdie in Kansas City and a gut-busting hamburger in Toronto. An electrifying three-way plug and a giant endomorphic Q are, respectively, on display in Oberlin and Akron, OH.

But Oldenburg and van Bruggen are even more than big: They also were humorists and social commentators, conceiving, among other things, a giant red lipstick tube atop tank treads for Yale University and a (never-realized) ballcock designed to float on the Thames River as if part of a giant toilet tank. Perhaps most important, however, Oldenburg and van Bruggen became sculptural disciples of a new form of expression, Pop Art, which appeared after the second world war and burgeoned by the 1960s. Pop Art emphasizes everyday (as opposed to high-culture) objects and images: paying tongue-in-cheek homage to society’s common or kitschy elements. Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein are just a few of the genre’s many giants.

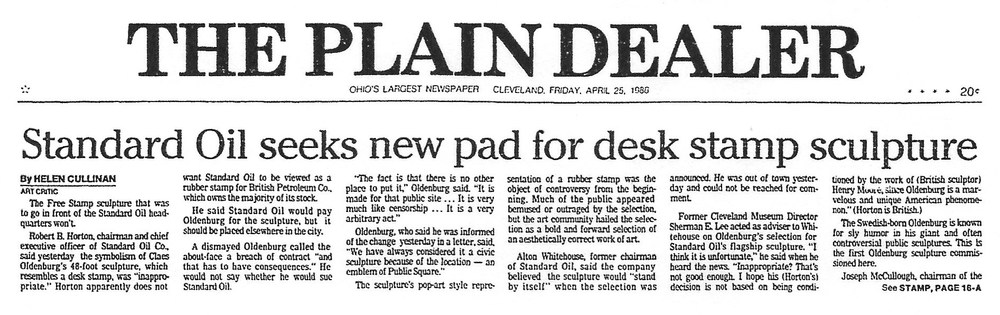

Unsurprisingly, the Free Stamp’s story is colorful and controversial. Commissioned by the Amoco Company in 1982, the Stamp was designed and fabricated in 1985. At the time, Amoco owned Sohio (Standard Oil of Ohio) and the building now known as 200 Public Square, and the piece was intended to reside in front of the building. But in 1986, before installation could happen, Amoco, Sohio and the building were acquired by BP America. The new owners refused to mount the sculpture—perhaps believing that “Free Stamp” was a metaphoric aspersion. Art historian Edward J. Olszewski has also noted that, in England, Pop Art is viewed more cynically and politically than in the United States, where it is considered primarily whimsical. Oldenburg is on record as saying that "free," references the emancipation of American slaves during and after the Civil War—a plausible explanation given the piece’s planned proximity to the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Monument.

So instead of adorning Public Square, the Free Stamp was denied its freedom: imprisoned instead in a warehouse in Illinois. There it gathered dust for five years before then-mayor George Voinovich invited Oldenburg and van Bruggen to Cleveland in hopes of selecting another site.

It eventually was decided that the Stamp should be located in Willard Park on Lakeside Avenue just west of East 9th Street; and BP agreed to gift it to the city of Cleveland with all installation and maintenance expenses covered. However, disagreements arose about how the sculpture would be positioned. The original intent was for the Stamp to stand face down on Public Square. However, Cleveland city planners felt that this approach was not right for Willard Park and the Stamp ultimately was mounted angularly, with the faux-rubber “FREE” proudly visible. According to Oldenburg, it was as if “a giant hand picked up the Free Stamp and angrily hurled it several blocks to its current location at Willard Park." Not surprisingly, the Stamp—formally dedicated on November 15, 1991—aims directly at 200 Public Square “It’s pointed on a diagonal to the 23rd floor, which were [BP’s] corporate offices,” notes Olszewski. “It leads the viewer back to the original site.”

Free, of course, is almost never free. The Stamp received its first maintenance treatment (interior and exterior painting and rust removal, etc.) in 1998. Its next spa treatment, in 2014, cost $96,000 which, in an ironic (but previously agreed-upon) turn, was paid by BP America.

Images