Church of the Covenant

The Church of the Covenant grew out of the merger of three Presbyterian congregations: Second Presbyterian (established in 1844), Euclid Street Presbyterian (1853), and Beckwith Memorial Presbyterian (1885). In 1903, Beckwith Memorial Presbyterian Church was confronted with financial misfortune. Beckwith’s congregation discovered the church had accumulated $1,200 in debt. In November of 1903, Beckwith pastor James D. Williamson spoke with the congregation in a special meeting about the benefits of merging Beckwith with Euclid Street Presbyterian Church, which was also experiencing tough times as a result of construction-related difficulties. Construction debts did not get paid off until 1871, and the construction itself turned away people who were looking for a new place of worship because of the prolonged project. On November 3, 1906, the two churches finalized the merger and would become known as the Euclid Avenue Presbyterian Church.

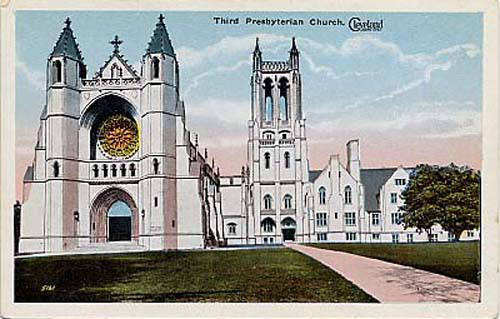

On May 1, 1907, the Euclid Avenue Presbyterian Church’s building committee summoned six architectural firms to design a new church. The church selected Cram, Goodhue, and Ferguson of Boston and New York and hired Cleveland architect John W.C. Corbusier to supervise the construction. In June 1909, the construction of the church commenced. The total cost of the construction of this new church was nearly $400,000. The church was designed in the English Gothic style, built using limestone, and had a grand 140-foot tower. The Euclid Avenue Presbyterian Church was completed in 1911 in its new location at 11205 Euclid Avenue.

During World War I, Cleveland saw a surge in its African American population. Most newly relocated African Americans to Cleveland settled in the Central and Woodland neighborhoods. This movement into these neighborhoods caused white residents to relocate to Cleveland’s suburbs. These changes affected Second Presbyterian, located at Prospect Avenue and East 30th Street. In 1915 the church achieved its highest membership with 971 members. Even though the church had a record number of members, church leaders contemplated a move to better serve their congregation that was leaving the city. On November 10, 1919, church elders would reevaluate the issue about the church moving. Instead, in 1920, Second Presbyterian and Euclid Presbyterian merged to form the Church of the Covenant.

The Church of the Covenant wanted to become more community-oriented, and on February 20, 1928, the church installed Philip S. Bird to take charge of this mission. Bird took on the task of bringing the congregations together, but many church members still saw themselves as two separate congregations. With the intention of bringing the church together, Bird built the church’s outreach into the community. Bird believed no matter one’s educational, social, and economic background, all are equal in God’s sight. The church’s outreach was not just for the city of Cleveland; Bird continued the church’s tradition of helping a hospital in rural North Carolina. Bird also expanded the church’s outreach to India. The church gave money to missionaries that taught farming methods in India and opened hospitals in China.

Amid the Great Depression, the church still helped the community. During the depression, Bird and Gertrude Wheaton spoke about using Covenant’s League for Service to help the community. The church’s League for Service helped some of Cleveland’s social organizations like the Salvation Army, Phillis Wheatley Association, the Woodland Center, Home for Aged Colored People, Alta House, Playhouse Settlement day nursery, and University and City Hospitals. Covenant’s League for Service helped give baths, clean, and feed the people the organization helped. The church started its soup kitchen and passed out food to the needy.

In 1947 Bird’s last move as pastor of the church was to create the Covenant Weekday Nursery School. He appointed Eleanor Dotson to lead the school. The majority of the kids came from the surrounding apartments. The school gave these children a chance to play. The school services were available to all kids, no matter their race, economic background, and religious beliefs. The school experienced significant growth over the years and had to expand its days. With the massive growth of enrollment, the school needed more workers. The school helped create jobs for the surrounding community. After twenty years of service at the Church of the Covenant, Bird retired in 1948. Bird would pass the reins of the church to Pastor Harry Bertrand Taylor in 1949. Under Taylor’s leadership, the Church of the Covenant continued its role in social change. Taylor continued to fund Bird’s outreach programs locally and overseas. Taylor expanded the outreach programs that supported medical missionaries in Asian countries. Under Taylor, the church still supported local hospitals by donating blankets, baked goods, and their services to help people in need.

The Church of the Covenant became a pioneer during the Civil Rights era by having racially integrated services. In 1951 the church gained its first African American member, J. Harold Brown, who was the Director of Music at Calmer House. Brown asked Dargan Burns to join the church with him. Once Brown and Burns became members, more African Americans joined. Burns received a cold reception at his first service at the church. Some church members were not fond of African Americans who joined the church, but others welcomed the new members. During a meeting of church elders, some elders voiced concern about African Americans being allowed to join. Taylor expressed to church elders that if they had a problem with African Americans joining, they had better find a new pastor. Covenant became home to a widely dispersed congregation as a result of changing neighborhood demographics in the second half of the 20th century. Taylor would open more leadership ventures to women members. In 1957 the Church of the Covenant elected Helen Baldwin to church elder; this move made Baldwin the church’s first woman elder.

Taylor continued fighting for racial equality and integration in Cleveland. Taylor’s fight against racism would cause trouble for the church. According to an audit of the church, it fell short of reaching its pledge donation goal. Some members said they cut or did not donate money because of Taylor’s and the church’s stance on the civil rights movement. Many believed that the church should stay out of the Civil Rights movement. Nevertheless, Taylor and the church continued the fight against racism.

On February 15, 1966, Taylor submitted his letter of resignation to the church, and he preached his last sermon on June 27 of that year. After Taylor, the Church of the Covenant would have many more pastors like him with the same community-first mindset, ensuring that the Church of the Covenant would continue to have an instrumental impact on faith-based commitments to social justice.

Audio

Images