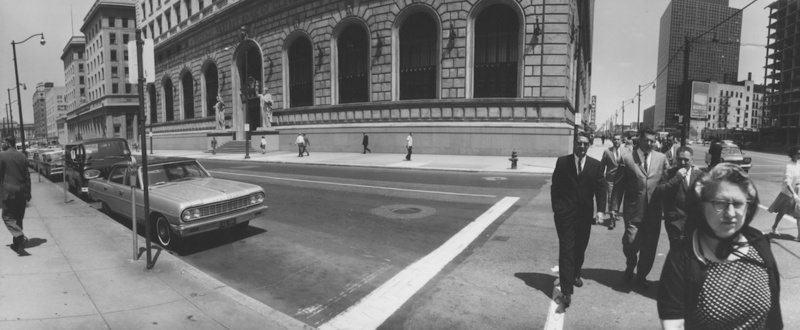

Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland

Spanning more than 200 feet along Superior Avenue and East 6th Street, the thirteen-story Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland sits comfortably among neighboring Group Plan structures in the city's Civic Center district. The building is a reminder of an era of unprecedented urban growth in Cleveland, and of the federal government's fledgling control over a central banking system.

Following the Wall Street Panic of 1907, a movement for banking reform increasingly appealed to citizens distrustful of banks and bankers. In response, Congress created the National Monetary Commission in 1908. The committee recommended the development of a central banking system that could issue currency. After years of debate, what is now called the Federal Reserve Act was passed in 1913. It called for the creation of eight to twelve autonomous Federal Reserve Banks, to be owned by the banks in the region each Federal Reserve Bank would represent. The actions of the banks were to be coordinated by a Federal Reserve Board appointed by the President. The primary function of these privately owned, but publicly controlled, institutions was to be a lender of last resort.

One of the twelve member banks was slated for Cleveland. Following its 1914 establishment, the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland was housed on the second floor of the Williamson Building overlooking Public Square. It served the Fourth District of the Federal Reserve: member banks in Ohio and parts of Pennsylvania and West Virginia. The Cleveland branch quickly became the third largest of the twelve Federal Reserve banks, forcing the institution to expand to multiple floors of the Williamson Building.

In 1919, the architectural firm of Walker & Weeks was hired to design a new home for Cleveland's branch of the Federal Reserve. Four architects and a team of draftsmen worked for thirteen months on the design. One thousand sketches and nearly 2,000 blueprints were prepared for the new structure. Construction began in 1921. Two years and $8.25 million later, the Fourth District Federal Reserve Bank formally opened on August 23, 1923, an event attended by an estimated crowd of 40,000.

The pink Etowah Georgia marble building fits well with the Beaux-Arts character of neighboring Group Plan buildings, such as the Cleveland Public Library and Public Auditorium. Inspired by the Medici palace in Florence, the Federal Reserve Building is reminiscent of a modern Italian Renaissance palazzo.

The grandeur of the bank's exterior is equaled or even surpassed by the intricately detailed lobby. Gold marble walls and pillars complement the ornate iron grilles that protect twelve large ground-floor arched windows. The vaulted ceiling and layout remind one of a Roman basilica. Dignified statuary, paintings, and ironwork speak to the history of the Federal Reserve institution and the ideals underlying its development.

Beyond its classical lines and elaborate interior, the building’s other design mission was to communicate soundness and safety. Exacerbated by several financial panics, people’s trust in banks waned in the early 20th Century. The Federal Reserve System was created to stem these concerns, but the physical demonstration of security was equally important. Toward this end, the Cleveland facility’s fortress-like structure includes hidden gun ports and observation windows and slots for sharpshooters under the third step of the main entrance. It also is purported that small artillery cannons or revolving gun turrets are hidden beneath the base of the statues at the building’s entrance. Inside, the two-story vault has concrete walls 6.5 feet thick. The bank vault door—100 tons and five feet thick—is the largest of its kind in the world.

All in all, the building—inside and outside—seems to say “Not only is your money safe but it’s living better than you are.” What’s more, you’re welcome to go visit your money, or at least see where it’s hanging out: Check the Federal Reserve Bank website for tour hours.

Images