Oghema Niagara of the band Pishqua, tribe Osauckee of the Algonquin nation, was born amid the thunderous sound of the Niagara on September 10, 1865, in the Hut of Two Kettle on the Tuscarora Indian Village in Lewistown, New York. Cleveland became his home during the first decade of the 20th century. He came to be known among white men as Chief Thunderwater and built an impressive career as a business leader and civic booster while maintaining his native identity.

As a member of the Pioneers Memorial Association, Chief Thunderwater led a long crusade to save the Erie Street Cemetery from relocation/desecration with a warning that "should the body of [Mesquakie chief and cemetery resident] Joc-o-Sot’s ever be touched, a terrible disaster would befall Cleveland." It would not be his last or even most famous prophecy. He also claimed, ex post facto, to have seen a vision in 1948, correctly predicting a World Series win by the Cleveland Indians baseball team. It is unknown whether the Chief was sincere or if, understanding the strange condition of native peoples in modern North America, he was merely playing the expected role of mystic. After all, Oghema Niagara had an agenda.

Born and raised during the final stages of the Indian Wars, he knew that adopting the ways of white men came with both opportunity and risk. Native Americans who entered white society were expected – and often forced – to abandon native cultural practices. Oghema Niagara learned that if he were to preserve his culture, he would need to understand what white Americans saw as important. It is likely his experience as a performer in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show gave him some idea of how to proceed. By showcasing (sometimes imagined or invented) native ways, he sought to promote the humanity of native people and demonstrate the value of traditional cultures. Along the way, he also made the social connections that would help establish him among the burgeoning Cleveland business class and lend him the influence he needed to serve as a voice for his people.

Chief Thunderwater began selling herbal cure-alls in Cleveland in the early 1900s. His products – including "Mohawk Penetrating Oil," "Thunderwater Tonic Bitters," "Seminole Sweet Gum Salve," and "Jee-wan-ga tea," – were supposedly derived from traditional medicines "from back in the days when bison trampled the prairie flowers in the dust." He ran his own Thunderwater & Rose company and served as president of the Preservative Cleaner Company, a manufacturer of polishes. He belonged to the Cleveland Business Men's Taft Club, made up of Republican Party supporters, and personally met Presidents Wilson and Taft. His 17 room dwelling at 6716 Baden Court served as his business headquarters. It also became a de facto inn for traveling Native Americans and an occasional home for those in need.

Oghema Niagara was Cleveland’s last known "sachem" and served as a founder and leader of the Supreme Council of Indian Tribes from 1917 to 1950. During that period, he addressed Indian affairs from his home and often travelled thousands of miles to personally diffuse situations throughout North America. He lectured vigorously in support of American Indian rights, leading the fight, for example, in United States, Ex Rel. Diabo vs. McCandless regarding the border between the U.S. and Canada and Indian acknowledgement thereof. Thundering against the "wrongs that the white man did unto his red people," Oghema Niagara led The Thunderwater Movement, which agitated for, among other things, unification of the tribes for the purpose of securing an independent Indian Nation roughly the size of Texas. In the latter half of his life, he was a consistent and controversial figure in the still-nascent movement for Native American rights, butting up against the repressive policies of the Indian Affairs office in the US and the Indian Department in Canada, as well as more assimilationist Native Americans.

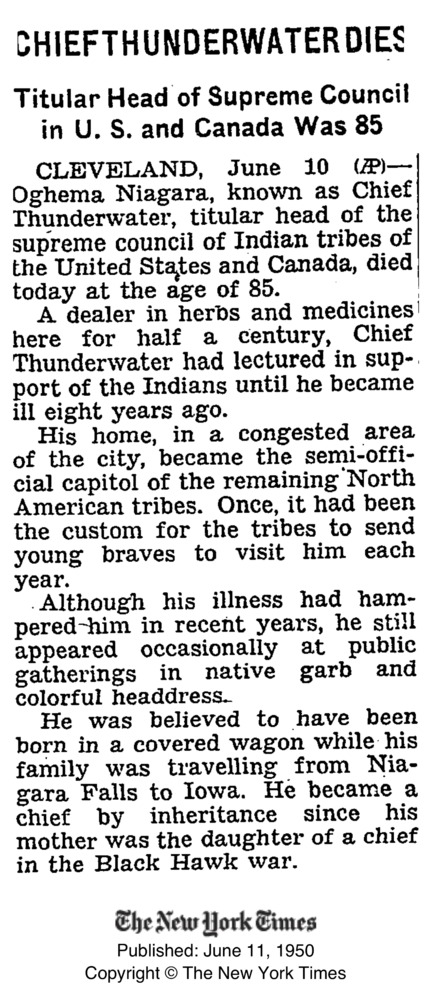

By the time of his death on June 10th of 1950, Chief Thunderwater had become something of a ceremonial celebrity in Cleveland, at least in part thanks to the name of the local baseball team, for which he rooted near the end of his life ("May the best warriors win, as long as they are Cleveland's" he declared prior to the Indians' 1948 World Series win). Some claim he was the inspiration for the team's racially-insensitive Chief Wahoo mascot, an indignity imposed on the memory of a handful of other Native American Clevelanders, including baseball players Allie Reynolds and Louis Sockalexis. The Canadian government claimed he was not a Native American at all, but a "negro" conman named Henry Palmer – a charge his supporters (plausibly) considered a transparent fabrication meant to discredit the Pan-Indian Thunderwater Movement.

Chief Thunderwater, Henry Palmer, Oghema Niagara, is buried at Erie Street Cemetery, a place he helped preserve, alongside the unmoved grave of Chief Joc-o-Sot.

Images