"I should not want this fact . . . [that he was an African American] . . . to be stated in the book, nor advertised unless the publisher advised it; first, because I do not know whether it would affect its reception favorably or unfavorably, or at all; secondly, because I would not have the book judged by any standard lower than that set for other writers. If some of these stories have stood the test of admission into the Atlantic and other publications where they have appeared, I am willing to submit them all to the public on their merits." Letter of Charles W. Chesnutt to Houghton, Mifflin & Co., Summer of 1891.

Charles W. Chesnutt was the first commercially successful African American fiction writer. While he experienced much early success with the short stories he penned in the last two decades of the nineteenth century, his efforts at the beginning of the twentieth century to become equally successful as a novelist failed because of the unwillingness of the American public to buy a sufficient number of his books. America was at that time just not yet ready for novels that exposed at length and in great detail the ugliness and ridiculousness of the "color line" that then existed in the U.S., a line which—though applied in different ways in the North and South—nonetheless in all places limited African Americans from fully exercising their rights and liberties, simply because of the color of their skin.

After the commercial failure in 1905 of his third novel, The Colonel's Dream, Chesnutt, at age 47, gave up on his dream—with that novel being the final one published during his lifetime. Had Chesnutt's contemporary, Mark Twain, been similarly discouraged in his literary career at a similar age, many of his novels that we have all come to know, love and cherish, would never have been written. Following Chesnutt's death 27 years later in 1932, his works were, for decades, largely forgotten. In the 1960's, they experienced a short-lived revival, but it wasn't until the early twenty-first century that critics and readers alike finally began to recognize the literary brilliance of his work and his unique insights into the problems of race in America in the post-Civil War/pre-Harlem Renaissance period.

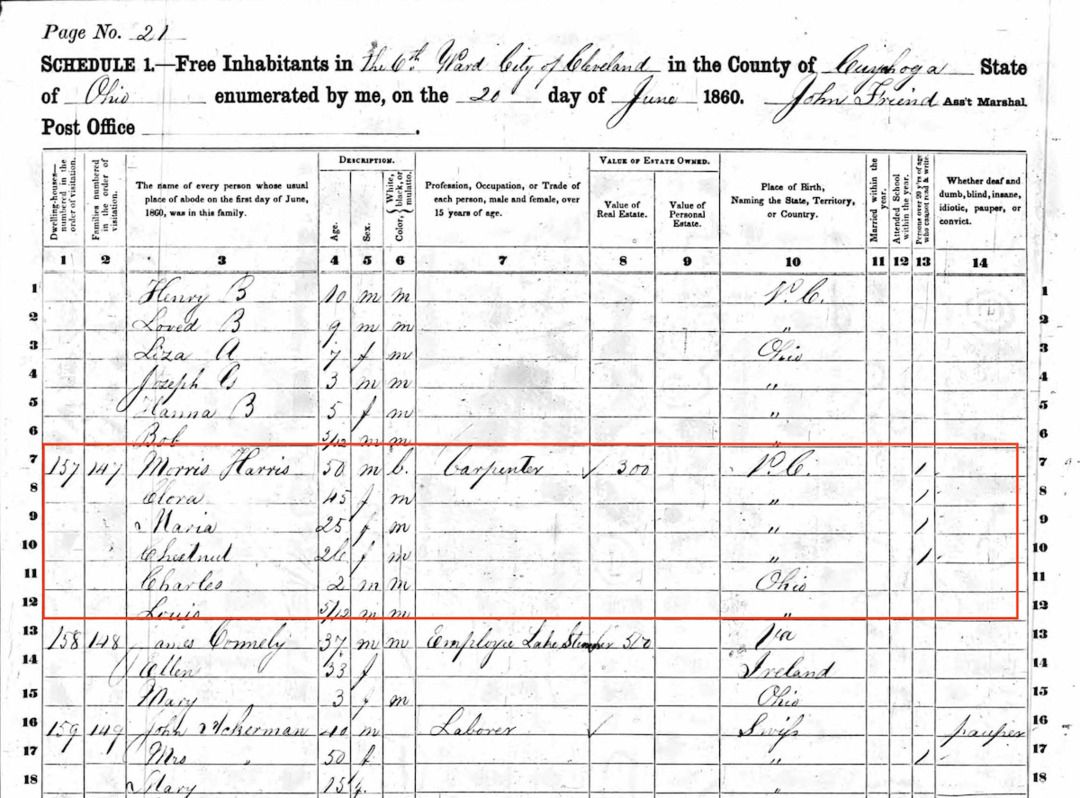

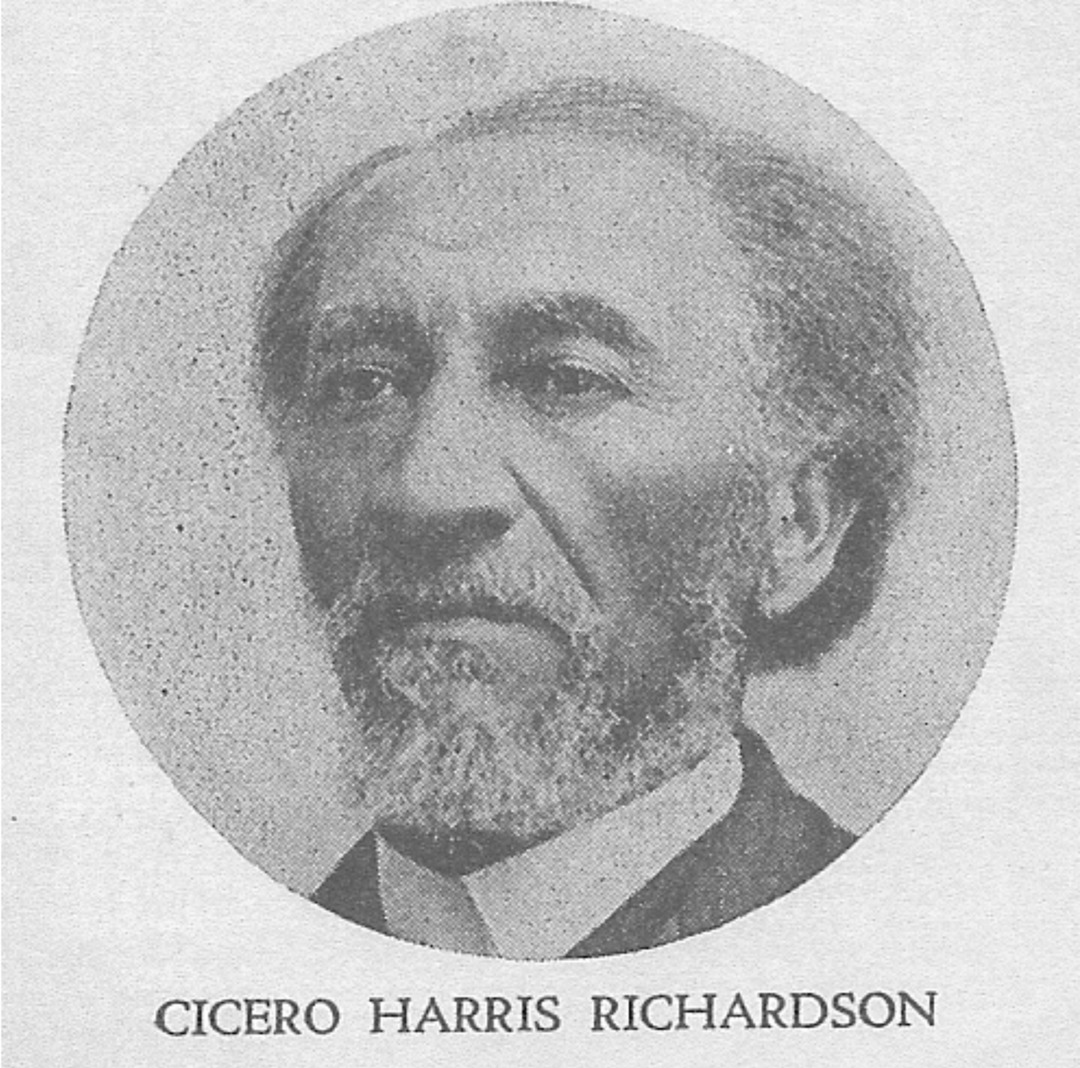

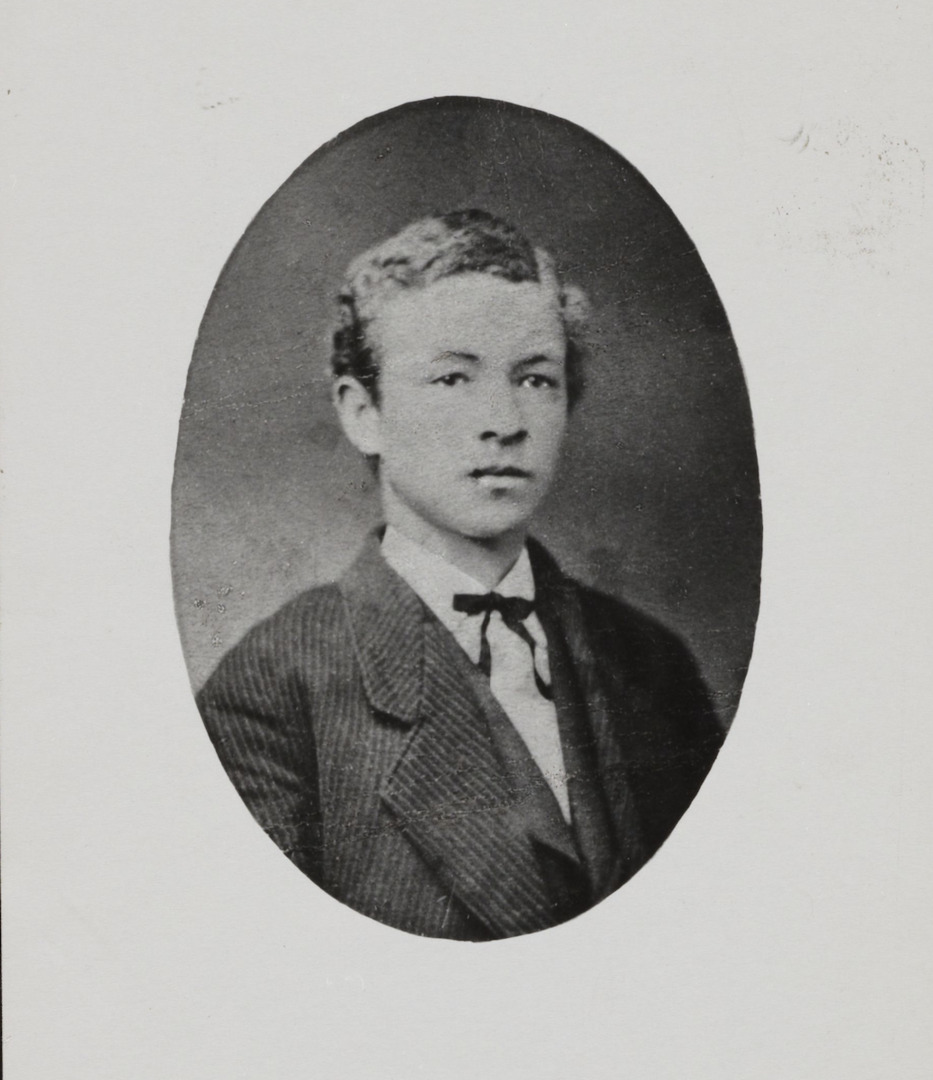

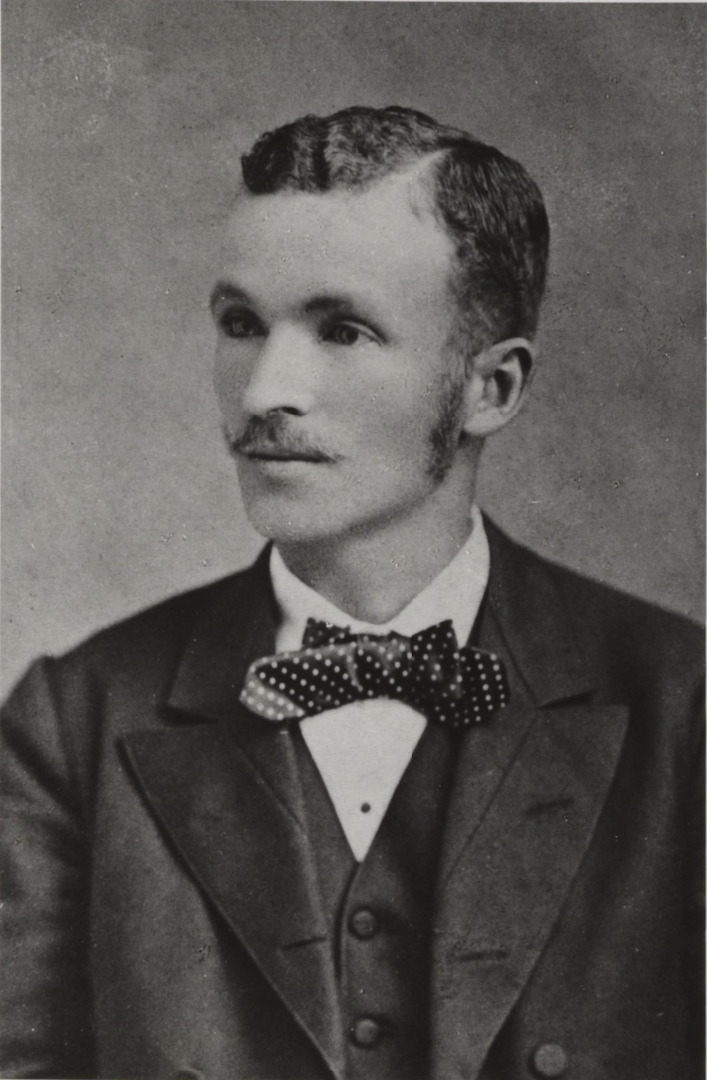

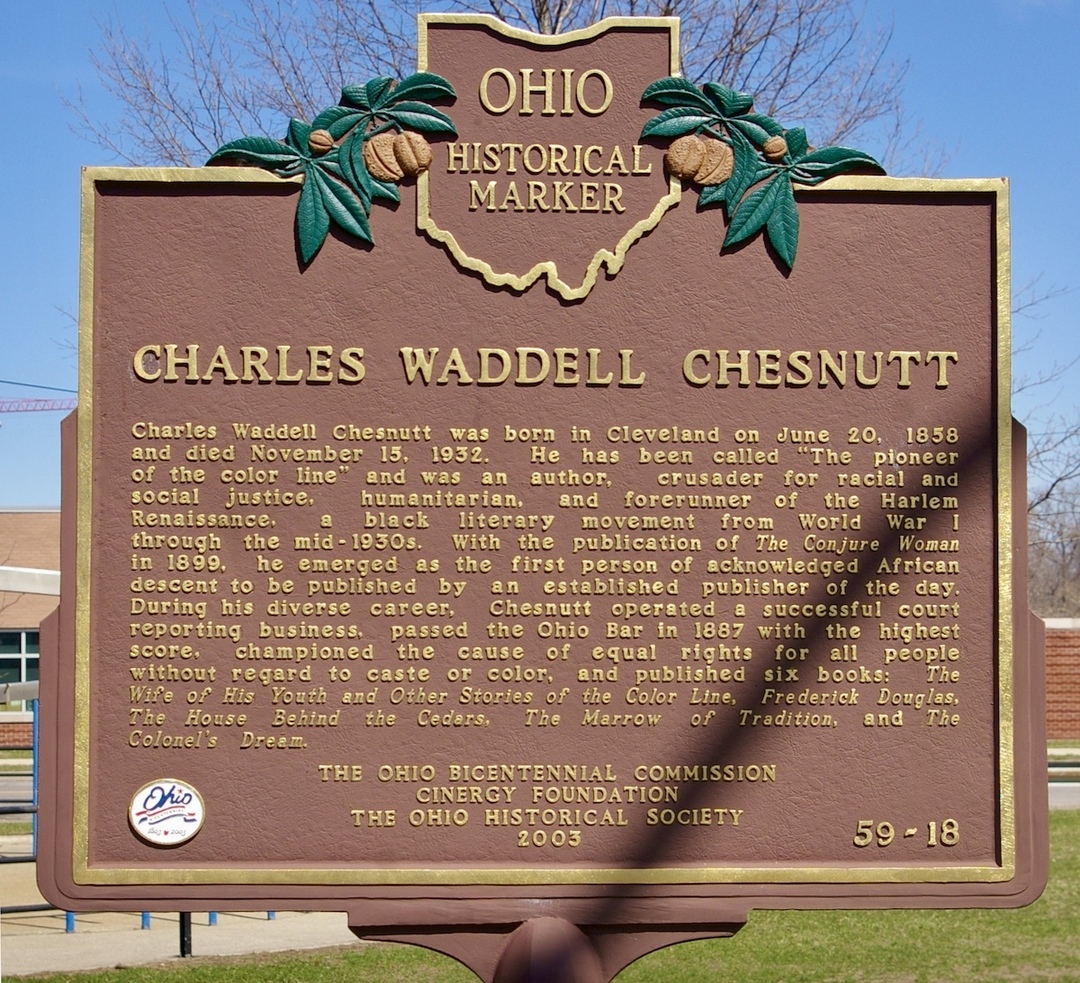

Charles Waddell Chesnutt was born in Cleveland, Ohio, on June 20, 1858. His parents, Andrew Jackson Chesnutt and Anna Marie Sampson, both of whom were biracial and free, had fled their hometown of Fayetteville, North Carolina in 1856, because the rights and liberties of free blacks living in the South were being severely curtailed in that decade which led up to America's Civil War. While Andrew Chesnutt initially headed to Indiana to live with an uncle there, Anna Sampson, her mother Chloe and her stepfather Moses Harris headed to Cleveland where, since the early 1850s, biracial families from North Carolina and other Southern states had been settling in an area of the city near Hudson (East 30th) Street, just south of what is today Central Avenue. There, these families—almost all of whom were headed by men who were carpenters, masons or other tradesmen—had formed a small but vibrant biracial community amid a white population composed mostly of German and Irish immigrants. Among the biracial families who had settled there earlier in the decade was the Cicero M. and Sarah Harris Richardson family. Cicero was a mason by trade who later became a "plasterer." Census and other public records suggest that Sarah was very likely a niece of Moses Harris.

Upon arriving in Cleveland, Moses Harris, who was a carpenter by trade, purchased (according to County tax records) a house on Hudson Street that was just a few houses down from the home of Cicero and Sarah Richardson. The following year, Andrew Chesnutt left Indiana, moved to Cleveland, married Anna Marie Sampson, and became a member of the Harris household. A year later, Charles Waddell Chesnutt was born. Except for parts of the years 1859 and 1860, when his parents temporarily relocated to Oberlin, Ohio, Charles Chesnutt spent the first eight years of his life growing up in his grandparents' house on Hudson Street. He likely played with both black and white children who lived nearby and, though there are no extant school records to confirm it, he likely attended, at least for several years, nearby Hudson Street School (later, Sterling School), an integrated public elementary school which was founded in 1859 and which stood on the southwest corner of Sibley (today, Carnegie) Avenue and Hudson, a mere quarter-mile walk from his home.

In these early years of his life in Cleveland, Charles Chesnutt would have also been witness to significant events in the neighborhood like the construction in 1864 of the original Shiloh Baptist Church on Hudson, just across the street from his grandparents' house. Undoubtedly, he would have thought it cool that his relative and neighbor, Cicero Richardson, a founder of that church, played a significant role in the ceremonial laying of the cornerstone for the new church by "the order of colored masons" on August 1st of that year. Moreover, in addition to the impact upon him of this event and his likely attendance at Hudson Street school, young Chesnutt would have likely also been impacted, or shaped, by the nearby Richardson family, which occasionally would expand with visits by Sarah Richardson's mother and siblings who had moved to Cleveland in the late 1850s, where they lived on Ohio Street (today, Carnegie Avenue near East 14th Street). He perhaps would have been most affected by visits from Sarah's brilliant younger brothers, Robert and Cicero Harris, who, in the early 1860s, were young adults. These brothers, just a few years later, would play an even greater role in the shaping of Charles Chesnutt.

In 1866, shortly after the end of the Civil War, Andrew Chesnutt, who had served in the Union Army, moved his family back to Fayetteville where his son Charles was enrolled in Howard School, a segregated school for black children. Robert Harris, the brother of Sarah Richardson, who had also moved back to Fayetteville after the war, served as the first principal of that school. Harris recognized Charles' talents as a student, and, when Charles graduated early from Howard School at the age of 14, Harris recommended him to his younger brother Cicero, a teacher at Peabody School in Charlotte, for an assistant teacher position. After teaching for three years in Charlotte under Cicero Harris' guidance, Charles was called back to Fayetteville in 1875 by Robert Harris to become a teacher at Howard school which had been converted into the State Normal School for training black teachers.

The next eight years were busy and significant ones for Charles Chesnutt. In 1877, he married fellow teacher, Susan Yu Perry, and by 1880 the two were parents of daughters Ethel and Helen. In that same year, principal Robert Harris, the man who had had enormous influence on the shaping of Charles Chesnutt, died suddenly. Chesnutt, at age 22, was picked to succeed him as principal of the State Normal School. The job paid well and was prestigious, but Chesnutt soon became dissatisfied with it. As a journal he kept from 1874 to 1882 noted, he had long fantasized of moving back to the North where he believed more opportunities, including the possibility of becoming a writer, awaited him.

So, in the spring of 1883, Charles Chesnutt resigned his position as principal of the school in Fayetteville and moved to New York. There he obtained a job as a reporter for Dow, Jones &. Co., but, after six months, he decided that Cleveland, where he had been born and had spent his early years, would be a better fit. He moved to Cleveland in the fall of that year, obtaining employment as a clerk in the accounting department of the newly organized Nickel Plate Railroad. The following year, his wife and children (including his son Edwin, born while Chesnutt was away in New York) joined him in Cleveland where they all moved into a rented house on Wilcutt Avenue (today, East 63rd Street) in the Central (today, Fairfax) neighborhood.

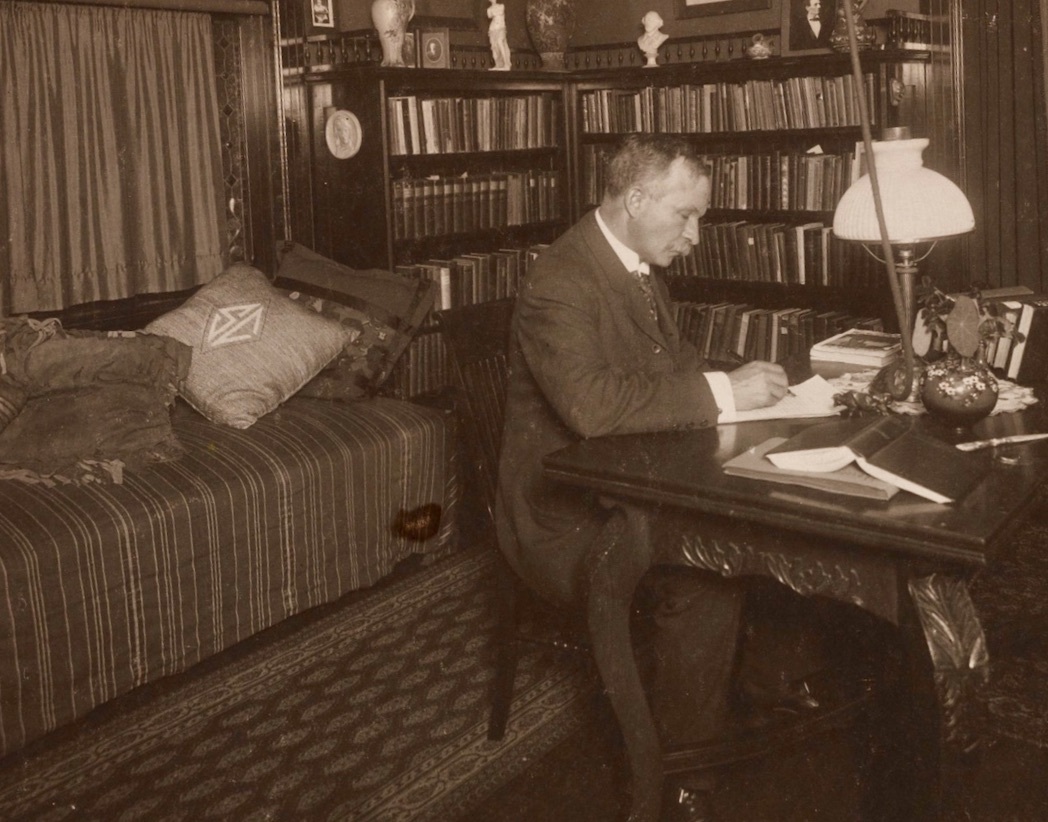

From 1883 to 1888, the Chesnutts rented several different houses in the Fairfax and Central neighborhoods. Finally, in 1888, they were able to purchase their first house, one that was located on Benton (East 73rd) Street, just south of Cedar Avenue, an upscale area of the Central neighborhood. In these early years that followied his return to Cleveland, Chesnutt was very busy with new employments, both as a stenographer (for which he had self-trained in North Carolina) and as an attorney—which he began practicing after "reading" the law and receiving the highest test score on the Ohio bar exam in 1887. Still, despite all this, he managed to find time in 1885 to turn his atttention to his dream job and in that year began writing for publication fictional stories about newly freed African Americans learning how to exercise their rights and live their lives in the Reconstruction South.

In December 1885, Charles Chesnutt's first story (as an adult writer) was published. Titled "Uncle Peter's House," it was about a former slave who tried to build a nice house for his family but failed during his lifetime because of the predatory sharecropping system instituted in the South in the post-Civil War period. The story was purchased by the McClure newspaper syndicate and appeared in a number of newspapers in the country, including the Cleveland Herald. Over the next two years, Chesnutt wrote a number of other stories about the post-War South that appeared in various newspapers and magazines. In 1887, his recognition as a writer reached new heights when his story, "The Goophered Grapevine" appeared in the nationally-known Atlantic Monthly.

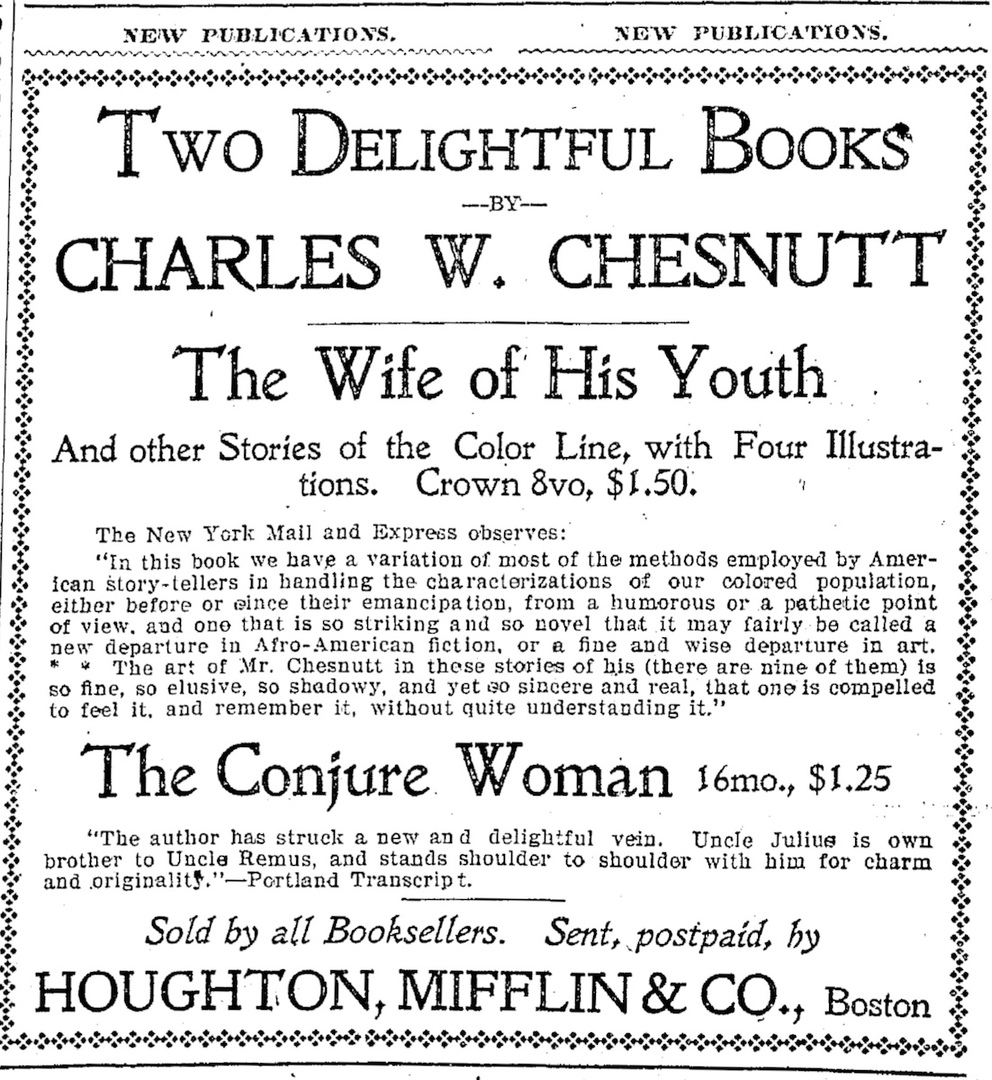

Thereafter, during the years 1887-1900, Chesnutt published forty-seven short stories in the Atlantic and other magazines and newspapers, some of these painting a graphic picture of life for newly freed slaves in the South and others showing how, even in the North, color mattered, albeit in different ways than in the South. In early 1899, two collections of his stories were published as books—one, The Wife of his Youth, consisting of stories about the "color line" in the North, and the other, The Conjure Woman, on stories of life for blacks in the post-war South. After these two books were published, William Dean Howell, an author himself and noted literary critic, praised Chesnutt, adding more glitter to his growing reputation as a great American writer.

After the successful debut of his first two books in 1899, Chesnutt sat down with his wife Susan and, after reviewing their family budget, they agreed that he could, for at least a two year period, close his attorney and stenographer offices and devote all of his time to his dream job of becoming a novelist. Over the course of the next two years, he wrote two novels that were published, The House Behind the Cedars (1900) and The Marrow of Tradition (1901). Each treated what was then a very sensitive subject—the first, intermarriage between a white man and a black woman, and the second—inspired by the Wilmington, North Carolina massacre of 1898—white supremacy and violence against Southern blacks who sought to exercise their rights as citizens. Neither book sold well and both were panned by critics for being too moralistic and by angry white Southerners who claimed they were filled with lies. Chesnutt, after seeing the poor book sales and the negative reviews, decided it was time to step back and reopen his offices as an attorney and stenographer, which he did in the new Williamson Building in downtown Cleveland in early 1902.

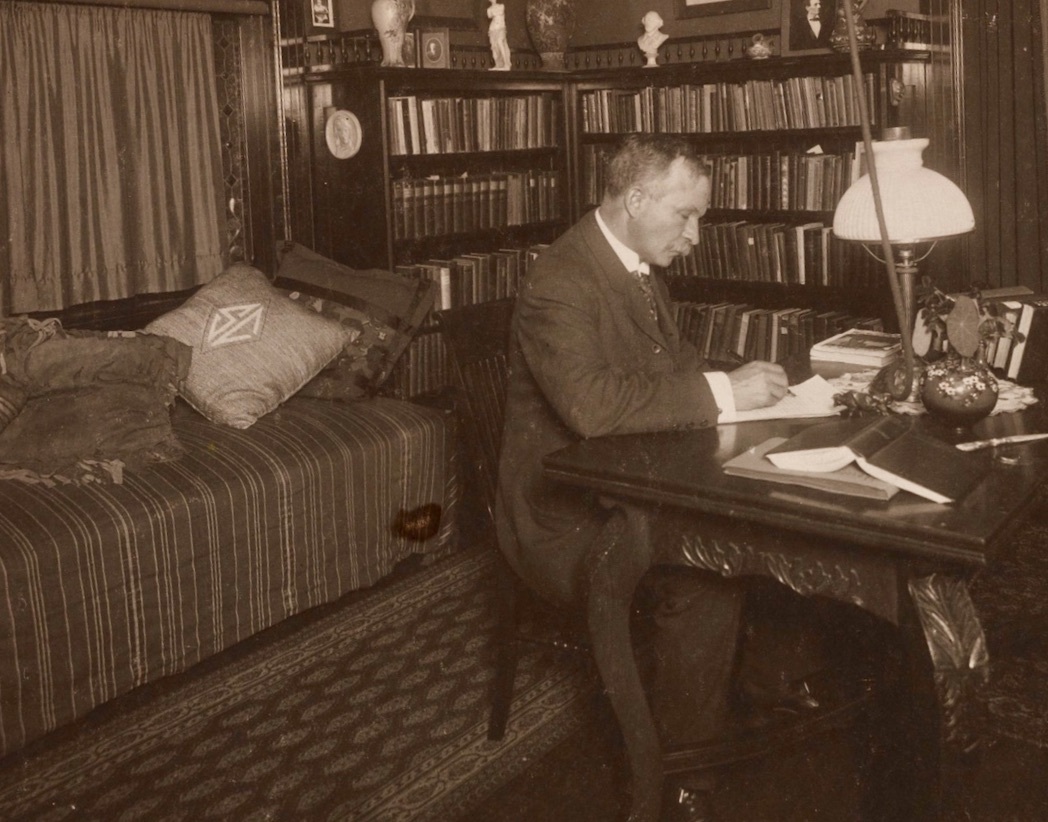

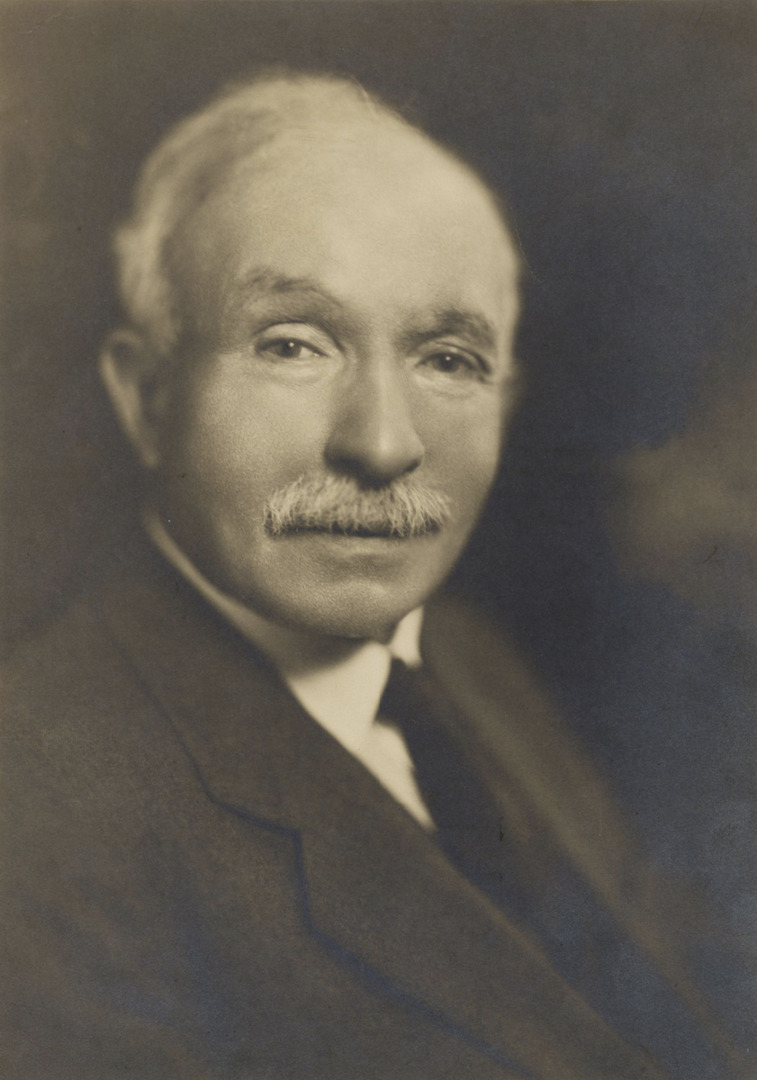

As noted at the beginning of this story, Charles Chesnutt's novel writing all but came to an end several years later in 1905 with the publishing of The Colonel's Dream. For Chesnutt himself and certainly for his family, it may not have been the worst result because, in addition to allowing him to write what he wanted about the race problem in America, and how he wanted to write it, he also now became free to pursue other important matters of both a personal and professional nature, including becoming a member of and participating in the Rowfant Club's literary work in Cleveland in 1910 (after the Club had rejected his initial membership application on account of his race in 1904); supporting the founding in 1915 of the Playhouse Settlement House, which later was renamed Karamu House; corresponding at length with other black intellectuals; traveling with his family across the United States and around the world; and lecturing, whenever called upon to do so, on the problems of America's "color line," always delivering thoughtful opinions on how it might best be finally erased in this country. And Charles W. Chestnut continued in such activities for the rest of his life.

When he died peacefully in his house on November 15, 1932, at the age of 74, his death was front page news for the Plain Dealer. All in all, despite the existence of racism in America and its impact upon him as a biracial man, Charles W. Chesnutt led a very enviable and comfortable life. He owned a grand house in an upscale, integrated neighborhood; he was respected by his peers, both white and black, in Cleveland—something that he had often dreamed about as a young black man growing to adulthood in Fayetteville, North Carolina; and he witnessed all of his children going to college and obtaining the degrees that had been denied to him. (Three of his children attended and graduated from Ivy League schools.) Perhaps then, it would be fair and not inappropriate to say that who suffered most from the premature ending of Chesnutt's career as a novelist was not he but we, the American public, who have been deprived ever since of reading the best novels that he never wrote.

Images