Greek Town

Onetime Heart of Cleveland's Eastern Mediterranean Communities

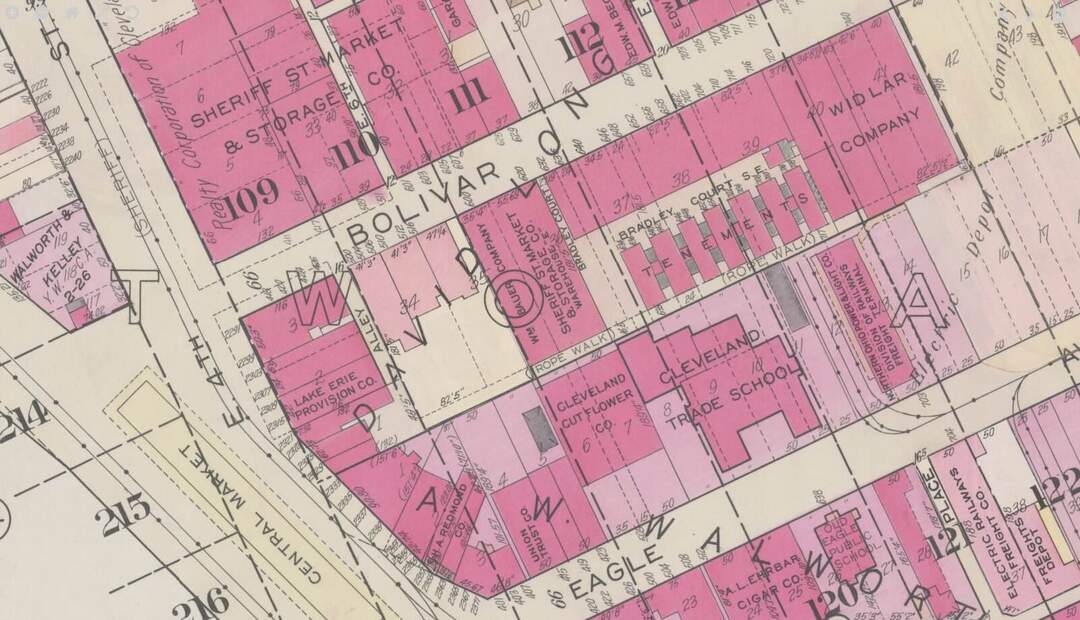

Cleveland’s Greek population, only 6 in 1890 and 42 ten years later, soared to near its peak of 5,000 before immigration restrictions in 1924 imposed low quotas for further newcomers from Greece and other eastern Mediterranean nations. A smaller but still sizable community of immigrants had also come from what are now Lebanon and Syria. So many Greeks settled in the Haymarket district around the Central Market that the enclave that some Clevelanders referred to this area as "Greek Town." Some Greeks worked as fruit and vegetable peddlers, others as day laborers or steelworkers. Over time, a number became storekeepers, bakers, and proprietors of coffee houses and wholesale import grocery houses selling everything from olives to dried devil fish. Bolivar Road emerged as the social center for Greeks, its numerous coffee houses serving as places where Greek men sipped coffee or tea, shared hookahs, gossiped, played cards, dominoes, or barbouth, and caught up on news from their homeland. Yet, even as Greek Town grew, it lost growing numbers of people to Tremont and neighborhoods along East 79th Street in the years after World War I.

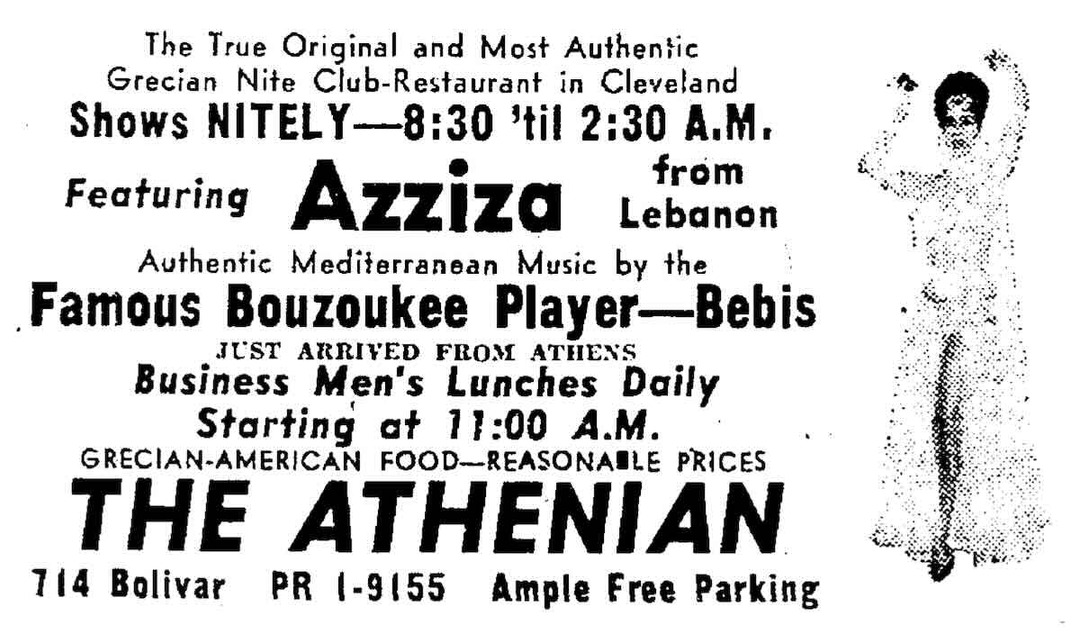

By the early 1940s, Plain Dealer columnist S. J. Kelly lamented that he “found Bolivar Road sadly depleted of its Greek. It is, in fact, a modern business thoroughfare and most of its classic residents are scattered over the city.” In the postwar years, as so many Clevelanders departed for the suburbs, remnants of ethnic communities beckoned as “old and colorful” anomalies in a downtown increasingly dominated by office towers and parking garages. As Bolivar Road transitioned from a complete neighborhood to the central business district for Greek, Lebanese, Syrian, and Palestinian populations that were now spread across the metropolitan area, it also gained greater popularity beyond these communities. A succession of "Grecian-American" restaurant-clubs at 714 Bolivar — The Athenian, Grecian Nites, and Never On Sunday — enticed patrons with belly dancers and bouzouki music. Middle East Restaurant, opening in 1962, introduced many Clevelanders to Middle Eastern cuisine. The restaurant’s proprietor, Edward Khouri, a native of Aramoun, a village near Beirut, built a loyal clientele with inexpensive, authentic dishes prepared and served by Josephine Abraham, also Lebanese. As Abraham later recalled, pita and hummus were so exotic to many customers when she started at the restaurant that she had to instruct them on how to use pita to eat hummus; “It was like feeding babies,” she quipped.

In 1973, the Greek and Middle Eastern businesses on Bolivar Road, along with the L&K Hotel, a single-room-occupancy hotel for “down-on-their-luck men,” fell to the wrecking ball to make way for a parking lot, which was later replaced with a garage for Progressive Field and Rocket Mortgage FieldHouse. Plain Dealer columnist George Condon echoed S. J. Kelly’s lament of three decades before, complaining that “downtown is diminished again.” While the Middle East Restaurant and Shiekh Grocery were able to find space in and next to the Carter Manor (formerly the Hotel Carter), other businesses dispersed. Today there is no sign of the Greek, Lebanese, and Syrian enclave on Bolivar. Greek culture revolves more around churches such as Tremont’s Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church. However, on nearby Carnegie Avenue, St. Maron Church and Aladdin’s Bakery and Market still offer visible reminders of where Cleveland’s Middle Eastern communities got their start.

Images