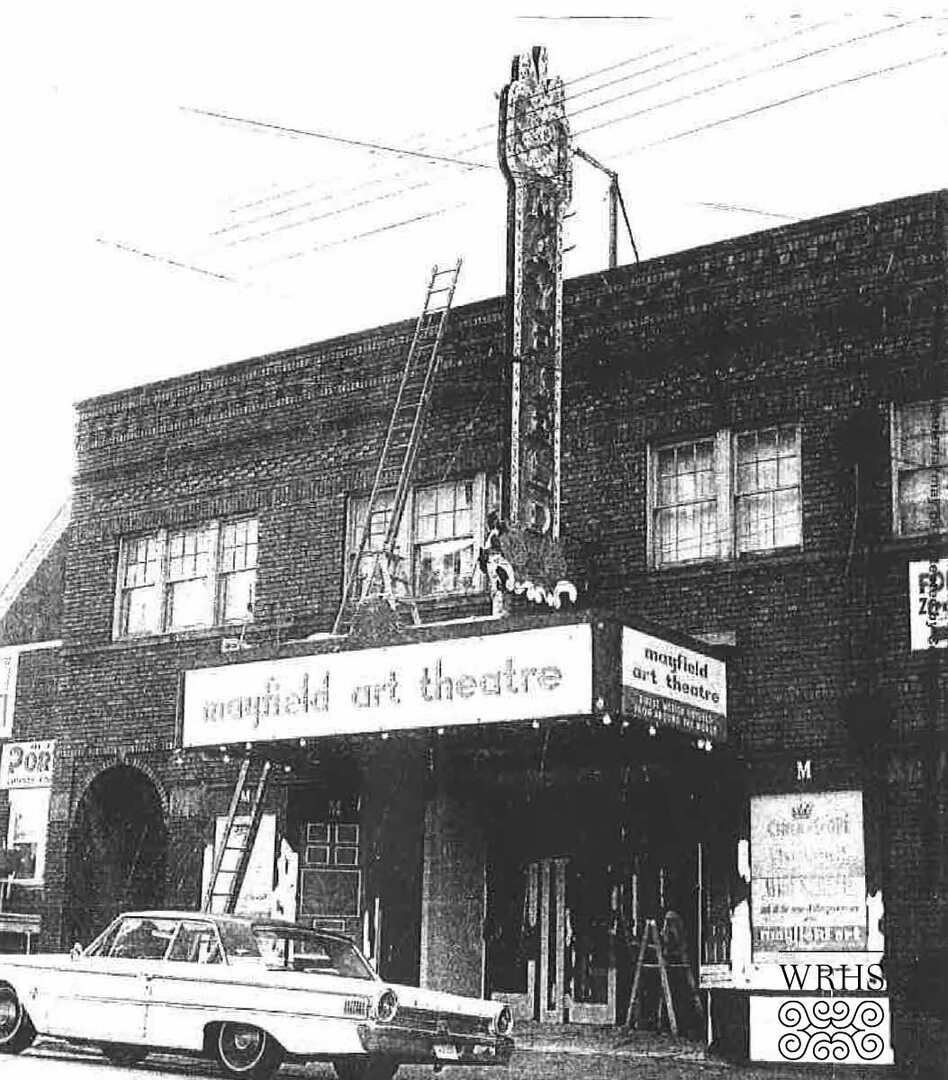

Walking or driving through Little Italy, how many of us have wondered, “Why doesn't someone reopen or repurpose that old theater?” It’s a reasonable question despite the obvious challenges (cost, parking, safety, etc.). After all, the Mayfield Theater—a.k.a., the Mayfield Art Theatre, the Old Mayfield Theater, and the New Mayfield Repertory Cinema—has been shuttered for close to 40 years.

The “Old Mayfield” moniker is particularly resonant for those passersby of the Baby Boomer generation whose moviegoing journeys to 12300 Mayfield Road were in the late 1960s. That’s when this now-unassuming hole in the wall briefly became the go-to spot for silent films, silver screen classics, and revivals. For a time, “old was the new new.”

That incarnation (the theater's third) also may have struck a chord simply because the place exuded “old.” Original Arts and Crafts–style glass transoms. Crown molding. Time-worn terrazzo floors. Tickets were issued from a closet-like opening in the entryway, after which visitors would enter a gloomy and cramped low-ceilinged lobby. Directly above, a tiny projection booth could be accessed only via a metal ladder. By the late ’60s the theater’s original seats (some allegedly taken from the Euclid Avenue Opera House) were gone, but their rickety replacements were a perfect musty accompaniment to the showing of a 1920s or ’30s movie.

The first of the Mayfield Theater’s many lives began in 1923, when Michele Mastandrea, an Italian immigrant, built the two-story brick building with a theater on the first floor and a large apartment on the second. Mastandrea had previously operated a dry goods store on that same parcel. Before that he worked as a shoe salesman in a shop on the current site of Maxi’s Bistro. Mastandrea and his wife Christina lived in a small house behind the theater (fronting Fairview Court) until they moved to the new building’s second floor quarters in 1929. They operated the theater and remained in the spacious eight-room apartment until their deaths in 1955 and 1958, respectively.

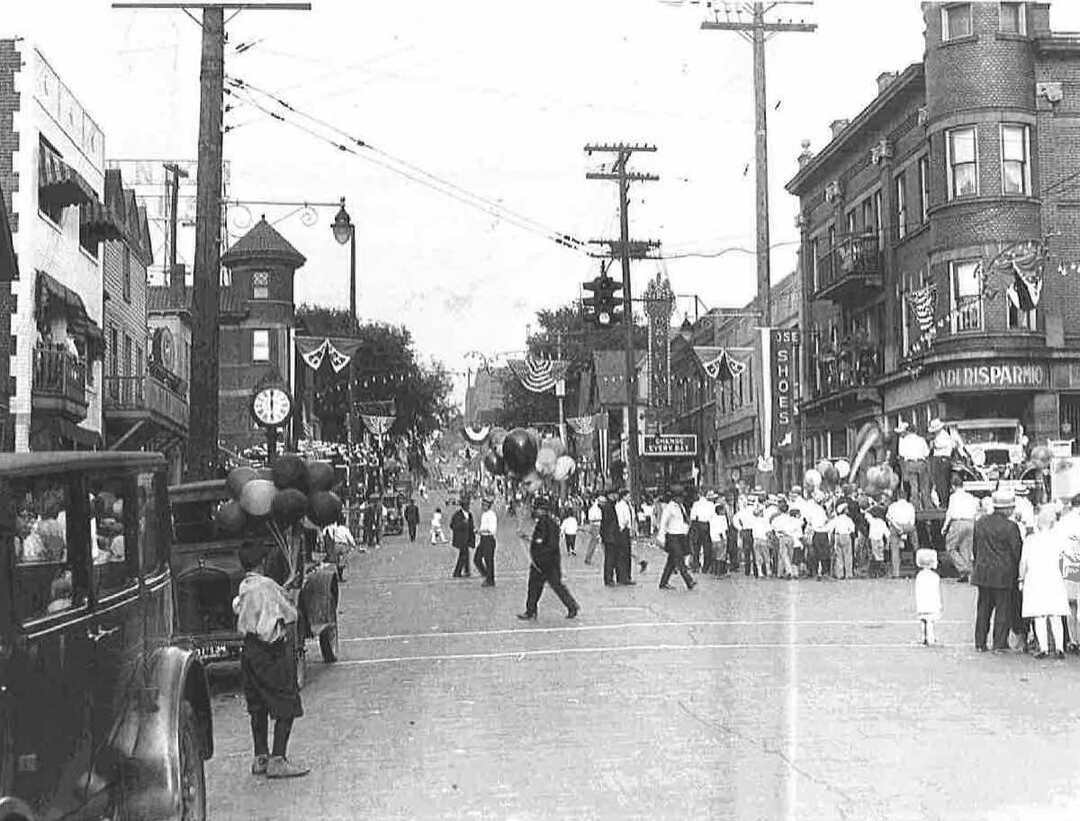

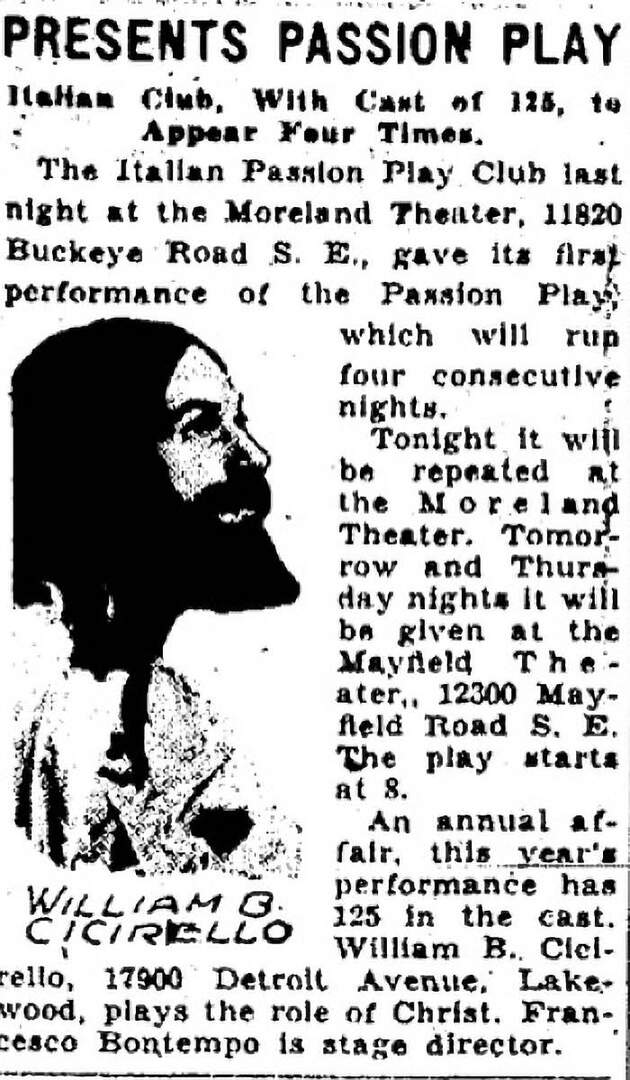

The Mayfield wasn’t Little Italy’s first theater. The Venice, which opened around 1915, was a converted storefront at 12016 Mayfield Road, current site of the Little Italy Visitor Center at Random and Mayfield. The Roma Theater, a few years older than the Venice, staged live performances and possibly short films. It was located directly across Random Road from the Venice, where Tony Brush Park now stands. Both venues closed more-or-less concurrently with the opening of the Mayfield, which continued to be the only theater in Little Italy throughout its 32-year run. Mastandrea’s offerings included Italian-language and second-run Hollywood movies, as well as occasional live performances of Italian plays. As the neighborhood’s largest gathering space, the Mayfield also hosted community meetings and lectures, benefit performances (e.g., for Holy Rosary Church), Feast of the Assumption and Columbus Day celebrations, and political gatherings. In November 1930—the night before the national election—Ohio senate candidates debated at the Mayfield.

Michele Mastandrea died in August 1955 and the theater closed. In January 1959, it reopened as the Mayfield Art Theater, part of a national chain of art movie houses. Veteran managers Jack Silverthorne and Jack Lewis upgraded the marquee, interior, and projection equipment, and installed a new CinemaScope (super-wide) screen. The two Jacks showed first-run foreign films, as well as domestic comedies, dramas, and documentaries. Rod R. Mastandrea, a Cleveland attorney and son of Michele Mastandrea, assumed control in September 1959, a tenure that ended that December when the curtain came down again, save for a very brief attempt at live theater in 1961.

Amid the tumult of 1968, some Clevelanders may have been particularly primed for nostalgia. Thus emerged the space’s third reincarnation: the Old Mayfield, which the Plain Dealer’s George Barmann christened “Cleveland’s first silent movie house since the silent movie houses.” Blood and Sand with Rudolph Valentino kicked things off on October 3, 1968. Forthcoming attractions included The Gold Rush with Charlie Chaplin, Way Down East with Lillian Gish, Arizona Wooing with Tom Mix, The Hunchback of Notre Dame with Lon Chaney, and The Mark of Zorro with Douglas Fairbanks.

The Old Mayfield's emergence wasn't driven by movie men. Instead, the rescuers were Sam Guarino, owner of Guarino’s restaurant and Hank Schulie of the Golden Bowl. After forming the Itlo Development Corporation (Itlo stood for Italian Little Italy Organization), the two restaurateurs cleaned the place up, hired a pianist, and installed a beer and champagne bar in a corner of the lobby. Alas, their enthusiasm was not enough to overcome the area’s incessant parking problems as well as the race-related tensions that typified the time and the neighborhood, and the theater closed in October 1969. It reopened briefly in January 1970 with a spate of Marx Brothers and W.C. Fields movies, but lapsed back into sleep by late spring.

After four years, the theater was resurrected for the last time by an English and drama professor and cinephile named Sheldon Wigod. Dubbing his new movie house the New Mayfield Repertory Cinema, he stuck with classic movies but interspersed them with foreign films—from Flynn to Fellini. Wigod brought a personal—and personable—touch to the business, introducing each film prior to its showing. It was during Wigod’s tenure that the building was designated a Cleveland Landmark.

Wigod’s labor of love did better than most; the New Mayfield Repertory Cinema stayed awake until 1985 but has been vacant ever since. However, it did receive a spot on the National Register of Historic Places in 2013. And why hasn’t there been another reawakening? We periodically see vague hints—a cleanup here, a supply truck there—but specifics are few and barriers are many. Parking challenges are clearly a major hurdle. However, it seems likely that adhering to modern fire and safety codes might play a part, as could the high cost associated with converting to a digital film format or turning the space into something other than a theater.

Images