"It is seldom that an entire neighborhood packs its trunks and moves in a body," wrote The Architectural Exhibitor in April of 1929 about a group of neighbors living around Hessler Road. The enclave of creative professionals planned to move into a community of their design, giving way to a historic development that bridges Cleveland and Cleveland Heights and urban and suburban living.

Locally known as Belgian Village, Fairhill Road Village was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1990. Originally called Fairmount Place before the change of the development’s frontage road's name from Fairmount Road to Fairhill Road, the single-family homes combine detached and semi-detached dwellings. Today, thirteen homes comprise the Fairhill Road Village Historic District; five two-family semi-detached units built over the winter between 1929 and 1930 and three detached homes built intermittently in 1930, 1933, and 1971.

Fairhill recalls other planned communities built around the same time, notably Mayfair Lane in Buffalo, Sessions Village in Columbus, and the French Village in Philadelphia. All share the use of uniform architecture in a historic-revival style and semi-detached layout. Fairhill’s use of an unusually natural setting so close to an urban center allows it to be an exemplary model of this mode of building.

Standing on the abandoned debris created in the 1915 construction of the Fairmount Reservoir, Fairhill literally straddles the divide between urban and suburban by being built over the municipal boundary between Cleveland and Cleveland Heights. Architecturally Fairhill blends into its neighboring communities through historical revival architecture that evokes a common European heritage, a facet of suburban living. The development utilizes a style reflective of the Cotswold Hills District of England. The homes favor white varied stone and stucco with multiple gables and various recesses in the façade, creating the overall effect of an English hamlet appearing out of the forest.

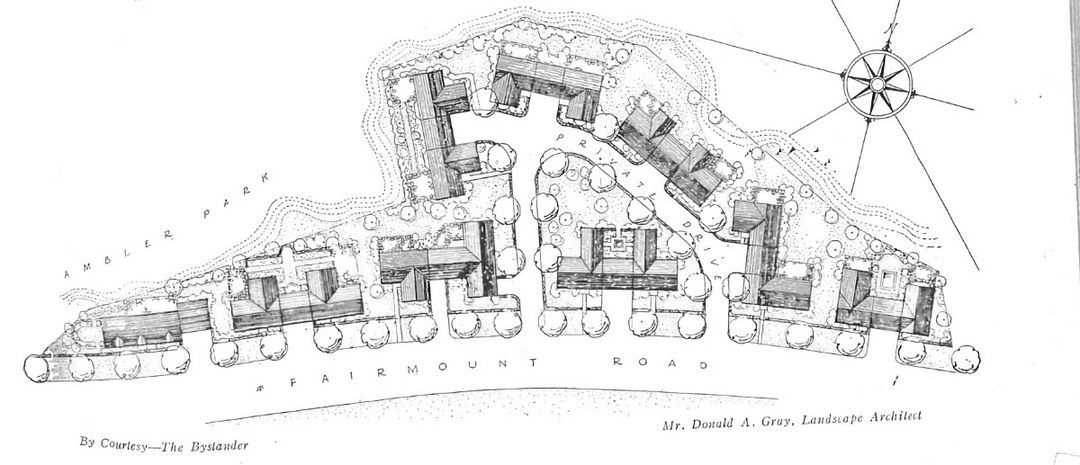

The combination of shared and private space is central to Fairhill’s makeup. Originally planned as seventeen semi-detached homes by architect Antonio DiNardo, the eleven houses share a single drive with the dwellings facing a private park directly off Fairhill Road for shared use of the residents. The semi-detached units connect via their respective garages while service rooms above allow a more insular living space that looks onto private terraced gardens built at the edge of a ravine running through Ambler Park.

Landscape architect A. Donald Gray drove Fairhill’s development from conception to completion. Before moving to Cleveland, in 1920, Gray worked for The Olmsted Brothers landscape architecture firm under Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. Gray’s profession and his connections to the lauded firm show throughout Fairhill’s design.

The use of gardening to accentuate a site’s beauty and create natural boundaries was a key principle in Olmsted’s work and reflects in Fairhill’s balanced relationship between architecture and landscape. Each private terrace uses flower beds sparingly in order not to distract attention from the natural landscape. Decorative pools mirror the Doan Brook at the bottom of the ravine while simultaneously attracting birds into the garden. The additional planting of trees and shrubs at the front of the development creates a natural boundary between the homes and the roadway leading to the city.

The construction of Fairhill Road Village coincided with a culmination of development in suburban Cleveland before the Great Depression. By the end of the 1920s, Cleveland’s population had reached 900,000. The completion of the Union Terminal complex would mark Cleveland as a great American industrial center, with one of the tallest buildings in the country serving as a grand focal point for commuters going to and from their rapidly expanding suburban neighborhoods. Between 1919 and 1929 an average of 300 new homes were built annually in Shaker Heights. Literature and pamphlets were used like propaganda championing the single-family house on a large site and demonizing living close to vestiges of the city like factories, apartments, and minorities.

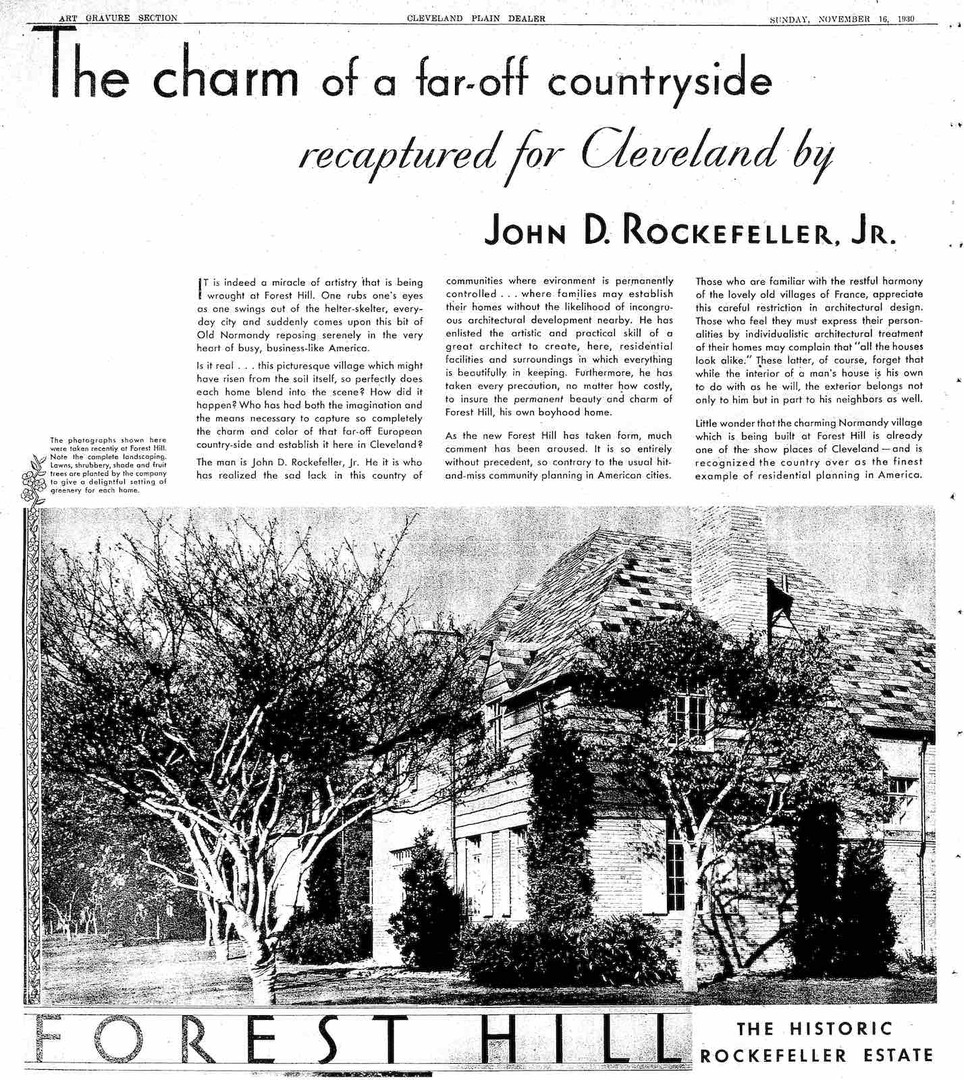

Nearby, John D. Rockefeller Jr. was developing the site of his family’s former country estate, Forest Hill, into another residential community. To promote his development, he mounted a large-scale advertising campaign in local papers that played on his bucolic childhood and promised to “revolutionize American standards of home construction” and ensure that “your neighbors are inevitably people of tastes in common with yours.”

In contrast to these commercial enterprises, Fairhill Road Village echoes the communal aspects of the Garden City Movement. Spearheaded by urban theorist Ebenezer Howard’s Garden Cities of To-Morrow, the Garden City attempted to alleviate the congestion of urban life by creating small, self-contained, and interconnected communities that would give residents access to the benefits of both urban and rural living while also making them stakeholders through communal ownership. Unlike Shaker Heights and Forest Hill, profit was not Fairhill’s concern. It started as a collaboration between creative professionals living on Hessler Road who wanted to move away from the frenzy of Cleveland towards the tranquility of Cleveland Heights while maintaining the cultural sophistication of urban life. Fairhill incorporated many of the ideas championed by the Garden City Movement through shared ownership, green space, and limited size.

The Fairmount Development Group, comprised of future residents of Fairhill, was formed to purchase and subdivide the property into individual lots. The company’s mission statement clearly outlined its objective “to get a group of interesting people to build semi-detached houses in the same style of architecture, to build these houses on small areas of land…” Through a co-op model, the residents of Fairhill pooled resources to procure the land on which to build their homes. This communal approach was unusual as shown by A. Donald Gray’s letter to architect H. O. Fullerton that showed the committee in charge of securing the loan at Cleveland Trust for the development of Fairhill was “skeptical” because the proposition “was a new idea to them.”

Inadequate finances and a lack of interested parties created an obstacle to the construction of Fairhill. To fill the appropriate number of building plots, the Fairmount Development Group members were enlisted to find interested people within their network. One Fairhill planner, J. T. Seavers, told Gray, “I’m putting it up to every family to get one more pronto, and we will not only be done but have a waiting list.”

A sense of urgency pervaded the building of Fairhill that correlated with the beginning of the Great Depression. Cleveland Plain Dealer business columnist, and original resident, John W. Love wrote on October 24, 1929, about his unease in Cleveland’s labor conditions amid a large building project. Love cited labor’s stable relationship with “the Vans” (Van Sweringen brothers) during the five-year construction of the Terminal complex as long as they didn’t “rock the canoe,” but that those agreements would end in the spring, and he urged the building to be completed before March 31 to avoid a potential strike. A week later, on Black Tuesday, he used the urgency of the telegram to communicate what must have been a growing sense of dread, writing, “Financial conditions [are] so extremely ominous that I doubt we ought to proceed with construction except with best possible guarantees of money and stability of contractor.” By April 1930, ten of the seventeen planned homes were completed in the spirit of DiNardo’s original plans if not in size.

The Great Depression crippled neighboring developments like Shaker Heights and Forest Hill. Donald Gray saw Fairhill’s innovative collaboration amongst its residents as a potential benefit in residential development during the Depression. In a letter to The Ladies Home Journal, Gray wrote of how the residents were able to lower the cost of building by sharing building materials because of Fairhill’s uniform style as well as sharing the expense of an architect. In a letter to House Beautiful Magazine, Gray stressed Fairhill’s merits, writing, “It seems to me that in these days of economy that the scheme has a great deal of interest to the general reader.” The letters show Gray’s belief in Fairhill’s social and economic benefits while demonstrating its adaptability to changing times.

The planned community allowed refuge for Cleveland’s white population to create enclaves amongst themselves. Fairhill’s co-op model and design reflected the intention to innovate in habitation, but not immune to the self-selective nativist sentiments prevalent in the 1920s. Fairhill’s formation of The Fairmount Road Association allowed members of the community to retain the social control that The Architectural Exhibitor alluded to in writing, “In every community, there are certain sections and sometimes individual streets to which people of kindred tastes and habits naturally gravitate.” To live, build, or sell in the development required the approval of three-fourths of the Association's trustees—a trustee was either the owner of a home or their spouse—allowing the residents to foster a social homogeneity in line with its times. Fairhill never fulfilled its objective as outlined in The Architectural Exhibitor of moving the original group of Hessler Road residents into a community of their design. Nevertheless, Fairhill proved to be the cross-section of creative, cultured, and professional people reflective of its origination on Hessler Road including Russell and Rowena Jelliffe, founders of Karamu House, retired movie star May Alison, and aforementioned John Love and A. Donald Gray.

Images