Saint Sava Serbian Orthodox Cathedral

A Community and a Church Divided and Reunited

The newly constructed St. Sava Cathedral was the centerpiece of the Serbian and Eastern Orthodox community. It boasted a spacious area for worship, welcoming crowds on Sundays and festive holidays, and featured a large hall for gatherings like weddings, festivals, and communal dinners. Its establishment filled a void that the Serbian community felt with their previous church on East 36th Street. Yet, the political upheavals in Yugoslavia soon impacted this harmonious community, leading to the existence of two identically named churches in close proximity. How did this happen? Read on.

Cleveland’s Serbian history traces back to 1893 when Lazar Krivokapic, the first Serb-Montenegrin, arrived. Unlike many other early Serbian immigrants who worked in low-wage, industrial jobs, Krivokapic was a highly educated diplomat stationed in Constantinople, then part of the Ottoman Empire. The Serbian population in Cleveland steadily increased, reaching over 1,000 by 1914. Most of these immigrants lived in extended family units called Zadruge, housing up to sixty members each. The transition to American family structures was often jarring, especially for those from rural Serbia who had little exposure to industrial work environments. Their residential choices were influenced by work, leading to settlements in areas close to their workplaces.

World War I brought devastation to Serbia, claiming approximately 3.1 million lives. Answering the call to defend their homeland, between 400 and 500 Cleveland-based Serbs joined the war effort. The local paper, The Plain Dealer, highlighted the potential for an exodus that could disrupt the city’s industrial and commercial activities. It was important to ensure that southern Slavs, who primarily worked in the industrial sector, were not coerced into striking during the war. Today, the St. Sava Cathedral in Parma displays a plaque honoring those who fought and died in World War I.

As Eastern Orthodox Christians, Serbians’ lives are intertwined with the Church calendar. The absence of a designated church building until 1919, however, left early Serbian settlers without a spiritual home. Instead, they held worship services and celebrations in rental halls and cultural societies. The community eventually purchased a German Lutheran church on East 36th Street in 1919, which became the first St. Sava in Cleveland.

After World War II, another wave of immigration from Yugoslavia to Cleveland ensued. New immigrants, largely comprised of war prisoners, Chetniks loyal to the Serbian monarchy and Church, and those seeking economic opportunities, settled south in Parma and Seven Hills. They chose not to return to Yugoslavia, which had transformed into a communist state. However, the increased influx of new Serbian immigrants strained the resources of the small church on East 36th Street, leading to the purchase of land for a new church in Parma.

In 1963, amid financial problems, disputes arose within the church community. A division was formed when the Holy Synod of Belgrade, under Patriarch German’s leadership, removed Bishop Dionisije as the sole leader of the American-Canadian diocese and created three new dioceses. Some parishioners believed this move indicated communist infiltration of the Serbian Orthodox Church. Two factions emerged, one siding with Father Branko Skaljac and Belgrade, and the other with Bishop Dionisije and Father Branko Kusonjic. Both factions laid claim to the newly constructed St. Sava and its properties.

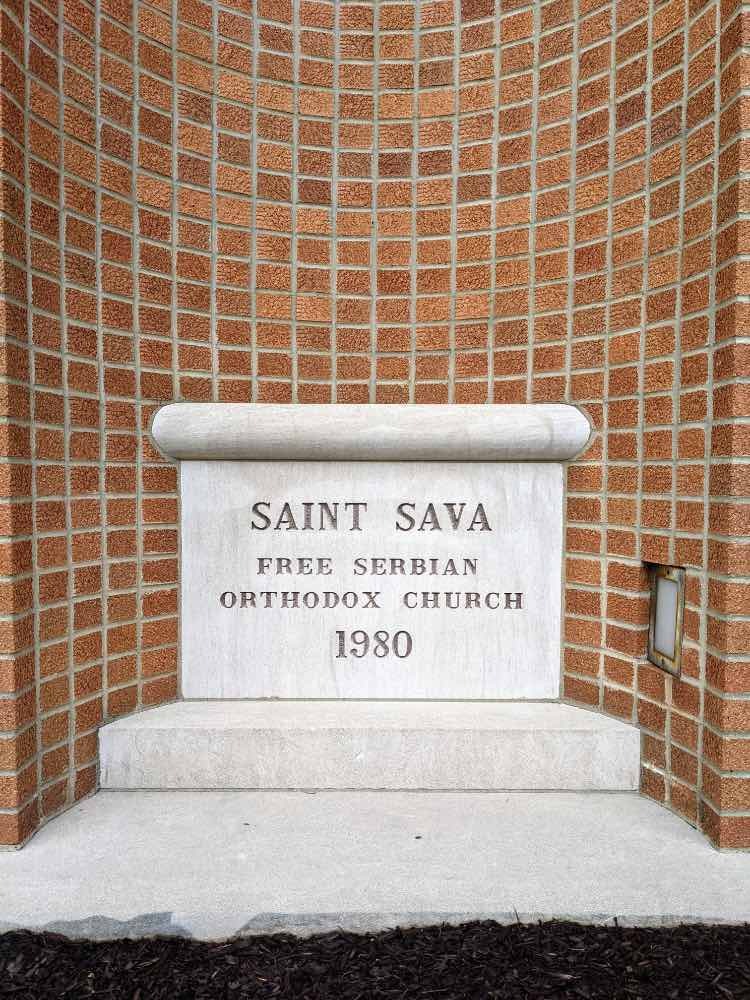

After twelve years of protracted legal battles, the pro-Belgrade faction was granted St. Sava and half the lot in 1975, while the faction loyal to Bishop Dionisije received the other half and the picnic grounds in Broadview Heights. In 1980, the Bishop Dionisije faction, now recognized as the Free Serbian Orthodox Church, completed another St. Sava in Broadview Heights. It was not until Patriarch Pavle’s intervention in 1992 that the dispute was finally resolved. Today, members from both churches interact during events, religious services, picnics, and soccer tournaments, reflecting a harmony long awaited.

Images