In the early 20th century, many African Americans sought refuge in northern cities from the tyranny and violence of the Jim Crow South. For those participating in this Great Migration, a city such as Cleveland seemed a logical choice, with the promise of economic and social benefits, not least a growing African American population to provide a sense of community. In the midst of this influx, African Americans became increasingly channeled into the crowded Cedar-Central neighborhood. Churches, music halls, and even beauty parlors in the community all played a signal role in providing places where black newcomers could come together. The Wilkins School of Cosmetology was one such place that reflected the mixture of entrepreneurship and social service that helped make Cedar-Central a vital community.

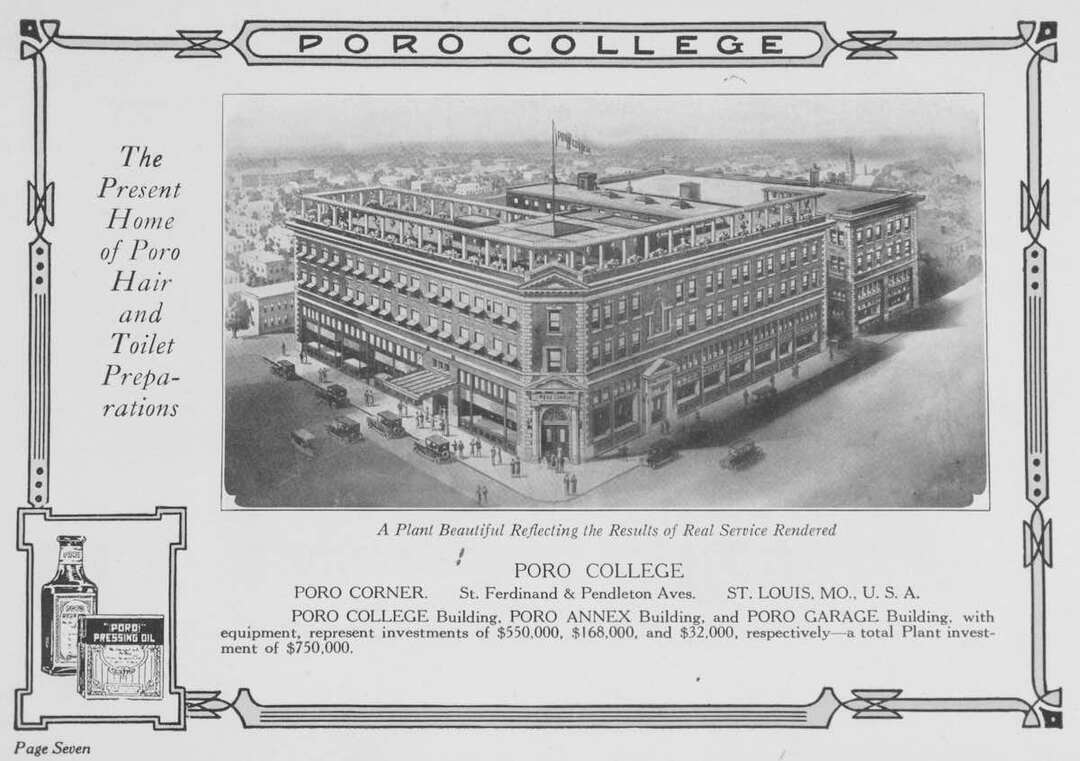

The school's founder Edith Wilkins, the eldest of twelve children, was born in 1893 in a white-washed cabin of the farm of her grandparents in Plumville, Arkansas. After graduating from the Poro College of Cosmetology in St. Louis, she moved to Cleveland with her husband George, a South Carolina-born fireman for White Sewing Machine Co., and two daughters in 1918. After waiting tables at Halle Bros. department store, Wilkins soon established a career as a beautician when she opened her first salon at 3812 Scovill Avenue.

On the advice of friends, Wilkins became a cosmetology educator when she took over an existing beauty school located on the main floor of the Phillis Wheatley building on Cedar Avenue at East 46th Street. The Phillis Wheatley Association provided support and a safe place to live for young, unmarried African American women newly arrived from the South. Although this location seemed to be a fitting spot for the parlor, the business's soaring popularity necessitated an expansion that simply was not possible in the Phillis Wheatley building. Wilkins ultimately purchased her own house on East 46th just north of Cedar Avenue in early 1936. Following renovation, it officially opened as the Wilkins School of Cosmetology.

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s the Wilkins School of Cosmetology grew further. Wilkins educated students from not only the U.S., but also Canada, Cuba, Africa, and the Caribbean. The school also provided African Americans, especially women, a space in their community where they could connect and grow together. Beauty parlors served as important social spaces for both women and men in the African American community. They were safe spaces, away from the hostilities sometimes faced in the white world around them, which explains why the Wilkins School was regularly featured in the Negro Motorists' Green Book. Moreover, the school gave black women a sense of empowerment while teaching them skills to become financially independent. Wilkins often allowed new students to study tuition-free and in many cases would even cover their room and board until they could pay their own way. Reflective of the school's communitarian nature, Edith Wilkins hosted many social and professional groups at the school such as the Jewelites Social Club, the Venus Club, the Economical Art Club, and the Business and Professional Women's Club. During the depression and war decades the school maintained continuous enrollment. Many of its graduates either found work in other salons, came back to work for the school, or in some instances pursued higher education.

By the 1950s and 1960s the Civil Rights movement gained steam in Cleveland. Wilkins and the School of Cosmetology, from the beginning, had supported other African American business endeavors in Cleveland. These included not only other salons and beauty parlors, but also the Cleveland Call and Post newspaper, and the Eliza Bryant Home, formerly known as The Cleveland Home for Aged Colored People. Wilkins also was able to get the school into the national and even international spotlight through her political work striving for the rights of African Americans and women. As a representative of the Cleveland Council of Negro Women, Wilkins had the opportunity to travel to many countries, including to Belgium to attend the World Brotherhood of Christians and Jews. Wilkins is also considered one of the founding members of the Ohio Association of Beauticians.

After turning over administration of the school to her daughter Lucille Francis in 1974, Wilkins remained active in the school and in the community. Her daughter continued to run the school in the same way as her mother before her. She maintained its reputation of being a modern, technologically advanced institution while also keeping its programs widely publicized in the press. During her tenure, the graduating classes reached record numbers, and the institution celebrated its thirty-fifth commencement exercise. Lucille, like her mother also had a strong sense of what the School of Cosmetology meant to the community, and frequently asked public figures in the African American community to come and give lectures, as well as to speak at commencement exercises.

After Edith Wilkins's passing in 1988, the School of Cosmetology started to lose its popularity. Newspaper articles and advertisements slowly decreased, but the School still lived on through the memorialization of Wilkins. She is memorialized at the Eliza Bryant Home hall of fame, as well as the St. James A.M.E. Church in honor of her service to the church's Women’s Day. Although it is unclear when the building at 2112 East 46th Street was demolished, records indicate that the land on which it stood was given to the Lane Metro Christian Methodist Episcopal Church in 1997, with the lot remaining empty today.

Images