“Entering Apartheid Shaker: Home of Barricades” was the message commuters read as they drove under a large banner while entering Shaker Heights along the Cleveland border in September of 1990. The banner was put up by Cleveland city councilman Charles Patton, who stated that “if the Berlin Wall can come down, so can the Shaker barricades.” His frustration was fueled by years of negotiation leading nowhere regarding the traffic barriers installed along the Cleveland and Shaker Heights border fourteen years prior.

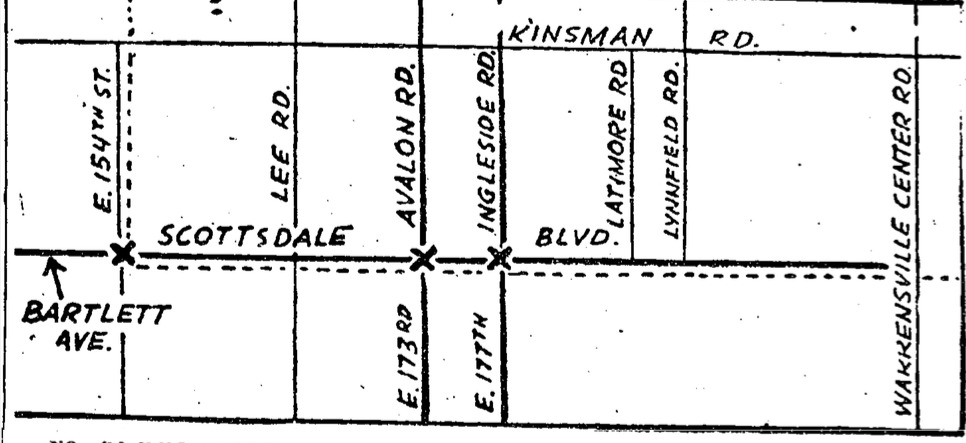

In 1976, temporary traffic barrels were placed on six streets in the Lomond neighborhood of Shaker Heights: Scottsdale Boulevard at Lee, Avalon, Ingleside, and Warrensville Center Roads; Rawnsdale Road at Lomond Boulevard; and Kenyon Road just east of Lee Road. Some of these blocked Cleveland motorists from entering Shaker streets, creating overflow in the adjacent neighborhoods of Warrensville Heights and Lee-Harvard. Shaker Heights declared that the barriers were put up at the request of residents to prevent accidents and traffic jams. Few traffic accidents or backups were recorded in newspapers from this time, but traffic influx was a problem many suburbs faced during the increase of suburban migration during the twentieth century. By the time the barriers were installed, the suburban fringe that makes up the Cleveland-Shaker border had become predominantly African American as a result of black migration into the suburbs during the 1960s. Therefore, the roadblocks along or near the border were perceived as a racially driven decision by many Cleveland residents, some even decrying “the Berlin Wall for black people.”

The 1976 barricades were not the first racially charged traffic decision made by Shaker Heights. As early as 1959, Shaker changed the name of Kinsman Road to Chagrin Boulevard, beginning at the border of the suburb. The name was changed after the murder of a white businessman by three African American youths on Kinsman, about a mile west of the Shaker city limits. Merchants, business owners, and community members petitioned to have the name changed. Some residents even stated they were embarrassed to give their addresses while shopping because clerks would assume they “lived near the murder.”

That same year, Shaker Heights politicians were discussing the use of traffic diverters in their attempt to separate the wealthy suburb from its inner-city neighbors. Shaker Heights mayor Wilson G. Stapleton, who also happened to be the Dean of the Cleveland-Marshall College of Law, stated, “As mayor of this community … I certainly am not going to go out and promote integration in the face of many of our citizens who would not favor it…” Stapleton’s comments highlight the fear many suburbanites had toward city folk--particularly African Americans--for they thought the newcomers' presence would lower property values and jeopardize the safety of their neighborhoods. This fear is what led Shaker to attempt to block off streets in 1959, although the barricades were not approved by city council.

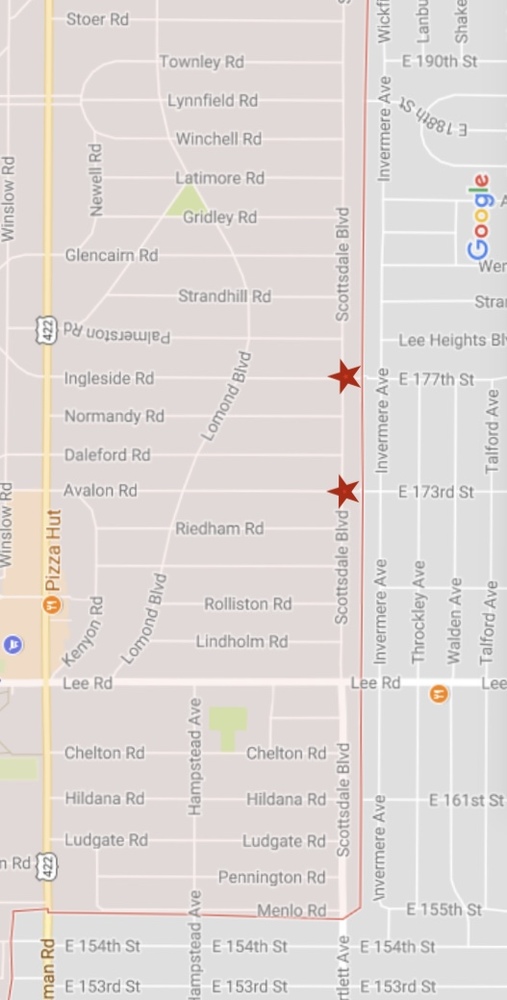

By 1976, the barricade debacle was in full swing and six streets had been blocked off as part of a 180-day trial. In 1979, two of the six original barriers became permanent, at Avalon and Ingleside Roads in the block between Scottsdale Boulevard in Shaker and Invermere Avenue in Lee-Harvard. With many residents upset about their permanent installation, the decades that followed saw an ebb and flow between local disputes and court battles. A Common Pleas Court hearing in 1985 resulted in an order to take down the barriers immediately at the suburb’s expense. The ruling was soon met by a 60-day reprieve ordered for Shaker Heights until the barricade dispute was officially settled. By 1987, after an 11-year conflict, the Ohio Supreme Court overturned the prior court rulings and stated that the suburb had constitutional rights when it first installed the traffic diverters. Shaker was now legally able to keep the barricades on the streets where they were permanent.

Shaker Heights was cheerful after the Supreme Court ruling, but with its excitement came discontent in Cleveland. Many residents worried about the relations worsening between the two cities. Frustrated with the pending debate, residents and community members of the Lee-Harvard neighborhood took matters into their own hands, planning protests and boycotts of Shaker businesses. One man, Everett Gregory of Invermere, along with fifty other demonstrators, held a protest at the Shaker Rapid one morning in October 1987. Gregory, 76 years old at the time, laid on the railroad tracks at 7:30 a.m., stopping five trains packed with more than 100 commuters. Although there were no injuries or arrests, Shaker Heights was upset and the mayor called his behavior undesirable and “uncivilized.”

Today, more than forty years later, two of the original barricades remain on Avalon and Ingleside Roads at Scottsdale Boulevard. Although they may be unusual locally, traffic diverters like these are also found elsewhere in the nation. In the late 1960s, an almost identical barrier was installed on Van Horne Avenue on the border of El Sereno and South Pasadena, California. Similarly, multiple roadblocks were installed in Detroit, Michigan, along Alter Road, a street that runs north and south along the border of Detroit and its wealthiest suburb, Grosse Pointe Park. In both of these cases, the barriers were ostensibly installed to prevent speeding motorists and to foster neighborhood safety. After comparing the barricades in El Sereno, Detroit, and Shaker Heights, it is crucial to note a common element. All of the barriers only have traffic signs facing the non-white neighborhoods reading, “Not a Through Street” or “No Outlet,” whereas the signs facing the predominately white suburbs are left blank and in the case of Shaker Heights, nonexistent. Placement of signposts suggests that barriers were intended only for one community and in all three of these examples that community happens to be of a lower-income minority.

Defenders of the barricades have always denied racist motives and mention that Shaker Heights is one of the most racially diverse suburbs in the United States. Other people question how race could be a factor when the Lomond neighborhood of Shaker Heights, which lies immediately to the north of the barricades, had a substantial black population when the barriers were erected. Approaching this question requires grappling with the messy intersection of class and race. In other words, we must consider the possibility that when middle-class blacks obtained homes in Shaker, perhaps they bought into an exclusive, if not exclusionary mindset. Shaker’s concerns on traffic and neighborhood safety are plausible and legitimate, but they are not necessarily independent from attitudes of class and race.

Whether the reasoning behind the barriers was racism or not, they remain an example of the trials cities face in the wake of suburban migration during the twentieth century. The political issues that were created by the Shaker barricades are a result of the dual political cultures in the two cities. Localism and the often conflicting ideologies of the two communities were at the core of the debates in the years that followed the installation of the barricades. More importantly, the legacy of the barricades left a stamp on the community. The changing demographics in Cleveland, without doubt, created racial tension between the city and its suburban neighbors. After exploring the Shaker barricades, one thing is for certain: Local community politics play the most important role in shaping racial tensions on the suburban fringe.

Images