The Desegregation of Cleveland Public Schools

A 40-Year Struggle for Public School Equity

A 1976 landmark federal court ruling challenged Cleveland to take long-overdue action to desegregate its public school system. Although slowed by litigation and disputes, the school district implemented crosstown busing to try to offset longstanding residential segregation patterns rooted in discriminatory real estate and lending practices. Compared to some other cities such as Boston, Cleveland's busing program was relatively peaceful, but it nonetheless produced its share of anxiety and unrest. While most Clevelanders agreed that change was necessary, the reality of transporting students away from neighborhood schools to unknown ones across the city challenged students, parents, educators, and the greater community to weigh the costs and benefits of personal comfort and social justice.

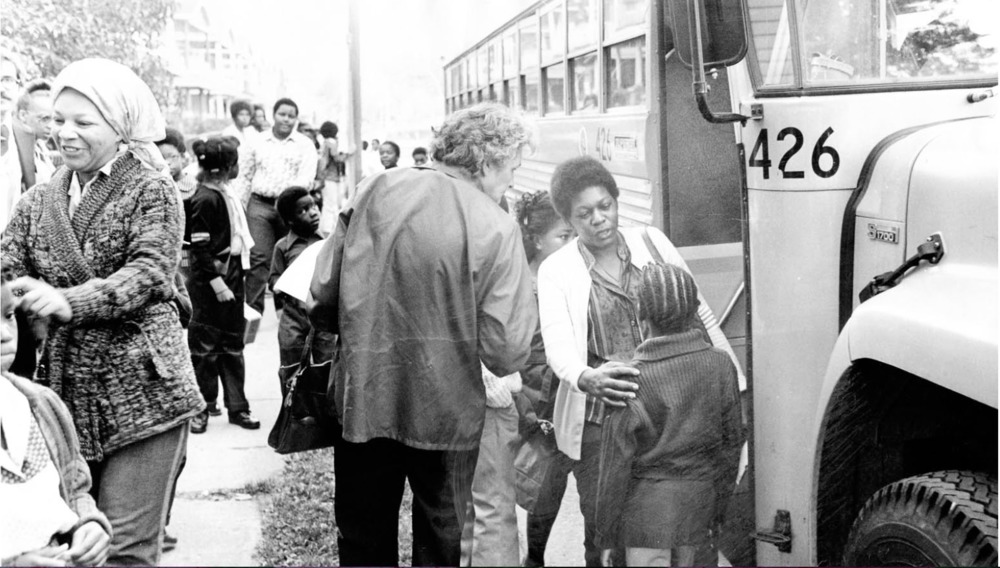

Gathering at the Lincoln Statue in front of the Board of Education building, members of WELCOME (West-East Siders Let’s Come Together) rallied to promote a safe and peaceful start of busing to achieve racial balance in the Cleveland Schools. The federal court order and plans were in place amid community unrest concerning the transporting of students to desegregate the schools beginning in the 1979-80 school year. However the reality of transporting students to achieve integrated schools throughout the city challenged students, parents, activists, and educators to meet on Cleveland’s major east-west bridge to mount an effort to insure student safety and keep the process peaceful. Members of CORK (Citizens Opposed to Rearranging Kids) also called for the uninterrupted and peaceful implementation of the initial phases of desegregation. These rallies marked the beginning of each of three phases of student transportation during the year. Despite their feelings, citizens of Cleveland wanted a peaceful school atmosphere.

The effort that began fifteen years earlier was inspired in part by activism in the South. Yearlong protests of discriminatory student assignment policies in the Cleveland Public Schools culminated with the tragic death of a protester at Stephen E. Howe Elementary School in 1964. School system scrutiny and debate continued over the ensuing decade and a lawsuit known as Reed v. Rhodes was filed with the Federal Court in Cleveland in 1973.

The litigation was long and complicated. Two years after the suit was filed on December 12, 1973, the late Judge Frank J. Battisti presided over a lengthy bench trial in 1975 and 1976. On August 31, 1976, Judge Battisti concluded that “the District and other Defendants, including the state board of education, had contributed, by both commission and omission, to an unconstitutional segregation of the Cleveland Public Schools.” The court permanently enjoined defendants “from discriminating on the basis of race in the operation of the public schools of the City of Cleveland, and from creating, promoting, or maintaining racial segregation in any school or other facility in the Cleveland Public Schools.” Both the state and local defendants were ordered to submit plans to desegregate the school district, which failed the court’s approval. A Special Master was appointed to develop a plan and later, on February 6, 1978, the court reaffirmed its earlier conclusion that the defendants were constitutionally liable for having maintained a de jure segregated public school system, and that these numerous constitutional violations demanded a system-wide remedy.

The court issued a remedial order directing Defendants to implement, beginning in September 1978, a “comprehensive, system-wide plan of actual desegregation which eliminates the systematic pattern of schools substantially disproportionate in their racial composition to the maximum extent feasible.” The broad remedial order required the defendants to desegregate administrative, supervisory and teaching personnel, to desegregate the schools, to develop creative educational curriculums, and to develop methods of monitoring compliance. The district court also ordered racial balance: “the racial composition of the student body of any school within the system shall not substantially deviate from the racial composition of the system as a whole.” Additional guarantees of student safety, counseling, extra curricular programs, transportation services were ordered among others.

Work then began to devise a method to remedy segregation in the Cleveland schools; plans were prepared to respond to all aspects of the court ruling. Also, the court re-appointed a Special Master, retained two experts on school desegregation, established the Office of School Monitoring and Community Relations (which it charged with rigorous monitoring of desegregation implementation), and ordered the appointment of an official Desegregation Administrator to be paid by the defendants.

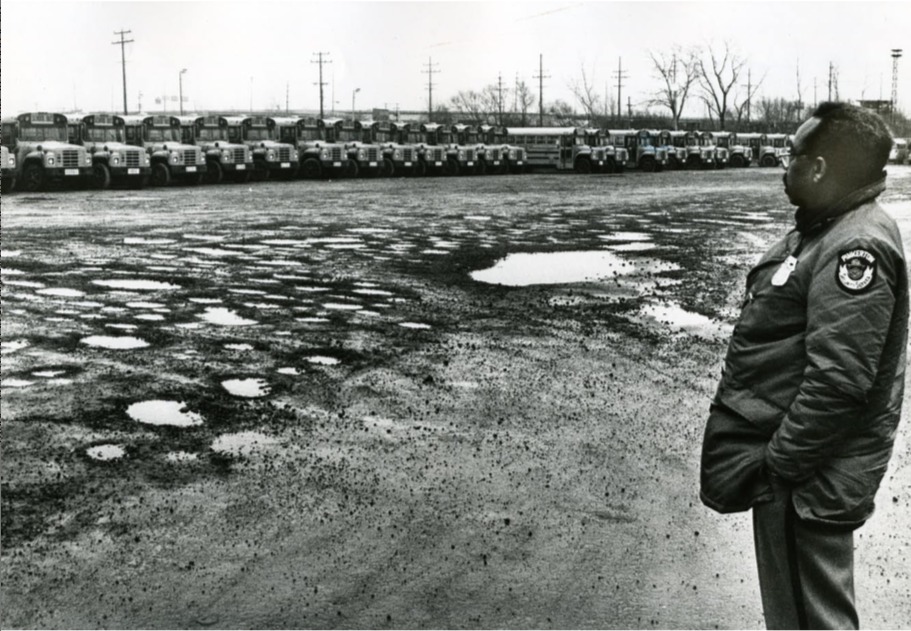

In order to comply with the plus/minus 15% racial benchmark, students were assigned and bused to schools across town to achieve the requisite racial balance in each individual school. When imbalances resurfaced, they were corrected by administrative orders and students were reassigned as needed. Following additional litigation and challenges in 1977, the court ordered implementation to begin. A limited number of junior high students were transported in 1978-79 school year followed by a three-phase system-wide implementation from September 1979 to September 1980.

Meanwhile, an unhappy community continued to protest the court approved remedies to be implemented. Pro and anti-busing advocates frequently picketed the school district headquarters, but the Court prevailed with its charge to proceed. Annually, throughout the 1980s, students were reassigned and bused to satisfy the court order. Bus rides for some students exceeded 80 minutes each way as east and west side students were assigned to cross-town destinations to balance the school populations. Despite the ongoing debate within the community, student transportation and assignments were never interrupted by civil disobedience. The intention to carry out court orders in a peaceful manner prevailed. In 1987, Judge Battisti authorized changes in pupil assignments without prior court approval if such changes were agreeable to the following three parties: the school district, the State Superintendent, and Plaintiffs' legal counsel. During the initial six years of full implementation, the district, the monitoring agency, and the court remained engaged in detailed review of the progress and the reorganization of district management.

In the 1980s, the city school system became predominantly nonwhite as a result of white flight out of the city and school boundaries. The Cleveland School District operated approximately 130 schools, 90% of which satisfied the 15% limitation every year. Dr. Gordon Foster, who had previously served as the plaintiffs' expert witness during the liability phase of this case, issued a report in 1988 that stated the district had ended any overt segregation or discrimination and was “the only majority black, large city system in the country which is totally desegregated.” In addition, as ordered, the Office of School Monitoring and Community Relations conducted a detailed assessment of the state of compliance with all outstanding remedial orders and concluded that the defendants had substantially complied with the 15% limitation and that any deviations could not be attributed to discriminatory student assignments. While a relatively small proportion of district schools each year had enrollments that exceed the maximum deviation, no evidence suggested that this was the result of discrimination on the basis of race in the assignment of students. The Monitoring Office's assessment recommended that the parties continue to work together to move the case forward.

In March 1992, the district court vacated over 500 orders upon joint motion of all the parties. However, there was a sense that the quality of public education had declined while the cost of operation had increased. The court thus urged the parties “not to hesitate to think about innovative programs and undertakings” that might ameliorate the situation in the school system. Judge Battisti further noted “the Court [had] not set out to run a busing company,” and directed the parties to address whether they believed “the interests of the students in Cleveland would be better served by an alternative student assignment plan,” and further suggested that parental and student choice become an important factor in student assignment within the Cleveland School District.

By 1998, U.S. District Chief Judge George W. White concluded that it was time to end the quarter-century court battle over integrating the 76,500-student district, saying "the purposes of this desegregation litigation have been fully achieved." In declaring the system "unitary," the judge found that the state and district had done all that could be expected to remedy the harm created by past segregation in the changing urban district. The persistent gap in student performance between black and white students, he found, "is the result of socioeconomic status and factors directly related to it, not race." In doing so, the judge also began the process to determine how much longer state education officials would keep day-to-day control of the district. He would hold hearings soon to consider lifting the 1995 order in the desegregation case that declared the district in crisis and stripped the elected school board of authority and arrange the control of the school district under the city’s mayor-appointed school board. Nonetheless the community, though grudgingly, had also cooperated during the twenty years to maintain a peaceful desegregation process in Cleveland.

Audio

Creator: Cleveland State University, Department of Education Date: April 12, 2017

Images