As the clock neared midnight on Halloween in 1897, a band of boys armed with hatchets and axes descended on the intersection of Scranton and Clark Avenue. In the spirit of the holiday, the weapon-toting youths began their vicious attack on the neighborhood's most peculiar structure--a 23 foot-high fence. The eyesore had been constructed three weeks prior as part of a dispute between neighbors D. Z. Herr and M. Moon. Following Moon's raising of a barn, Herr stacked boards to build the absurdly tall wall in an effort to block the view. Herr, convinced that his neighbor was attempting to strong-arm him into purchasing his property, refused to remove the barrier until the barn was removed. Moon declared that the fence did not bother him. As the vandals chopped away at the "spite fence," Herr emerged from his home and tried to intervene. Quickly restrained by the hoodlums, Herr watched as the structure was torn down and transported to a nearby vacant lot. The noise generated by the disturbance had attracted a crowd of hundreds from surrounding blocks, who idly looked on as the boards were doused with coal oil and set on fire. By the time the police arrived, the neighborhood had joined the boys in singing and dancing wildly around the flames. The police sat by and watched, but strangely were unable to identify any of the boys despite their best efforts. No arrests were made. When the fire finally died down, a sign was erected on the site: "Here lies the remains of the fence that Herr built."

At the turn of the 20th century, Halloween in Cleveland offered a night of excess and structured chaos for the city's children and young adults. Similar throughout the United States, this ancient holiday that symbolically transgressed the boundary between life and death provided communities a moment of release from social norms. Mischievous acts that would generally be deemed as impermissible by community standards were overlooked, and even encouraged. Adults openly reminisced on their past exploits, and children were expected to aid fairies, witches and imps in a night of delinquency. Reflective of the festivities that occurred at the intersection of Scranton and Clark avenues, a perceived shift in communal roles underpinned the holiday tradition. Most often, though, Halloween night offered an outlet of revenge and sense of retribution for the city's powerless youth. It would have been no surprise to any adult that had crossed local children to experience the wrath of vengeful spirits come Halloween night.

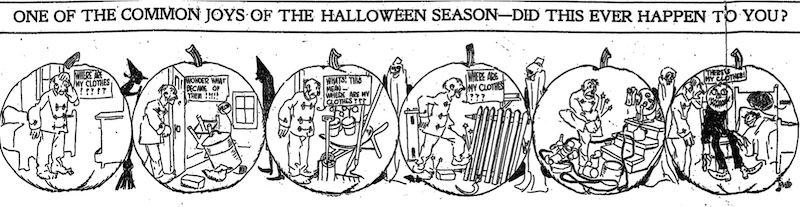

Every November 1st, Cleveland newspapers provided a familiar list of pranks and acts of vandalism that had occurred during the prior evening. A description of a "quiet" Halloween by the Cleveland Police in 1905 recounts what was fairly standard fare for the night of celebration. Iron and wood gates were torn from their hinges, doors were tied to verandah posts, windows in grocery stores were broken for some light looting, a wagon was rolled down an embankment and set ablaze, an occupied chicken coop was relocated to the roof of a home, a six-foot tall barricade was placed in a major intersection, bonfires were set in residential streets, and Wade Park pond became a receptacle for stolen items of all sorts. Other Halloween traditions included chalking doors, ringing house-bells, pelting homes and policemen with produce, leading livestock into church steeples, and throwing dummies in front of automobiles and streetcars. Arrests were uncommon, and generally reserved for the most disruptive offenders.

While hooliganism would remain a public expectation through the mid century, a tradition of "handouts" became commonplace in Cleveland by the late 1930s. Masked children began to show up on doorsteps, chiming "we want a handout." While this tradition of blackmail can be traced to Old-World roots of the holiday, it first found favor in some Cleveland neighborhoods at about the time of the first World War. The costumed beggars were treated with cookies, popcorn balls, candy, doughnuts and cider. This precursor to "trick-or-treat," however, was just one aspect of a much larger change in how the holiday was celebrated. Largely due to the effects of Halloween's commercialization following the turn of the century, the holiday was gradually co-opted by adults; the popularity of costume parties and festive public events grew, and traditional festivities were increasingly sanitized. By the end of the 1950s, Halloween had ceased to be a night for hell-raising throughout the city. The holiday tradition of flipping social roles did not completely disappear, however, as the pranks and vandalism of yesteryear provided credence to the empty threats of masked marauders extorting payment from their community.

Images