Cleveland's Zoo Goes on Safari

The Transition Away from Collection and Colonialism

Over ninety percent of all animals currently displayed in American zoos were born in captivity. Highly regulated breeding and exchange programs, however, replaced a much different method of acquiring zoo animals beginning in the 1960s.

A walk through the Cleveland Metroparks Zoo offers visitors a glimpse into a carefully curated society of animals from around the world. While the vast array of species provides a representation of life on different continents, it's highly unlikely that an inhabitant of the zoo has ever been outside of the United States. Over ninety percent of all animals displayed in zoos were born in captivity. Of course, this has not always been the case. Highly regulated breeding and exchange programs between zoos accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums supplanted the practice of removing animals from their native environment.

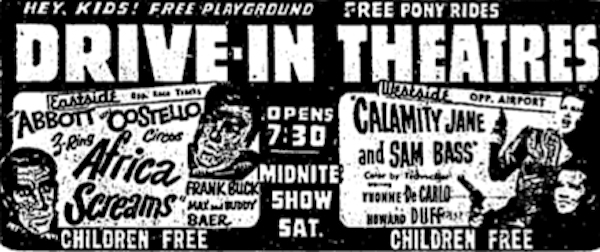

The development of American zoos up until the 1960s hinged on an animal trade often steeped in colonialism, exploitation and a euro-centric worldview. It was an era characterized by famous animal traders and highly publicized trapping expeditions in distant lands. These excursions generated public interest and promoted a vision of zoos as educational institutions. Both the diversity of species provided by traders and a focus on big game animals helped draw in a curious public, and shaped what was expected of city zoos. In Cleveland, this period of institutionalization was pushed forward under the direction of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History and Zoo Director Fletcher Reynolds. In an effort to create a world-class zoo, expeditions were planned to Eastern Africa for the collection of animals in 1950, 1955, 1959 and 1960. The safaris aided in both the expansion of the zoo and its rebranding as an educational civic organization.

For the first half of the 20th century, the zoo primarily housed and exhibited domestic animals for the viewing pleasure of spectators strolling through park grounds. These animals were not only more affordable, but did not require specialized care. Dating back to the zoo's formative years, with Jepthia Wade's deeding of a deer herd to the city along with his land, the primary means of growing the native collection was through gifts. While animals were also purchased with park funds, these acquisitions were meant to enhance or replenish existing collections of domestic species.

In 1931, approximately 300 of the zoo's 420 animals were domestic species. The small collection of exotic animals housed by the zoo, though, was the highlight of the park. Animals such as lions, elephants and alligators were showcased in the scattershot menagerie, and acted as a gauge for the zoo's status. Generally acquired with donated funds or as gifts from prominent citizens, these non-domestic species were readily available due to an established animal trade in Africa, Asia and South America. The supply lines were set up to meet the demand of pet stores, vaudeville, circuses and private collectors by the middle of the 19th century. This international animal trade provided a framework from which American zoos developed. Species made available for sale would subsequently be identified with American zoological gardens.

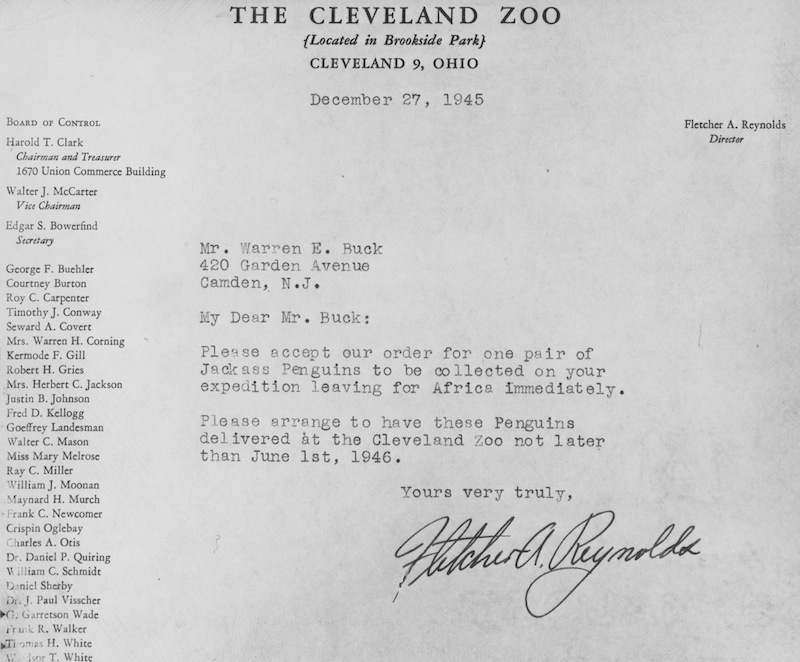

With the transfer of management of the Brookside Zoo to the Cleveland Museum of Natural History in 1940, the zoo slowly began to develop as a professional zoological garden. As part of this process, the new administration took an active approach to curating and expanding the collection. To emerge as a leading zoological garden required the acquisition of a diverse array of non-domestic species. The board replaced over 100 animals during its first year, and, soon after, discontinued the practice of indiscriminately accepting donations. Drawing upon the experience of prestigious zoological societies throughout the United States, an expedition was planned with the goal of both attracting public attention and bringing in new animals.

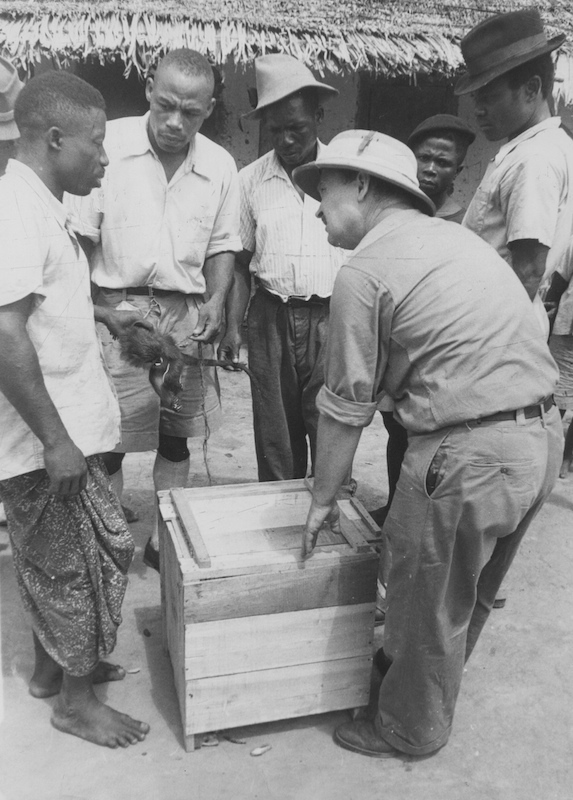

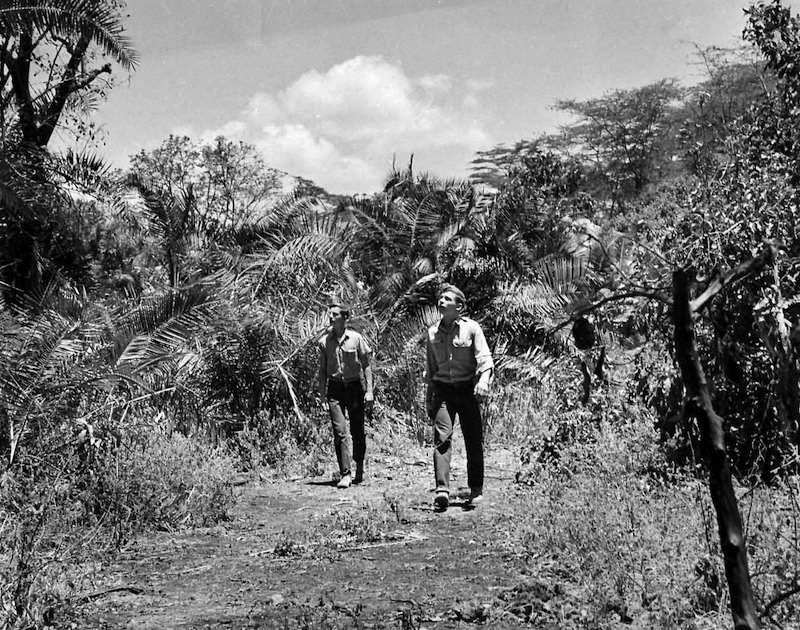

Fletcher Reynolds undertook Cleveland Zoological Park's first African expedition in 1950. During a three-month trip to the Cameroons in West Africa, Reynolds collected over 150 species of animals. While a safari conjures images of Reynolds chasing down game in the wilderness, the Zoo Director's main purpose was to examine and purchase animals from dealers. By personally heading the expedition, he set up supply lines that the Cleveland Zoological Park could use in the future. The zoo showcased its new inhabitants upon his return, which included baby gorillas, chimpanzees, venomous reptiles, birds, a cheetah and a leopard. In addition, Reynolds returned to Cleveland with photographs and film of the expedition. These were presented to a public fascinated with Africa. The animals and images brought back from the Cameroons were meant to be evidence of Cleveland Zoo's evolution into an educational resource for Natural History.

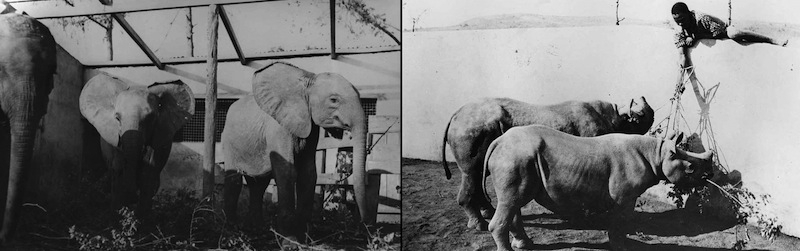

The next animal collecting expedition occurred in 1955. Plans to construct a state-of-the-art $600,000 Pachyderm Building were made with the passage of a bond issue in 1952. The objective of the safari was to obtain elephants, hippopotamuses, rhinoceroses and giraffes from East Africa to inhabit and promote interest in the new exhibit. The trip proved successful; with $65,000 slated for the purchase of animals from dealers, the zoo also acquired tortoises, birds, baboons, monkeys, a cheetah and a wildebeest. The massive freight was transported by ship from East Africa to New York.

Later expeditions sponsored by the Zoo were of a much smaller scale, but were meant to meet the same ends as the previous safaris. A 1959 expedition to Africa acquired over a hundred birds and what would become one of the zoo's most iconic inhabitants - Karen the Bongo. At the time, Karen was the only bongo in captivity; both her capture and the expedition were a symbol of the zoo's rising prestige and status as a valuable civic asset. The final zoo-sanctioned safari occurred in 1960. Working with the Board of Education, a ten-week animal identification competition was held by the Cleveland Zoo that culminated in the naming of two students to accompany an expedition to East Africa. Despite the trip being cut short due to political and social unrest in the African nations, the zoo acquired 18 birds, two chimpanzees, and three monkeys.

That same year, seventeen African countries declared independence. With the dismantling of colonial influence in Africa, the age of collecting expeditions for the Cleveland Zoo came to an end. While the established animal trade would remain a means for purchasing new animals, the conservation movement of the 1960s would help bring into question both the ethics and environmental impact of removing animals from their native habitat. The focus of the Cleveland Zoological Park was redirected towards internal development, rather than the accumulation of animal species.

Images