Euclid Beach Park Riot

Violence and the Color Line at Cleveland's Leading Amusement Park

On August 4, 1946, almost one year after the dropping of atomic bombs on Japan and the end of World War ll, a picket line appeared in front of Cleveland's Euclid Beach amusement park for the first time in its history. Protesting the park's long-standing policy of excluding African Americans from using the park's roller rink, swimming facilities, and dance hall, an interracial crowd of over 100 picketers, including many uniformed World War ll veterans, held signs reading, "We Went to Normandy Beach Together — Why Not Euclid Beach?" Others compared the park's owner with the recently defeated leader of Nazi Germany: "Hitler and Humphrey believe in super race."

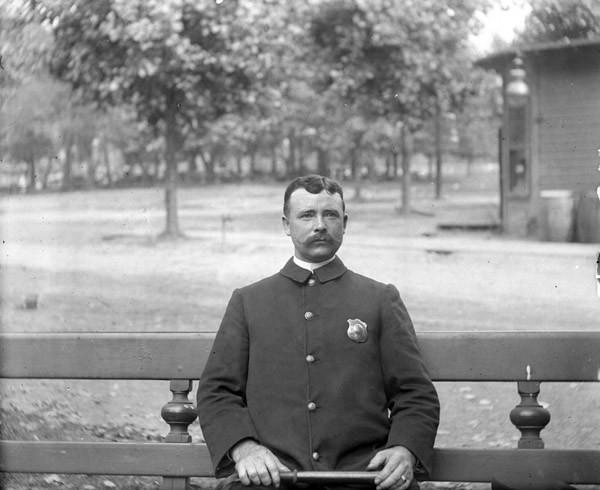

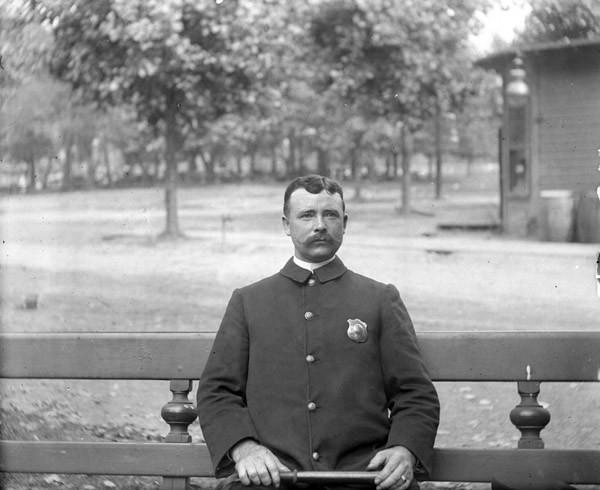

In the weeks that followed, protests continued and violence broke out. On August 23, Albert Luster, a member of the interracial civil rights group the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), was severely beaten by Euclid Beach Park policemen. Luster had planned to join an interracial group of ten or so CORE members who, like other groups that summer, sought to test the park's policies by attempting to enter the dance hall together. But he had arrived late to the park; the group had already been roughly ejected from the park by the time he showed up. Park policeman Julius Vago found Luster sitting by himself on a park bench and set upon him with his nightstick in an apparently unprovoked attack.

Then, on September 21, two black Cleveland police officers scuffled with members of the Euclid Beach Park Police, and Patrolman Lynn Coleman ended up with a bullet in his leg. Coleman and Henry Mackey, off duty at the time, observed an interracial group of CORE members being treated roughly by park policemen as they tried to enter the dance floor. When the two Cleveland Police officers attempted to intervene, a fight ensued and Coleman's gun went off, hitting him in the leg. Other Cleveland Police officers detailed to the park soon intervened. Coleman was taken to the hospital, while the Euclid Beach Police officers involved in the fight, after undergoing questioning at Central Police Station, were released, the Cleveland Police Department opting not to pursue charges against them. The events that night came to be known as the Euclid Beach Park Riot.

Discussions soon began in Cleveland City Council that would result in the passage, the following February, of an ordinance that explicitly outlawed discrimination at Cleveland's amusement parks. Racial segregation at Euclid Beach seemed to be coming to an end. However, before the start of the 1947 season Euclid Beach leased its roller rink and dance hall to private clubs not bound by the amusement park ordinance. The bathing facilities in the park closed for good in 1951 after only a few summers of interracial swimming.

It is no coincidence that the 45-year policy of segregation at Euclid Beach met its most serious challenge in 1946, a year after the end of World War ll. The war heightened the likelihood of racial confrontations as black and white Clevelanders attempted to define what it would mean for race relations in the city. After the war ended, many white Clevelanders looked nostalgically to the years before the Great Depression and the war, and hoped to return to what they considered to be normalcy and stability after so many years of disorder. For many white Clevelanders, that meant returning to a racially divided community. Black Clevelanders, on the other hand, had been emboldened by their participation in the war effort — both at home and abroad — and anti-Nazi rhetoric seemed to discredit racist ideologies at home. They sought to solidify gains made during the war and stake a claim to full racial equality in the postwar city. These differing visions of postwar Cleveland collided at Euclid Beach in 1946.

Audio

Images