Rusin Cultural Garden

The plot of land that makes up the Rusin Cultural Garden is located along East Boulevard. It was dedicated in June, 1939.

Most Rusyns (also commonly spelled Rusins) immigrated to Cleveland in the period from 1880 to World War I. The Rusyns are an Eastern Slavic ethnic group who speak a dialect known as Rusyn or Lemko. Rusyns descend from Ruthenians but, unlike some of the groups related to them, did not adopt the term Ukrainian in the early twentieth century to describe their ethnicity. Cleveland's Rusyns trace their heritage to the Carpathian Mountains, which is the second longest (932 mi) mountain range in Europe. This chain of mountains stretches in an arc from the Czech Republic (3%) in the northwest across Slovakia (17%), through Hungary (4%) and Poland (10%) to the Ukraine (11%). It then runs south to Romania (53%) before arcing back east to the Iron Gates (gorge) on the Danube River between Romania and Serbia (2%).

One of the earliest (1890) Rusyn settlements in Cleveland was located within a Hungarian community along Orange and Woodland Avenues. As these groups grew they both moved eastward along the Union and Buckeye Avenues. A second Rusyn settlement also developed in Tremont and by 1906 Rusyns were settling as far west as Lakewood. By the 1930s, more than 30,000 Rusyns lived in the city. After World War II, however, Rusyns, like many others, moved to the suburbs in large numbers. In 1983, approximately 25,000 Rusyns still lived in the Greater Cleveland area, but most of the original Rusyn neighborhoods had long been abandoned. In 2009, the Carpatho-Rusyn Heritage Museum opened at the St. John the Baptist Cathedral in Parma to educate the public about the history and culture of Rusyns.

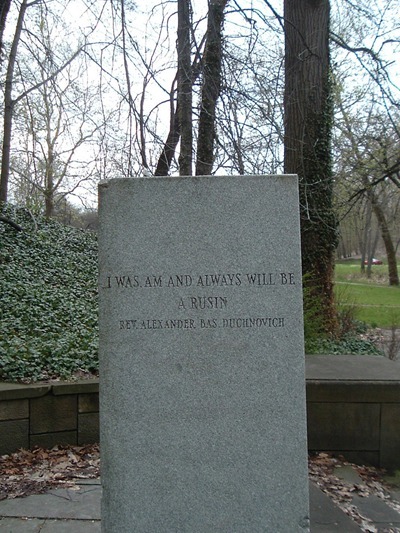

Pastor of Holy Ghost Greek Catholic Church, Reverent Jseph Hanulya, was also the head of the Rusin Cultural Garden Association. In May, 1952, Hanulya unveiled a bust of Alexander Duchnovich. A Greek Catholic priest, Alexander Duchnovich (1803-1865) wrote prose and poetry in the Rusyn language, and also wrote the Rusyn National Anthem. The bust has since been stolen and no longer stands in the garden.

The Cultural Gardens have often incorporated symbolism or design elements that subverted the message of unity and reflected ethnic tensions in Europe and Cleveland. Clever choices of sculptures and honorees by ethnic communities also brought the conflicts so evident in Europe and its history to the chain of gardens. An example of this sort of conflict can be found in the Rusin Garden's choice to honor Alexander Duchnovich; a champion of Rusyn language and identity who defended the Rusyn language from Hungarian rule in the nineteenth century. Both the Slovak and Czech gardens celebrated similar themes. It was no mistake that the Czech, Slovak, and Rusin gardens arrayed themselves across a boundary street from the contiguous German and Hungarian gardens. Location can sometimes suggest just how powerfully old cultural conflicts were felt.

Images