Passersby often turn their heads as they pass the Vitrolite, a historic building located at 2915 Detroit Avenue. The striking 18,000-square-foot building stretches a full city block southward to Church Street. But rather than its exterior, the building's interior explains its name. A step inside the original showroom, currently occupied by Patron Saint Cafe, reveals a wall of Vitrolite glass tiles manufactured by the company through much of the twentieth century.

The Vitrolite was originally constructed in 1926 as a showroom and service space for the Vitrolite Company, which serviced the region with a revolutionary structural glass product that shaped architectural and interior design trends nationally and internationally for nearly four decades.

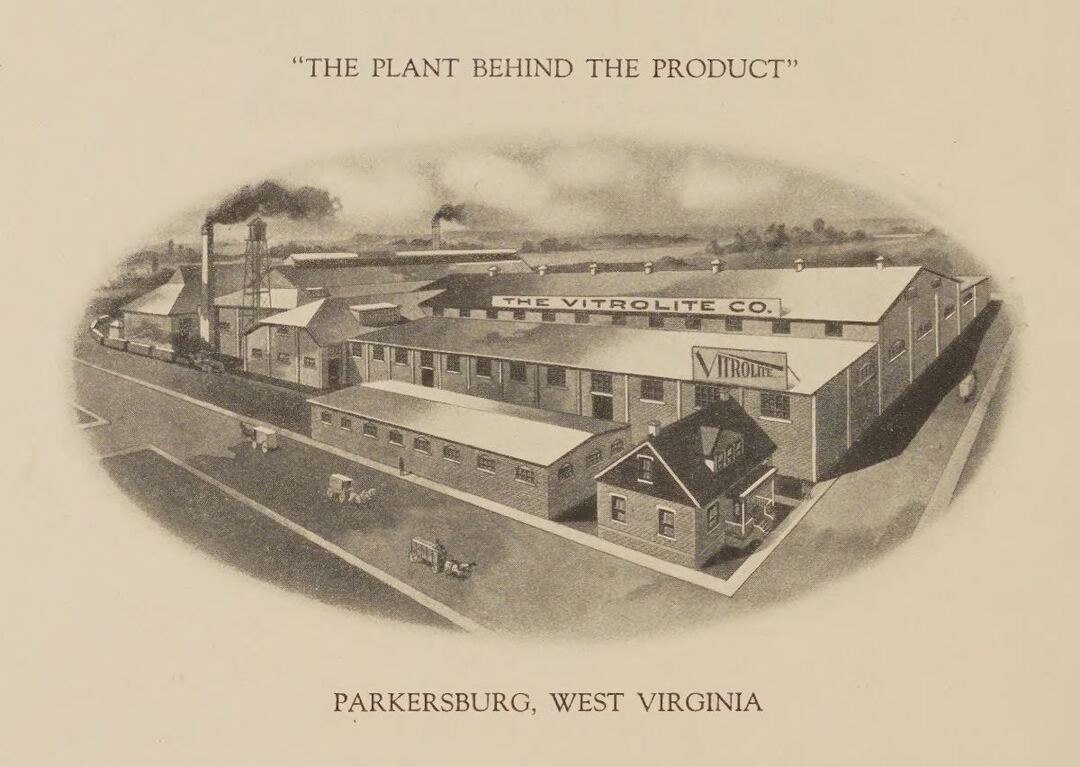

Vitrolite was a brand of pigmented structural glass in the form of tiles and sheets known for a clean, shiny, colorful appearance. It was originally produced in 1908 in Parkersburg, West Virginia, by the Meyercord-Carter Company, whose founder George Meyercord of Chicago was anxious to expand his advertising sign business. Meyercord gathered investors and experienced glass manufacturers to guide the production of ‘milk’ glass. Parkersburg was in the middle of the ‘glass belt’ spanning northeastern West Virginia, southern Ohio, and western Pennsylvania. Several glass manufacturers in this area relied on the abundant energy provided by coal and natural gas in West Virginia and the ease of transport afforded by the Ohio River. Meanwhile, technological advances in the early twentieth century transformed the glass industry from a labor-intensive, manual process to machine-driven mass production. Instant business success prompted Meyercord to change the company’s name in 1910 to the Vitrolite Company with a second factory in nearby Vienna, West Virginia.

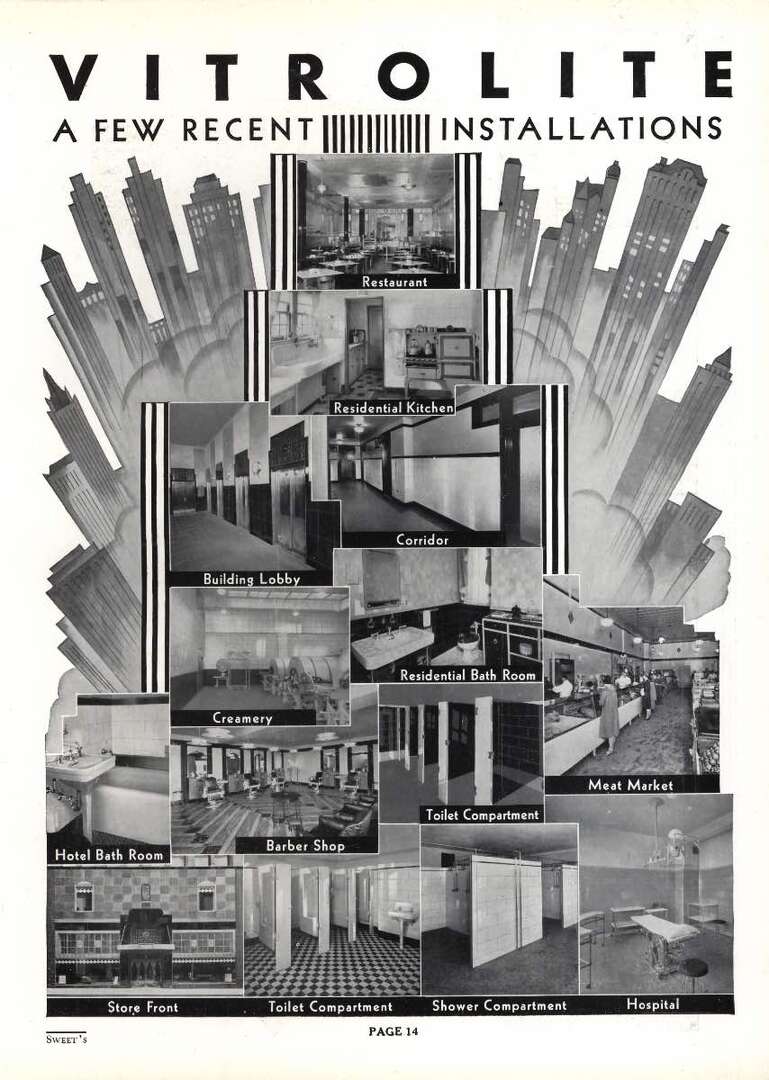

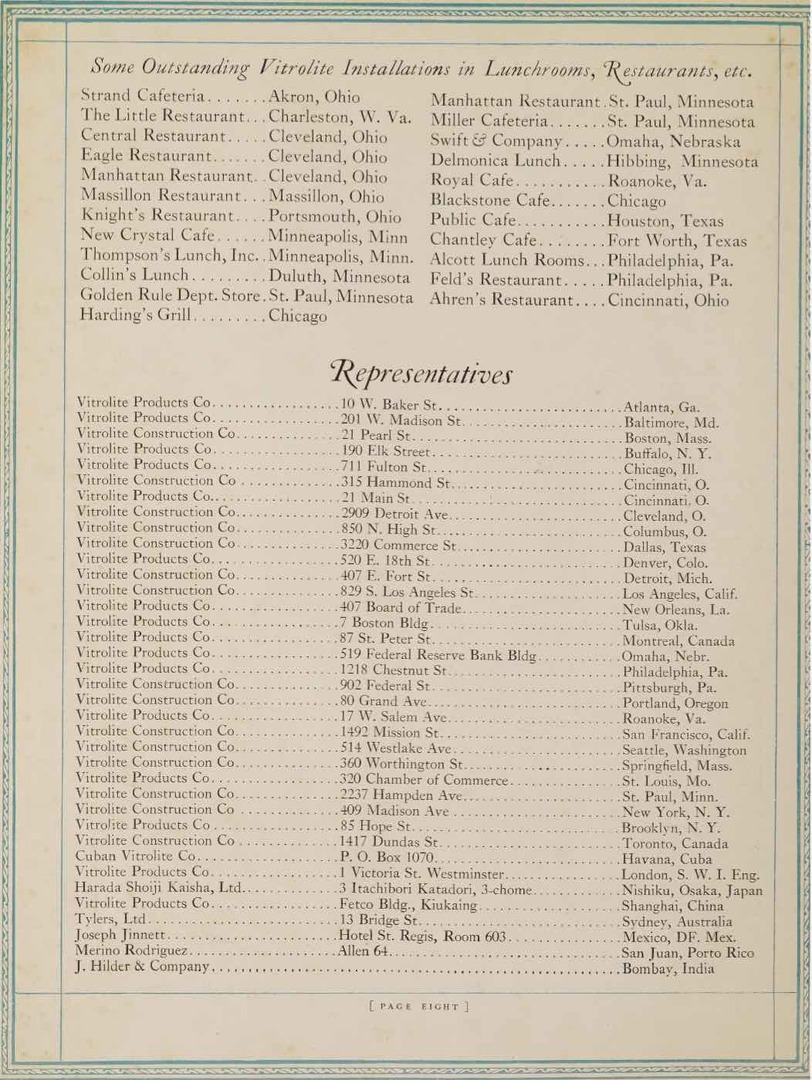

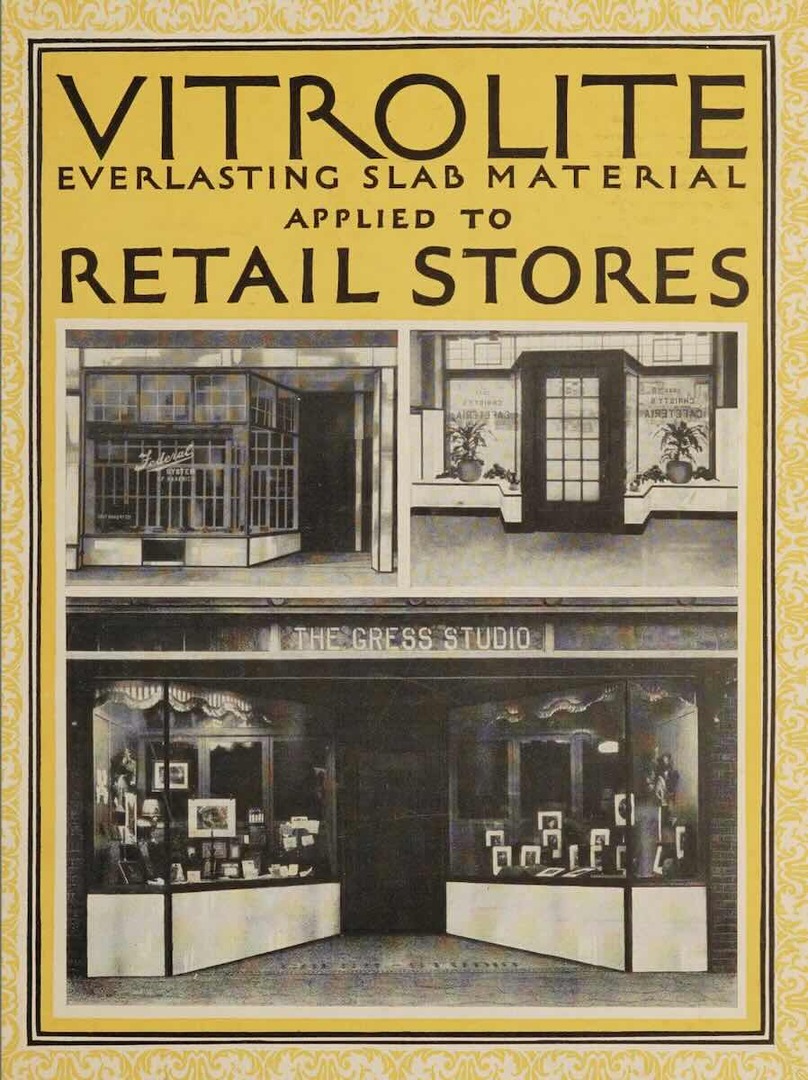

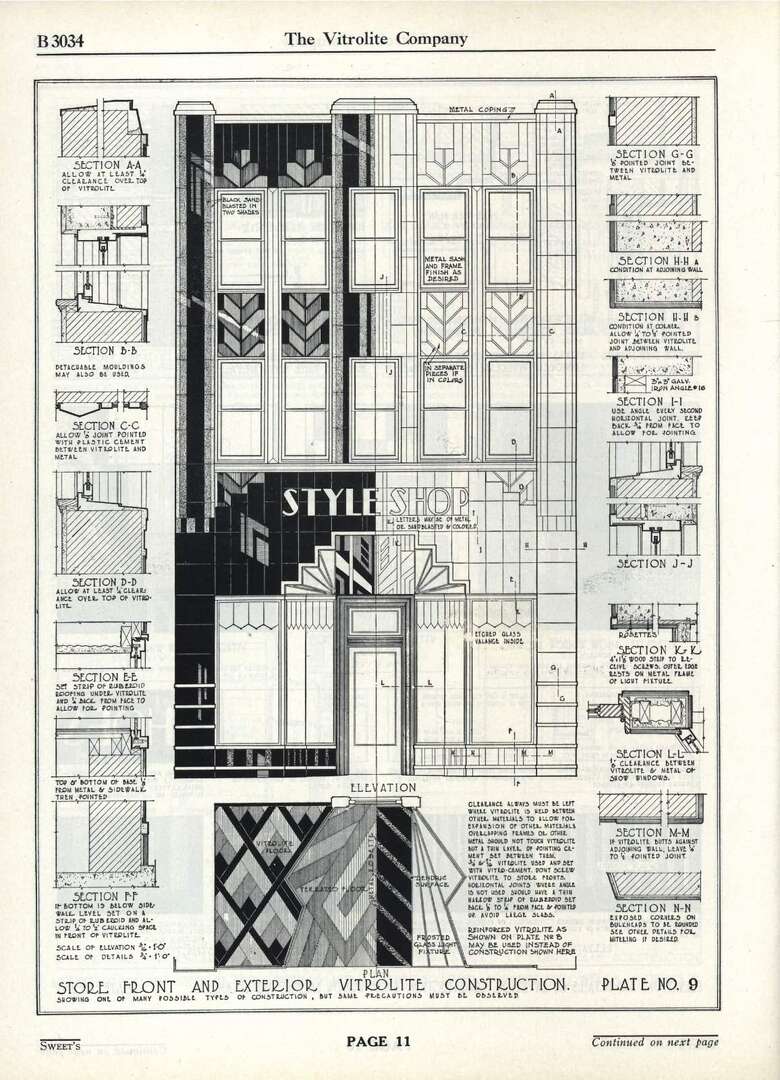

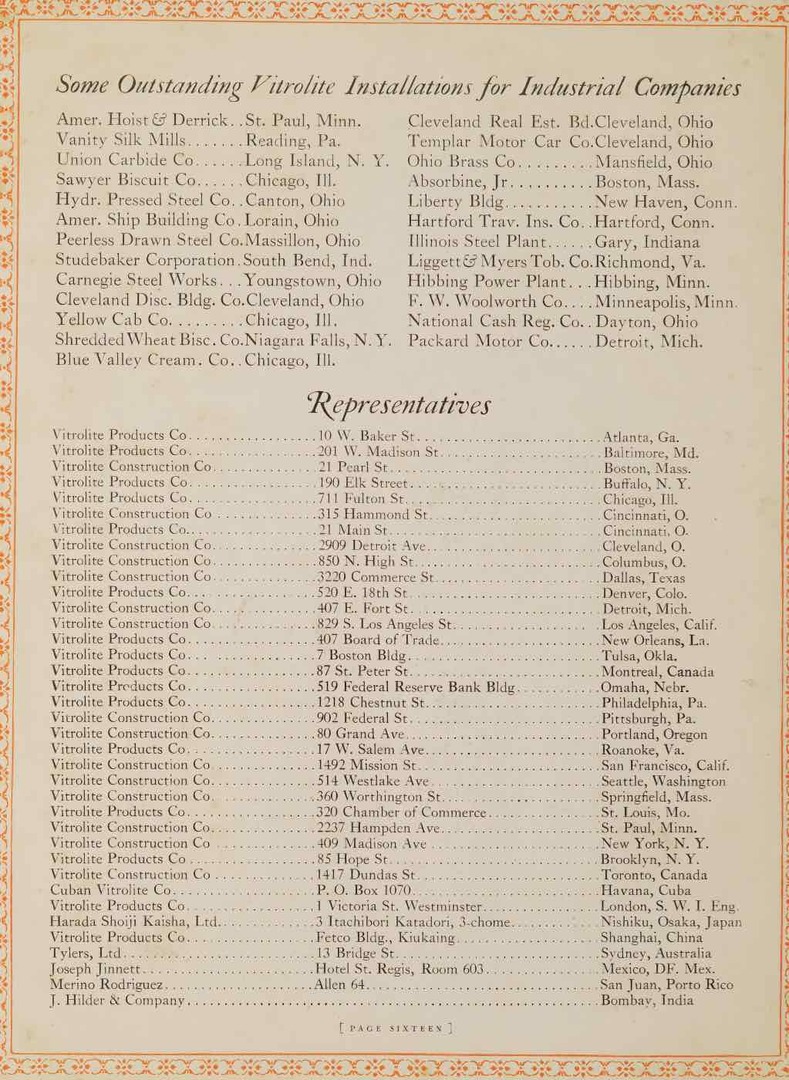

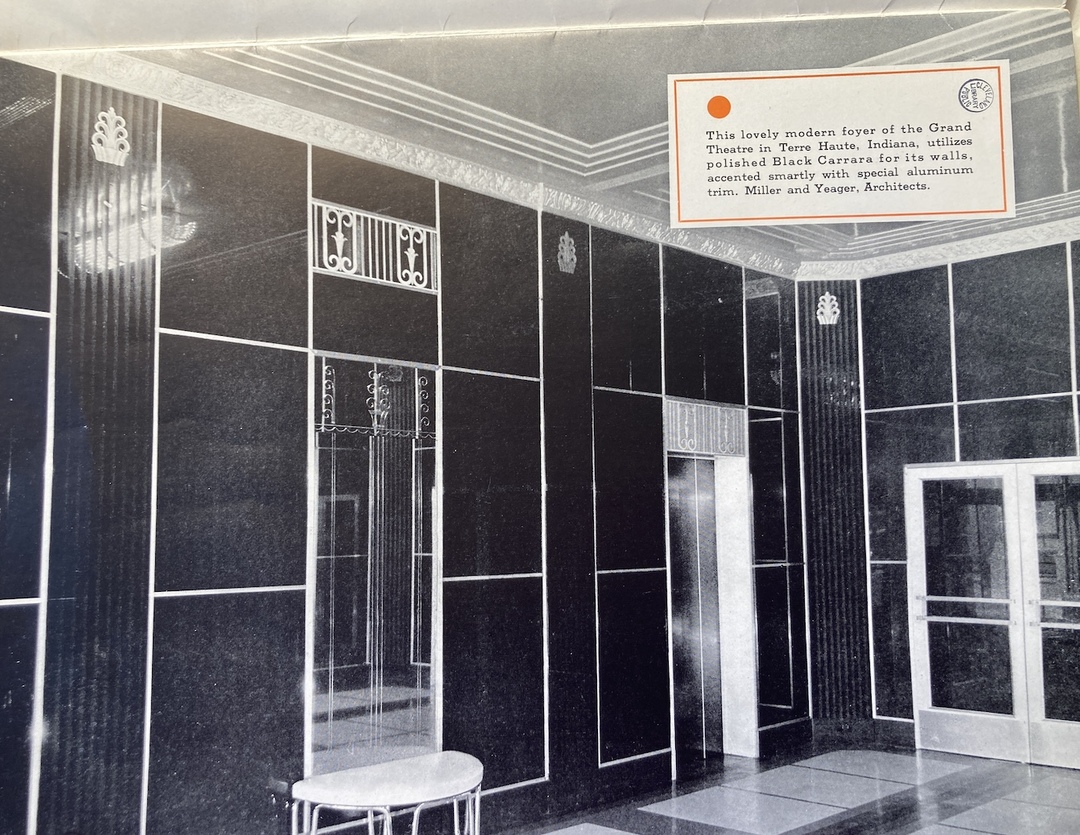

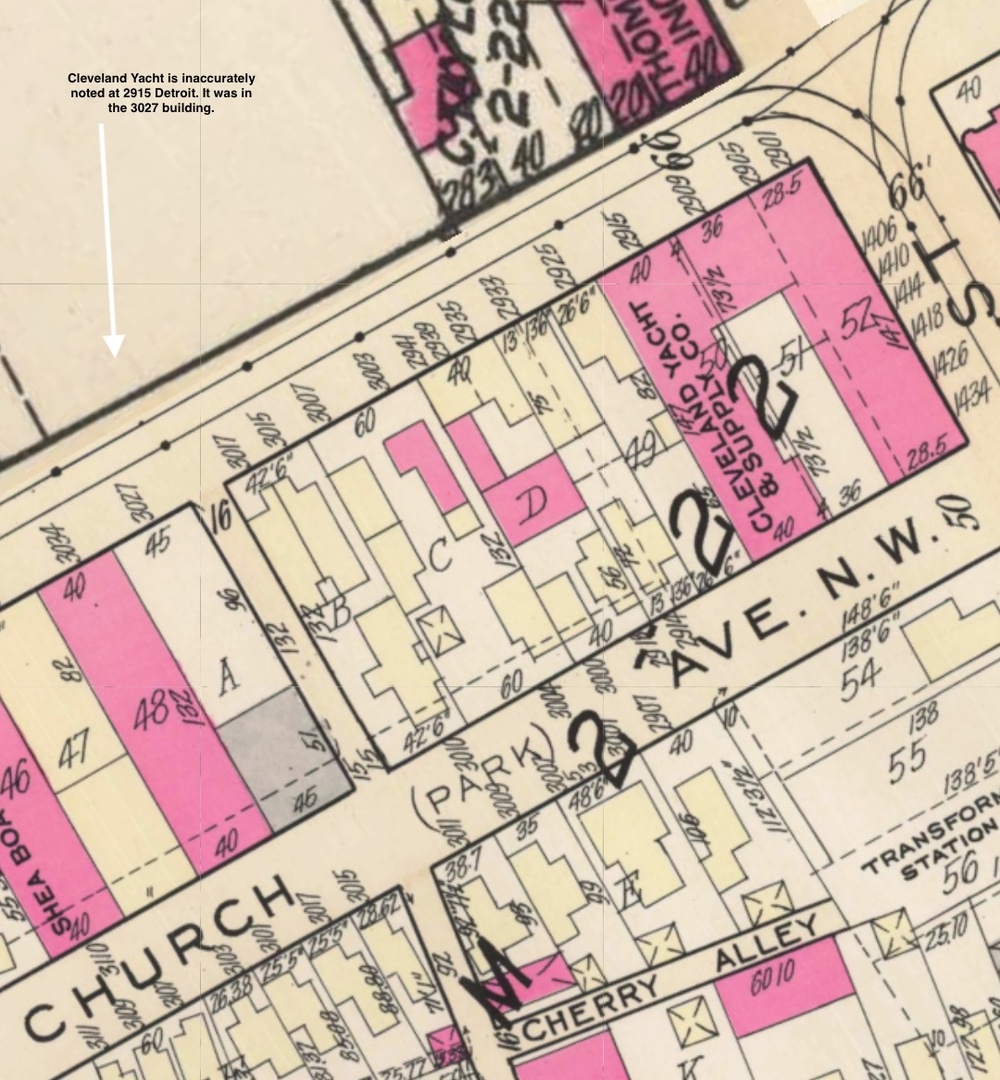

Thanks to its affordability and versatility, Vitrolite rapidly became popular throughout the U.S. and even abroad, and by 1923 it boasted representatives in 32 North American cities plus London, Sydney, Osaka, Shanghai, and Bombay. The company had established a Cleveland presence by 1912, when it operated out of 650 Woodland Avenue, but by 1921, the company had moved to 2909 Detroit, the building immediately east of where it established its new showroom in 1926. The product found many applications that fit the popular Art Deco, Streamline, and Moderne architectural styles of the 1920s through the 1950s. It typically served as a marble substitute for building design and applications. While it originated in oil-whie (milk glass), Vitrolite ranged in color from black, beige, and ivory to greens, blues, jade, and gray. One very popular application, storefront remodeling, was seen most everywhere in the country and involved the application of Vitrolite panels directly over masonry walls to ‘glamorize’ the presentation of window goods via clean, shiny, marble-like surroundings. Interior applications featured colorful etched and engraved Vitrolite glass-paneled lobbies and elevators in many American downtown buildings.

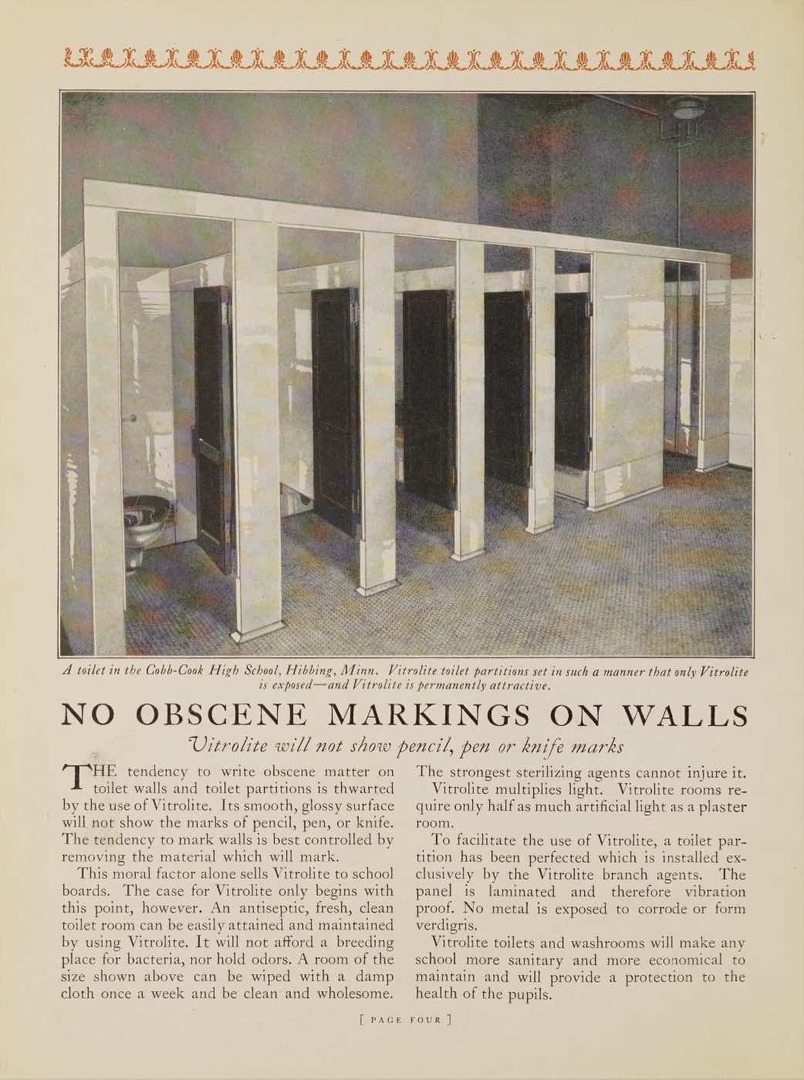

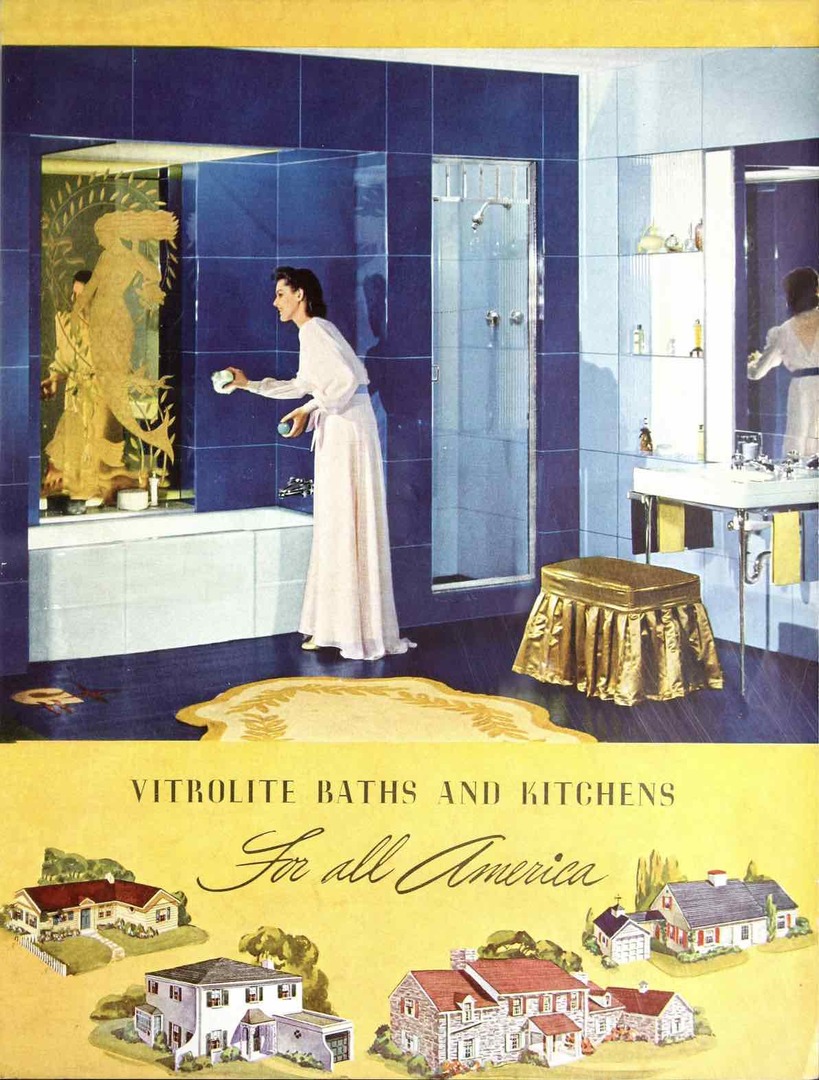

In addition to wall veneers, the glass was utilized in decorated lobbies, restroom partitions, and tabletops and countertops in restaurants, including in downtown Cleveland's Hippodrome Cafeteria and Mills Cafeteria. Hospitals, barber shops, and beauty parlors also found Vitrolite panels and fixtures conducive to cleanliness and ease of maintenance. By the 1920s, the product was so common in the kitchens and bathrooms of residential homes that its name was lowercased as “vitrolite.” Ultimately, artistic applications of Vitrolite emerged, including sculpted and etched paperweights, ash trays, glass figurines, and knick-knacks.

Vitrolite’s popularity convinced other manufacturers to make other brands of structural glass. These included Marietta Manufacturing in Marietta, Ohio, which produced the Sani-Onyx and Sanirox brands, and Pittsburgh Plate Glass, makers of the Carrera brand. And Vitrolite itself caught the eye of another Ohio manufacturer. In 1935, Libbey-Owens-Ford (LOF), of Toledo, (“Glass City”) Ohio bought Vitrolite. However, World War II marked the beginning of the end of Art Deco design and with it the reduced popularity of the structural glass applications. Though LOF continued production of Vitrolite into the 1950s, the firm became better known as a leading producer of sheet and automotive glass. In contrast, Pittsburgh Plate Glass, headquartered in Pittsburgh and now known as PPG Industries, remains in the structural glass industry.

Although Vitrolite has not been publically displayed inside Cleveland’s Vitrolite building for several decades, the building’s distinctive Vitrolite-clad interior showroom has remained. The building was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2004, and from 2003 to 2022 it was home to the Intermuseum Conservation Association (ICA–Art Conservation), one of the world’s leading art conservation laboratories. The current owners and tenants acquired the property in 2022 to renovate the space. Architect Jonathon Kurtz designed a facade for the Church Street building entrance to mimic the historic design of the Detroit side with the endorsement of Cleveland’s Landmark Commission. Today the Vitrolite building houses the Harness Collective, a mixed-use building with a cycle spinning studio, cafe, yoga studio, children’s play area, and collaborative space for start-ups.

Images