Thomasville Quail Plantations

The Hanna and Wade Winter Retreats in South Georgia's Red Hills Region

The names Hanna and Wade are immediately familiar to most longtime Clevelanders. These families amassed fortunes in industries such as iron, oil, coal, steel, tobacco, shipping, telegraphs, railroads, and finance at a time when Cleveland was on the rise, and they poured tremendous sums of philanthropic money into education, healthcare, and the arts. Their names appear throughout the city—Hanna Building, Hanna Theatre, Hanna House at University Hospitals, Wade Park, Wade Oval, Wade Lagoon, Wade Chapel—and one will find their names among the prominent funds that support the collections of the Cleveland Museum of Art. However, fewer Clevelanders may know that the Hanna and Wade legacies are just as visible in the Red Hills region of southwestern Georgia near the Florida border.

Starting in the 1890s, wealthy Clevelanders were among the northern elites who transitioned from staying at the fashionable winter resort hotels of Thomasville, Georgia, to owning former cotton plantations, transforming them into private retreats and quail hunting grounds. One of the earliest Cleveland investors in the Red Hills was Howard Melville Hanna, born in New Lisbon, Ohio, in 1840. After moving to Cleveland in 1852 and serving in the U.S. Navy during the Civil War, Hanna invested in an oil refinery that he sold to his friend John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company of Ohio, as well as in iron and steel, tobacco, and shipping. He also worked closely with his older brother Marcus Alonzo Hanna in the M. A. Hanna Company.

In 1896, while his brother Mark was actively managing William McKinley’s presidential bid, “Mel” Hanna bought not one but two large former cotton plantations in the pine-studded Red Hills southwest of Thomasville. At the time, Thomasville remained a popular wintertime destination for wealthy northerners, even as new railroads built by Henry Flagler and Henry’s Plant opened newer resorts deep into Florida. While Florida’s coastal resorts would eventually eclipse Thomasville’s popularity, the Red Hills continued its appeal as a hunting paradise with hundreds of thousands of acres of woodlands known for abundant bobwhite quail, wild turkeys, doves, and ducks.

Hanna’s first purchase was a plantation previously owned by his nephew, Charles Merrill Chapin, who had bought it in 1891. (Chapin’s mother Salome Marie Hanna Chapin was Mel Hanna’s younger sister.) The estate, which had originally belonged to Paul Coalson, included an antebellum house that probably dated to the 1830s. Upon acquiring the property, Hanna renamed it Melrose Plantation. A few months later, he bought the adjacent Pebble Hill Plantation, whose main house—built in 1850 by some of the thirty-seven people enslaved by planter William Henry Mitchell—had been unoccupied for 15 years.

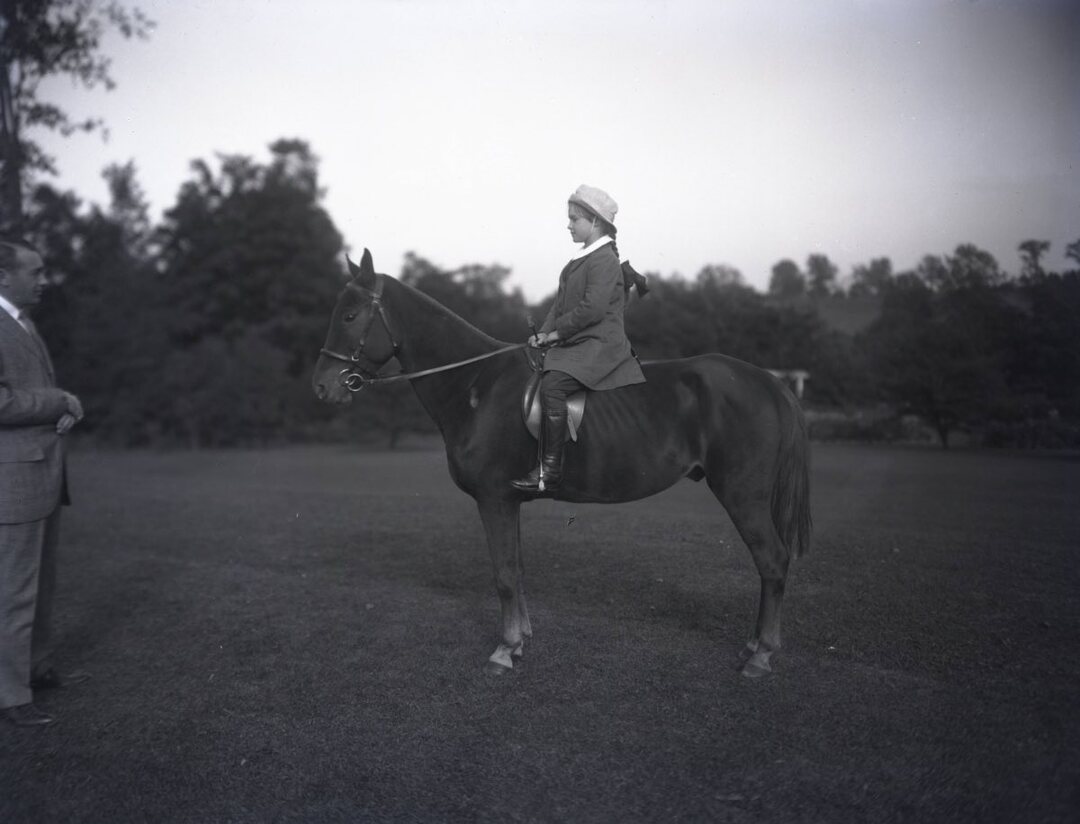

Mel and his wife Kate spent their winters at Melrose, joined by their children Kate Benedict, Howard Melville Jr., and Mary Gertrude. In 1905, Hanna expanded the main house, and after his death in 1921, his son hired the renowned Cleveland architectural firm Walker and Weeks, to design Georgian Revival–style cottages, barns, and outbuildings. Among these was a private theater, Showboat, which hosted the first private screening of Gone with the Wind in 1939. After Hanna Jr.’s death in 1945, his daughters, Fanny (Mrs. Julian Castle Bolton) and Kate (Mrs. Warren Bicknell Jr., named for her aunt) shared the estate. Eventually, in 1952, they divided Melrose, creating a separate estate for Kate and Warren Bicknell called Sinkola Plantation.

Meanwhile, in 1901, Mel Hanna deeded Pebble Hill to his daughter, Kate Benedict Hanna Ireland, for the symbolic sum of one dollar. She lived there with her husband, Robert Livingston Ireland (also of Cleveland), and later with her second husband Perry W. Harvey. The Harveys expanded Pebble Hill from 3,000 to 10,000 acres. In 1934, two years after her husband died, Kate Harvey’s antebellum main house burned down, leaving only the loggia standing. She then commissioned Cleveland architect Abram Garfield (son of U.S. President James A. Garfield) to build a new fireproof 28-room mansion combining Federal and Greek Revival styles. Kate Harvey lived just four months after its completion. Pebble Hill then passed to Her daughter, Elizabeth “Pansy” Ireland Poe, inherited the estate and lived there for four decades. In 1950, she established the Pebble Hill Foundation, ensuring preservation of the estate as a historic house museum, which opened to the public in 1983.

In 1905, Hanna purchased a third Thomasville estate, Winnstead Plantation, which he gifted to his daughter Mary Gertrude and her husband, Coburn Haskell. Haskell, a former employee of the M. A. Hanna Company, had left to pursue the manufacture of his 1899 patented invention of the modern golf ball. After his death in 1922, Mary Gertrude remained at Winnstead until her passing in 1945, after which the family sold the property.

The Hanna legacy in Thomasville extended well beyond these estates. Kate Benedict Hanna Ireland’s son, Robert Livingston Ireland Jr., co-owned Foshalee and Ring Oak plantations with Cleveland businessman David S. Ingalls. When Mel Hanna’s grandson Howard Melville Hanna III died in 1936, his widow Pamela remarried Cleveland lawyer and M. A. Hanna president George M. Humphrey. Humphrey built a mansion at Milestone Plantation, which became an occasional retreat for President Dwight D. Eisenhower during Humphrey’s tenure as Secretary of the Treasury. By the middle of the twentieth century, other Hanna descendants owned additional quail plantations around Thomasville.

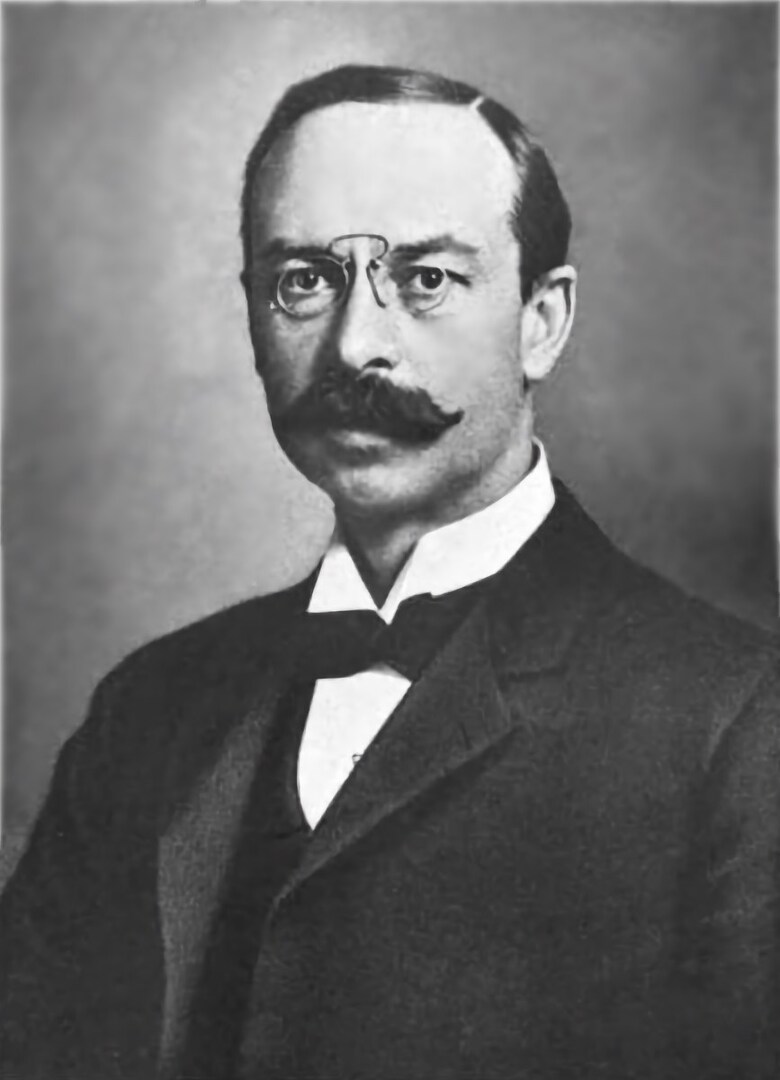

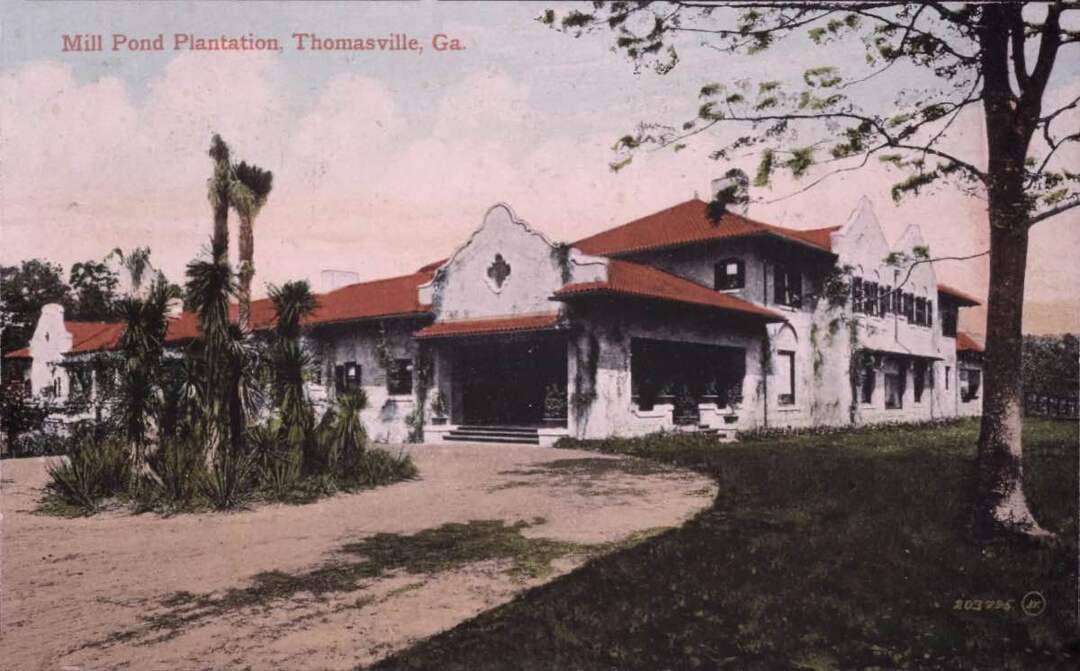

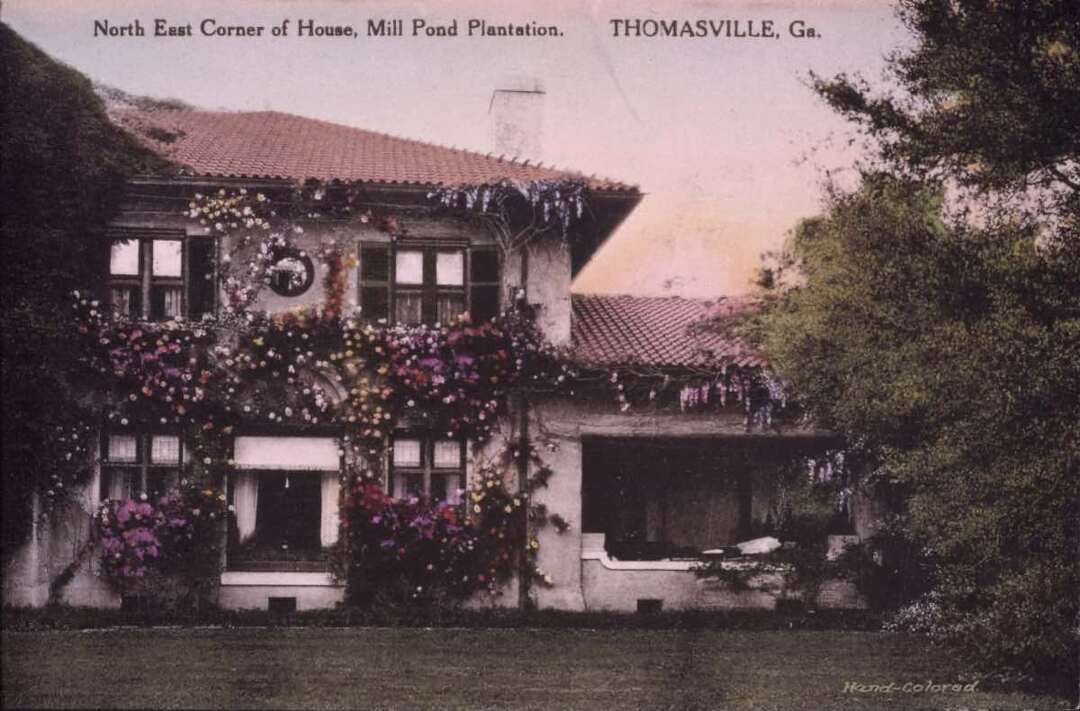

Yet the Hannas were not the only Clevelanders who wintered in and bought land in Thomasville. Another was Jeptha Homer Wade II, grandson of Western Union Telegraph founder Jeptha Homer Wade and an early benefactor of the Cleveland Museum of Art. In 1903, Wade began assembling parcels for his own winter retreat south of Thomasville, eventually controlling over 10,000 acres. In 1905, he commissioned Cleveland architects Hubbell and Benes, the same firm that had designed Cleveland’s Wade Memorial Chapel, to design Millpond—a Spanish Revival mansion that featured a glass atrium flanked by a loggia. For Millpond’s gardens, Wade retained Frederick Law Olmsted’s apprentice Warren H. Manning, who also designed the grounds at the Vanderbilts’ Biltmore House in North Carolina, the Seiberlings’ Stan Hywet Hall in Akron, the Mathers’ Gwinn in Bratenahl, and Wade's Valley Ridge Farm in Hunting Valley.

Wade and his wife Ellen wintered at Millpond until her death in 1917 and his nine years later after which Millpond was placed in a trust for their children, Jeptha Homer Wade Jr., George Garretson Wade, and Helen W. Wade (Mrs. Edward B. Greene). Helen inherited her brothers’ interests, and when she passed away in 1958, her daughter Helen Wade Garretson Perry owned Millpond for nearly forty more years. Thereafter, the home continued to be owned by descendants of Wade.

The Hannas and Wades, like other Cleveland industrialists and their counterparts in other northern cities, took former cotton plantations once worked by enslaved or sharecropping Black workers and reimagined them as winter retreats, albeit still depending on Black labor. They retained the term “Plantation” in their names but repurposed the land for hunting quail. Ironically, it was the longstanding practice of burning fields and forests before each next cotton-planting cycle that had created a setting conducive to quail plantations. In their desire to maintain this quality, winter residents came to embrace conservation practices such as those advanced by forester and ornithologist Herbert Stoddard, who penned an influential book on quail conservation in 1931.

Though they learned to embrace forest conservation and wildlife management, quail plantation owners could not overcome wider environmental changes after World War II, including habitat loss amid conversion of farms to exotic grasses or short-rotation pine plantations, pesticide use, and suburban sprawl. By the end of the century, the quail “harvest” plummeted by more than 75 percent. Today, family-owned quail plantations like Wade’s Millpond and conservation organizations are working to restore quail populations. Meanwhile, historic sites such as Hanna’s Pebble Hill and South Eden (formerly Melrose and Sinkola) offer visitors a glimpse of the leisured lifestyles that Cleveland-based manufacturing wealth permitted in Thomasville.

Images