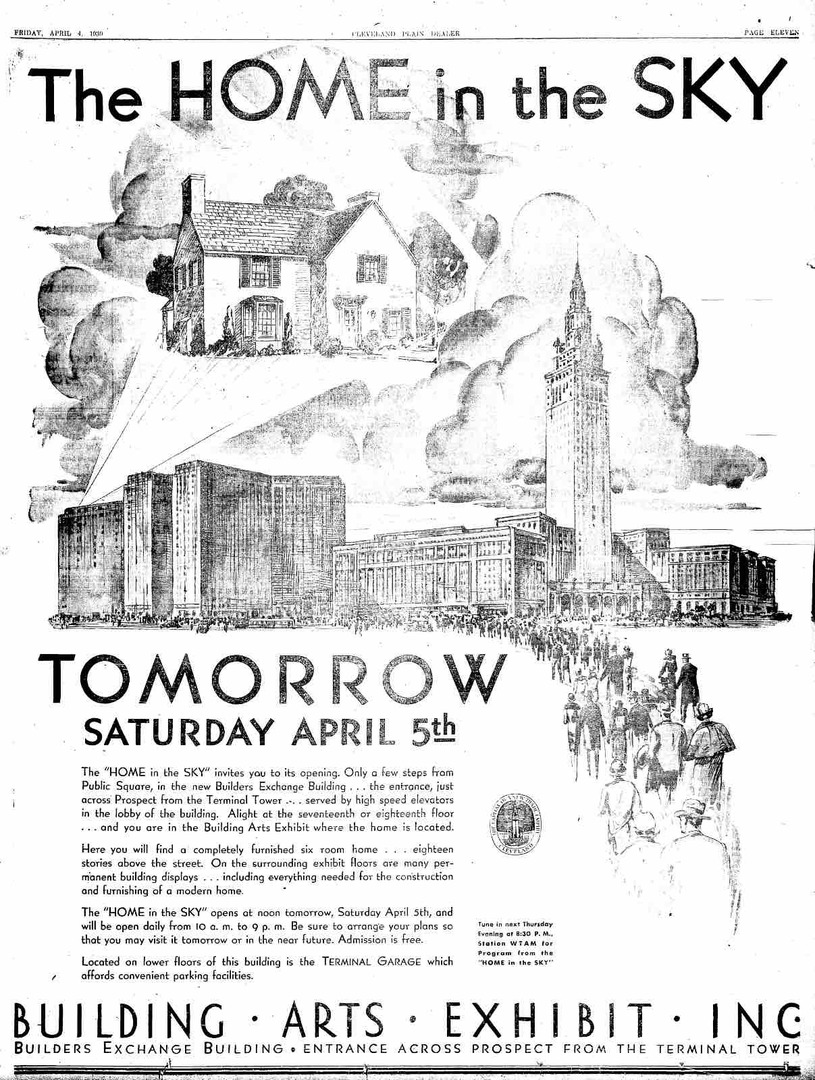

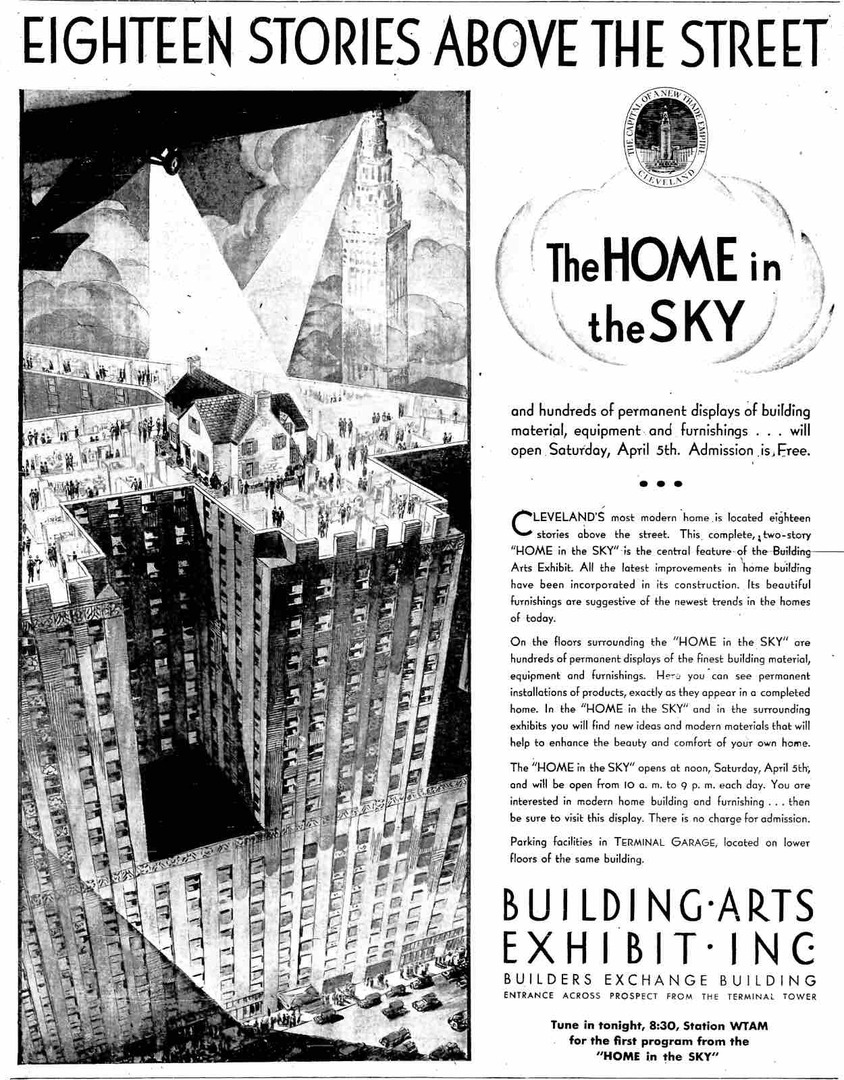

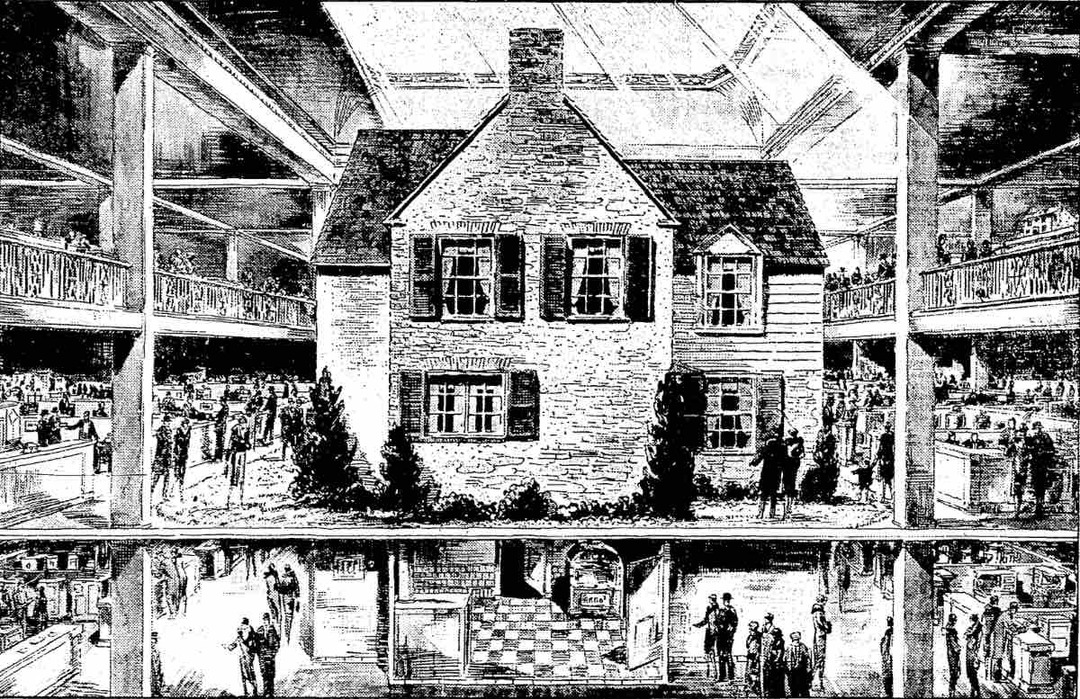

On the evening of Friday, April 4, 1930, members of the Builders Exchange (a nonprofit building trades association) dined with their families in the Guildhall, a restaurant on the tenth floor of the association’s headquarters building in the Terminal Group. After dinner, they rode elevators up to the Exchange’s brand-new indoor model home exhibit, known as the Home in the Sky. Governor Myers Y. Cooper delivered a dedication speech broadcast from Mount Gilead, Ohio, and pressed a radio-control button to remotely illuminate the home. The next day, airplanes circled the skyscraper and dropped “festoons of roses.” Then Mayor John D. Marshall and his wife turned the key to officially open the house to the public. Speaking amid a worsening Great Depression that threatened the construction industry, Marshall predicted reassuringly, “Here home ownership will be fostered.” By the close of the opening weekend, an estimated 10,000 people had viewed downtown's novel new attraction.

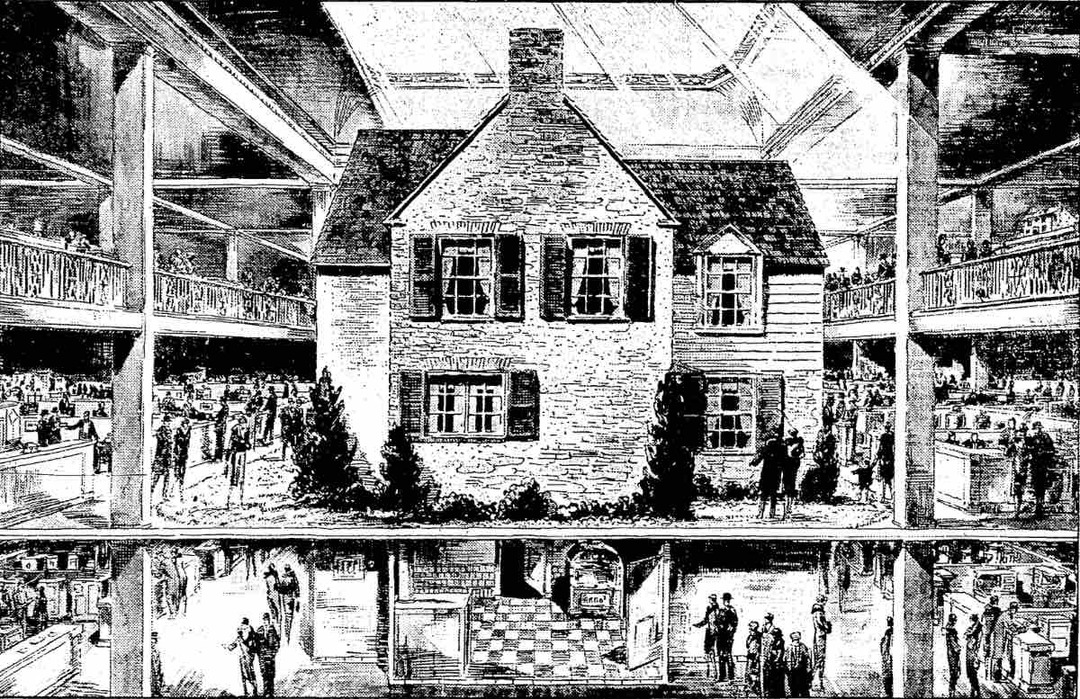

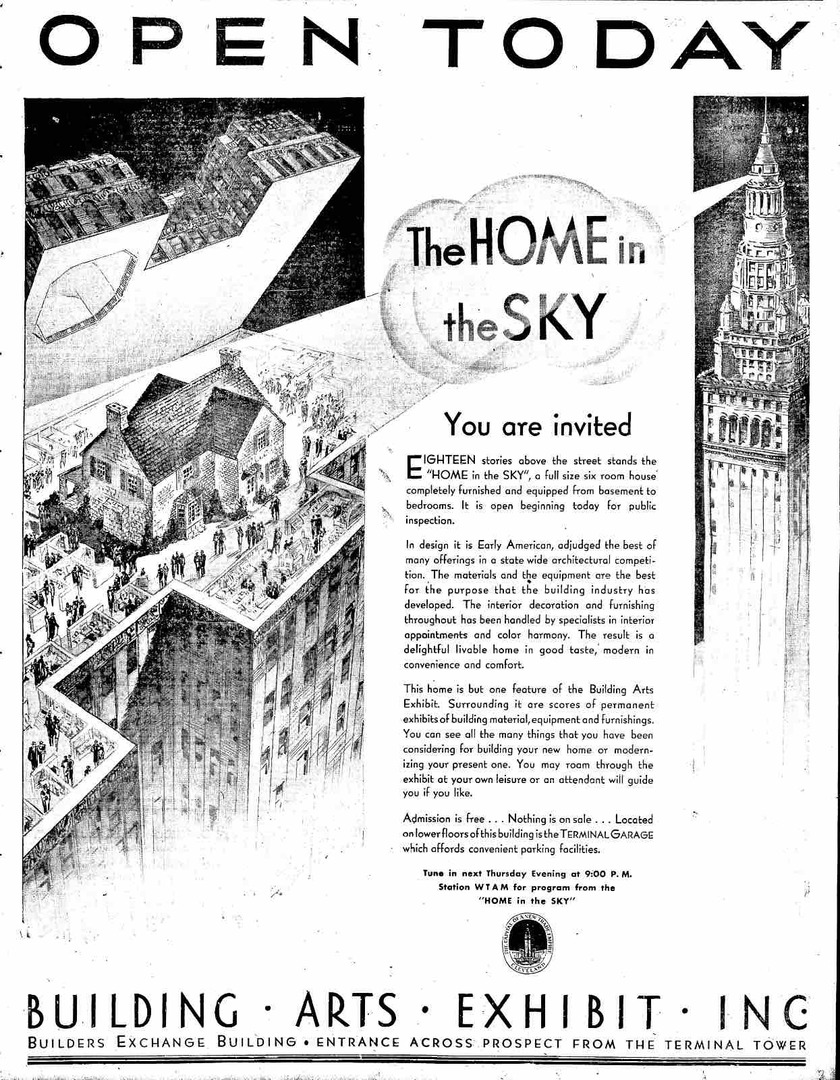

The Home in the Sky was a 39 x 31 foot, two-story, six-room, Colonial-style house erected by Building Arts Exhibit Inc. in a 51-foot-tall open court on the 17th and 18th floors of the Builders Exchange Building. A gallery on the 18th floor enabled close inspection of the house's second story and roof. The house showcased the latest building materials, home decoration and furnishings, all surrounded by a landscaped lawn and additional "Building Arts" displays. The Home in the Sky emerged from plans by the Builders Exchange in the late 1920s. In cooperation with the American Institute of Architects Cleveland Chapter and the Better Homes Association, it held a statewide contest in 1929 to design the house. Fred J. Abendroth of Dunn & Copper Architects in Cleveland won first prize, beating about 2,500 other contestants. The house’s conservative design mirrored that of the nearby Terminal Tower, which mimicked 20- to 30-year-old skyscrapers in New York and Chicago rather than embracing the modernism of Art Deco.

The house's conservative architecture was perhaps best evoked in the Cleveland Builders Supply Company’s explanation of the use of “Cleveland Rustic” face brick for much of the exterior: “Vision, with closed eyes, a home of brick nestled amongst groups of trees and masses of flowering shrubs; a home, not glaringly new in appearance, but reflecting the softened, weathered touch which is Nature’s gift alone; a home redolent with the atmosphere and age-old glamour which typifies the architecture of our forefathers. This pictures, briefly, the effects created by ‘Cleveland Rustics’ in ‘The Home in the Sky.’”

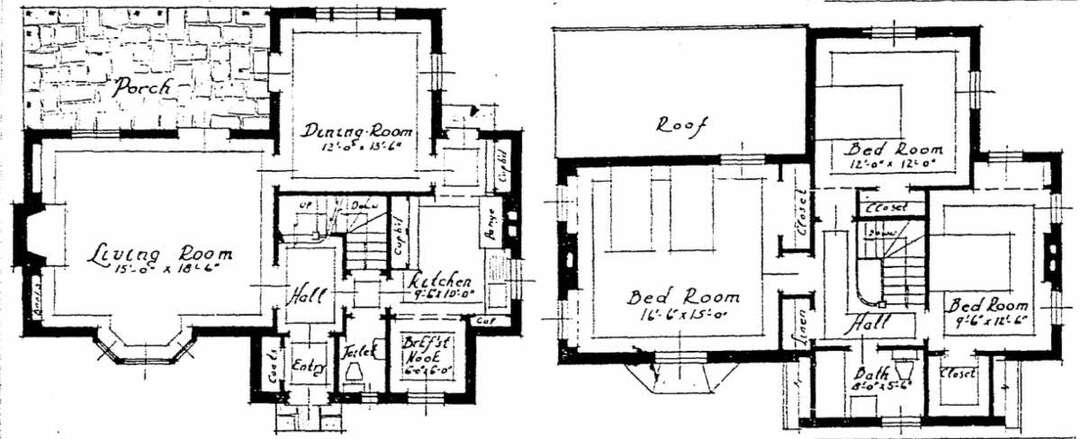

The May Company’s home decorating department furnished the Home in the Sky. The house’s first floor featured a vestibule with coat closet; a living room with a bay window, a fireplace, and wooden mantel flanked by bookcases with a door opening onto a garden porch; a dining room; a modern kitchen with the latest electric appliances and a breakfast nook. The second floor included a stair-hall, three bedrooms with closets (one of them a nursery), and a green and mauve bathroom. In the basement was a pine-paneled recreation room with a fireplace, bright-red leather lounge chairs, and laundry with “electrical labor-saving devices designed to lighten the work on the modern home-maker.”

Visitors were free to roam the house on their own or to take a guided tour led by Florence LaGanke, who also served as the exhibit’s director of women’s activities. They could not only see a range of materials and furnishings in what the Plain Dealer called "a doll's house for grown-ups" but also obtain expert advice on construction, furnishings, home management, and even landscaping and gardening techniques. WTAM also broadcast a regular biweekly program from the exhibit to explore such topics. Clubs were also welcome to reserve space for their meetings.

In its first year, the Home in the Sky attracted 300,000 visitors. As novel as the Home in the Sky was, however, the Builders Exchange wanted to ensure that there was always something new to see so that Cleveland’s would make return visits. In May, as Clevelanders’ attention turned to the outdoors, it debuted a “summer cottage” and horticultural exhibition on the 18th floor and partnered with a number of local organizations to offer an eight-day gardening clinic. To make the garden as useful as possible, the exhibit builders hauled in tons of soil donated by gardeners all over Cuyahoga County and representing common types in the Cleveland area: “Raw Parma subsoil that has not seen the light of day for 6,000 years is there. Then there is well worked clay loam from the W. G. Mather estate, prize winning garden soil from Lakewood, the much maligned but fertile soil of downtown Cleveland, sands of Euclid Avenue, clay of the Heights. Your soil will be represented,” one newspaper article assured. The exhibit also displayed a flagstone terrace, a hedgerow, shrubs, and a backyard garden with “onions, spinach, beets and other homely vegetables.”

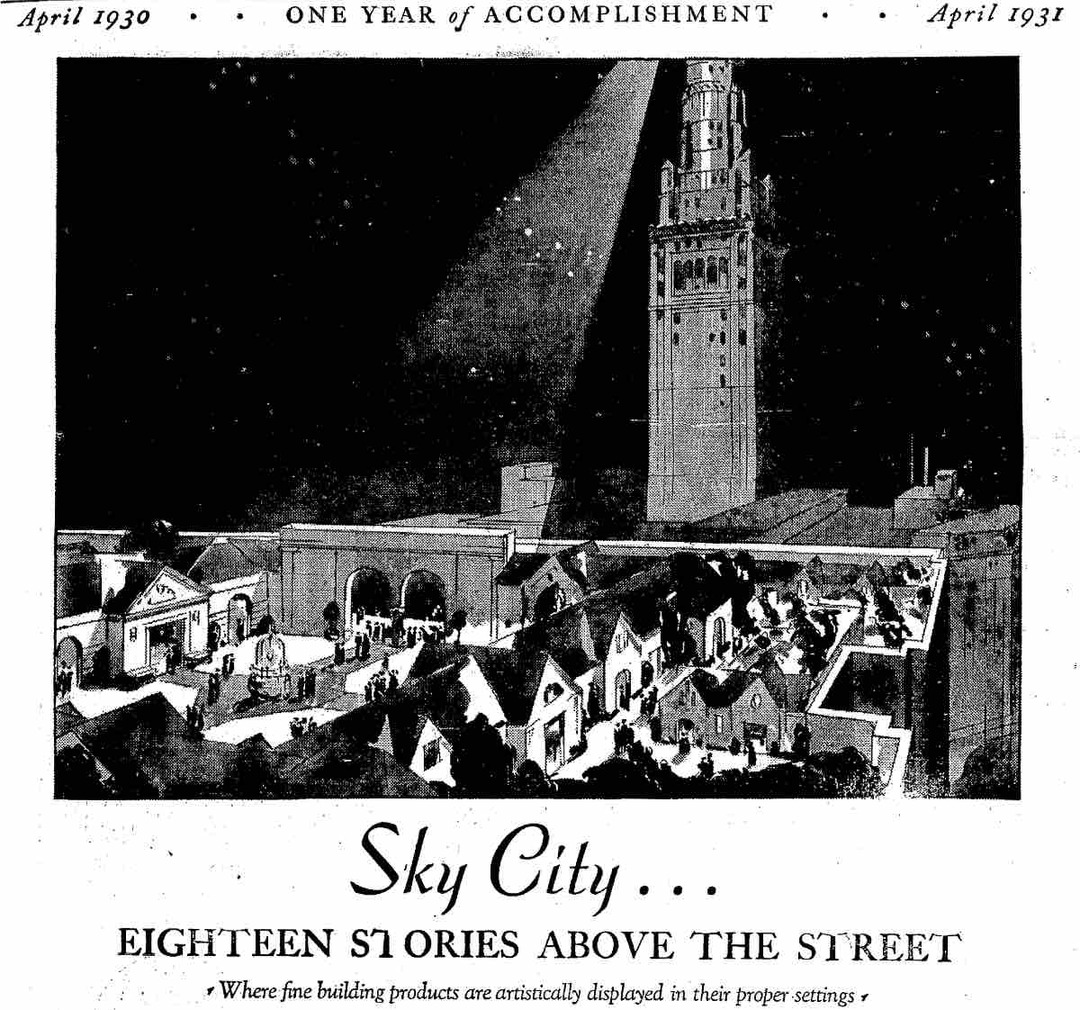

For a time, updates continued. In the fall of 1930, the Home in the Sky received a top-to-bottom refurnishing, this time by Higbee’s. The following spring, it opened a new exhibit called Sky City, a model streetscape lined by rows of homes exhibiting “building products in their proper settings.” It also featured the “Court in the Sky,” a courtyard to showcase different floor materials. In 1934, Kinney & Levan assumed responsibility for furnishing the Home in the Sky, along with the newest addition to the Builders Exchange exhibit, the American Institute of Architects Cleveland Chapter–designed “House of Tomorrow.” However, coverage of the Home in the Sky exhibit dropped precipitously thereafter. Occasional mentions suggest that it remained open but was not promoted. In 1941, the Builders Exchange moved to Euclid Avenue and East 18th Street and Sherwin-Williams took over its former space to house some of its operations formerly handled at its Canal Road facility. It is not recorded how the Builders Exchange dismantled the House in the Sky.

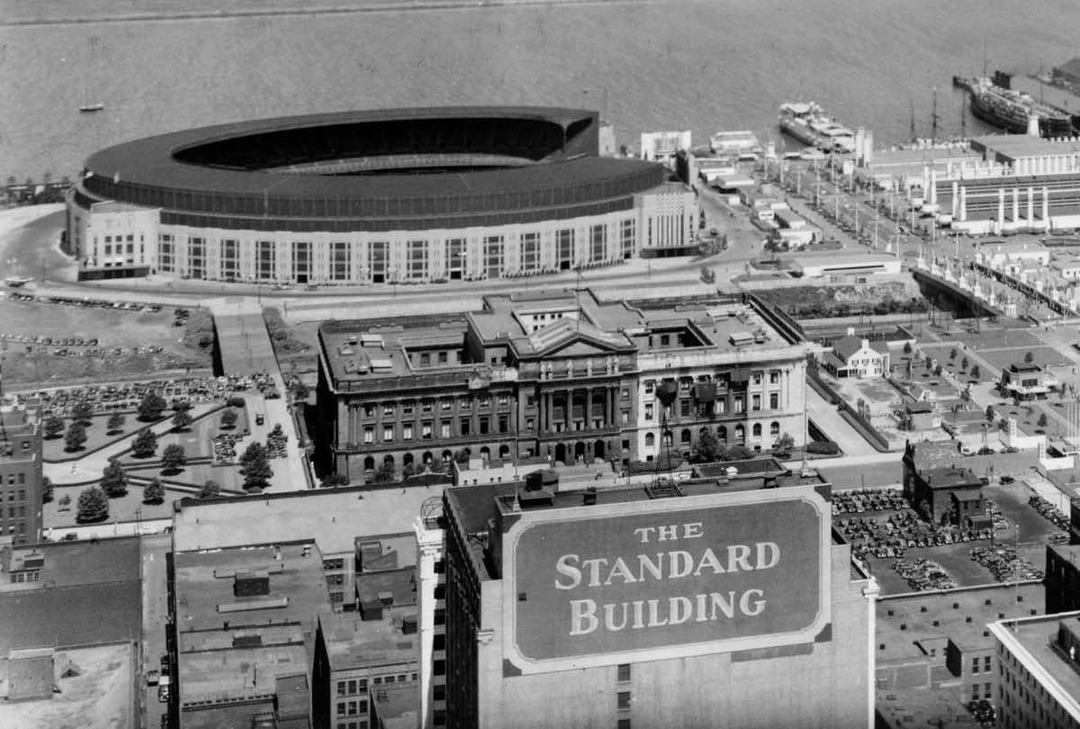

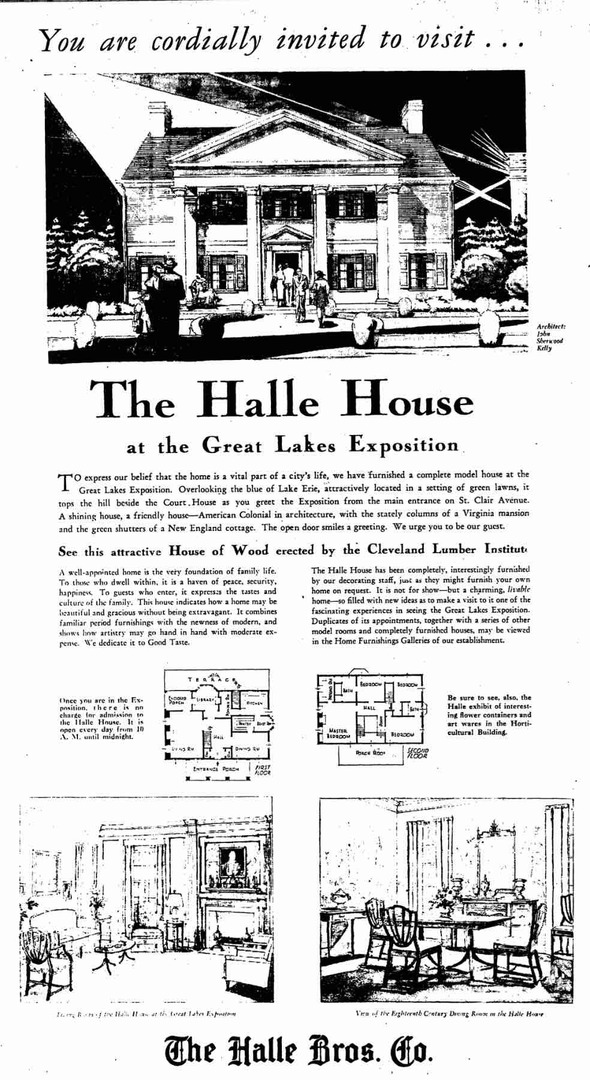

The Home in the Sky was surely one of the nation's most ambitious demonstration houses because of its novel location atop a skyscraper. But downtown Cleveland also saw several other demonstration houses in the 1930s. Four of them appeared on the grounds of the Great Lakes Exposition in 1936. Two of those served as commemorative replicas of the log cabins that had once housed early settler Lorenzo Carter and future President James A. Garfield. (Local interest in commemoration had led civic leaders to build a log cabin on Public Square for the city’s 1896 centennial and would later inspire a replica of Carter’s cabin in the Flats on the occasion of the U.S. Bicentennial in 1976.) In contrast, the other two were showcases for the home construction and real estate industries. Nestled between City Hall and the Cuyahoga County Court House were a small brick demonstration house built by Cleveland Builders Supply Co. and a large wood-frame, columned mansion constructed by the Cleveland Lumber Institute and furnished by the Halle Bros. Co. The Halle House invited visitors to see how they could recapture the flavor of colonial Virginia in their own homes by shopping Halle’s. In 1939, yet another demonstration house, this one sponsored by the American Legion, opened to the public on Euclid Avenue at East 21st Street in front of the Legion’s headquarters (now the site of CSU’s Student Center). Known as the Low Cost Demonstration Home, the diminutive Cape Cod measured only 28 x 26 feet and surely reflected the harsh reality that a decade of depression posed for the building trades.

Two decades later, the city’s building trades had a new reason for downtown demonstration homes. Unlike in the context of the Great Depression, when the Builders Exchange attracted Clevelanders to the city center in hopes of inspiring them to build new homes on the suburban periphery, by the 1950s, civic leaders were grappling with the consequences of outward population movement for the central city. In 1955, on the cusp of federal urban renewal, the National Retail Lumber Dealers Association unveiled Operation Demonstrate on the Mall, adopting the slogan “Live Better Where You Are.” The organization split in half and hauled two “age-blacked shells” of houses from Charity Avenue (a street that would in a few years be obliterated for the St. Vincent urban renewal project) to the Mall, where they were rebuilt and renovated to become Operation Demonstrate’s Traditional House and a Contemporary House. After the demonstration ended, the houses were put up for sale, to be moved by the buyer. Ultimately, the houses were loaded onto a barge at the foot of East 9th Street and ferried fifty miles west to Huron, Ohio.

The Home in the Sky, along with other demonstration houses, was a symbol of the ascendancy of the idea of housing as a consumer product. Fearing the effects that the Great Depression (and, later, urban decay) might have on homeownership, those with a profit stake in the private housing market used demonstration houses to entice the public into a marketplace with countless materials and products that might make the American Dream their reality. In that sense, a visit to the Home in the Sky was not unlike how people today browse Zillow, watch HGTV, or visit the Home & Garden Show at the I-X Center for home buying, remodeling, landscaping, and gardening inspiration.

Images