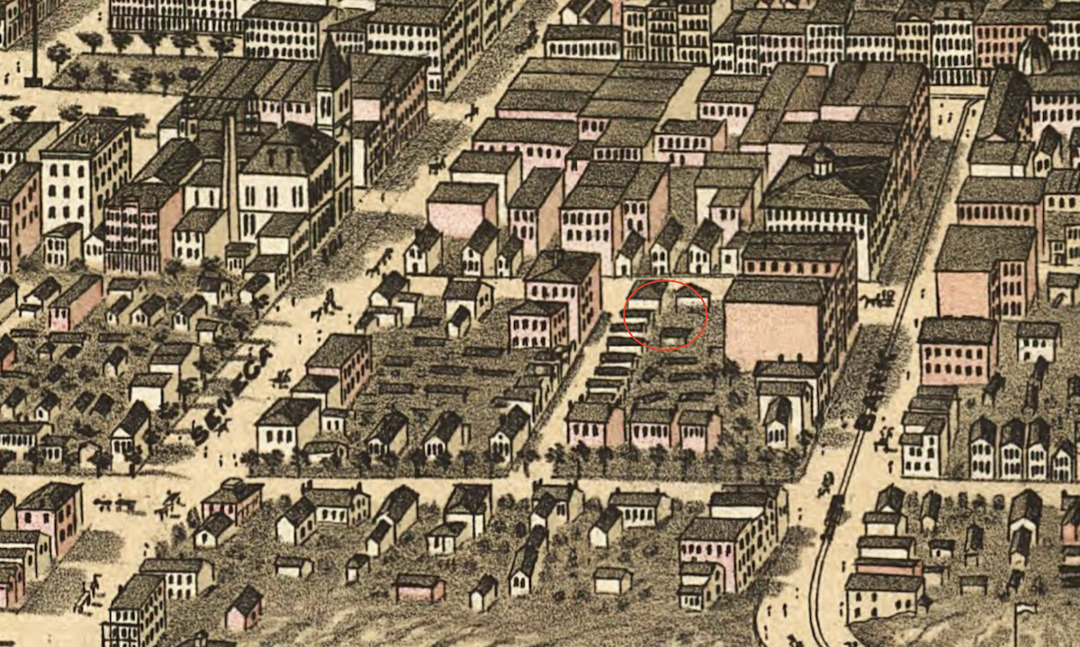

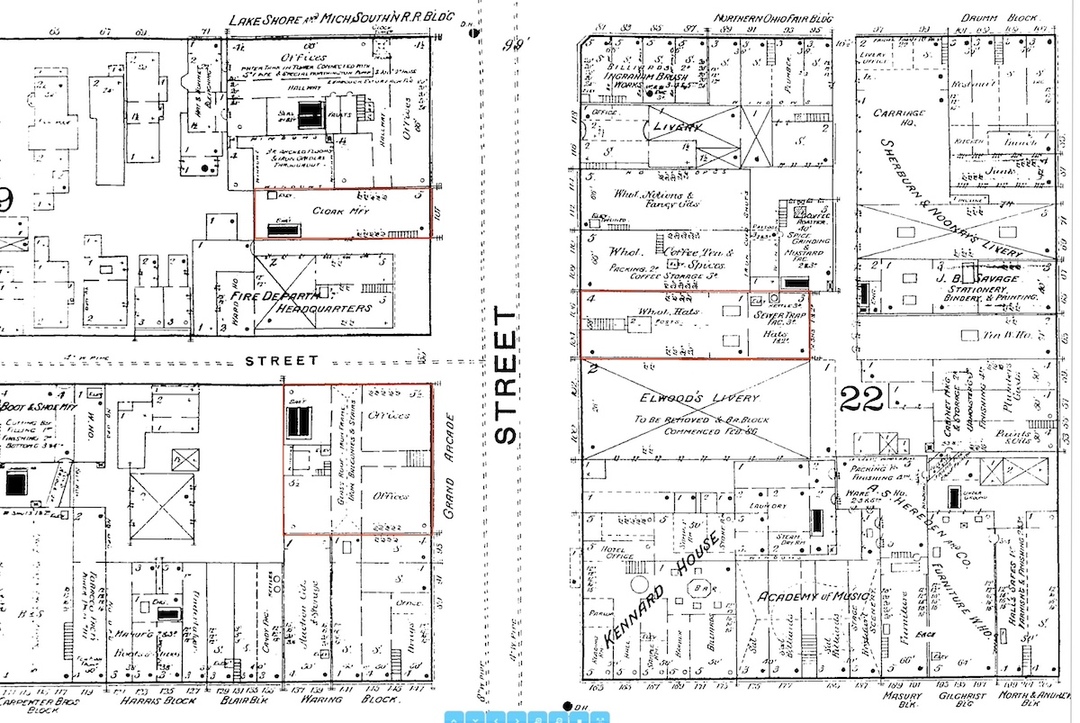

When its construction was completed in 1883, the six-story Grand Arcade on the northwest corner of St. Clair and West 4th was the tallest commercial building and most prestigious business address in Cleveland. Iron works, oil refineries and other industrial businesses rushed to lease offices in it. However, when the even taller and more prestigious Perry-Payne Building opened on Superior Avenue six years later, these businesses just as quickly left the Grand Arcade. This wouldn't be the last occupancy challenge this historic building would face .

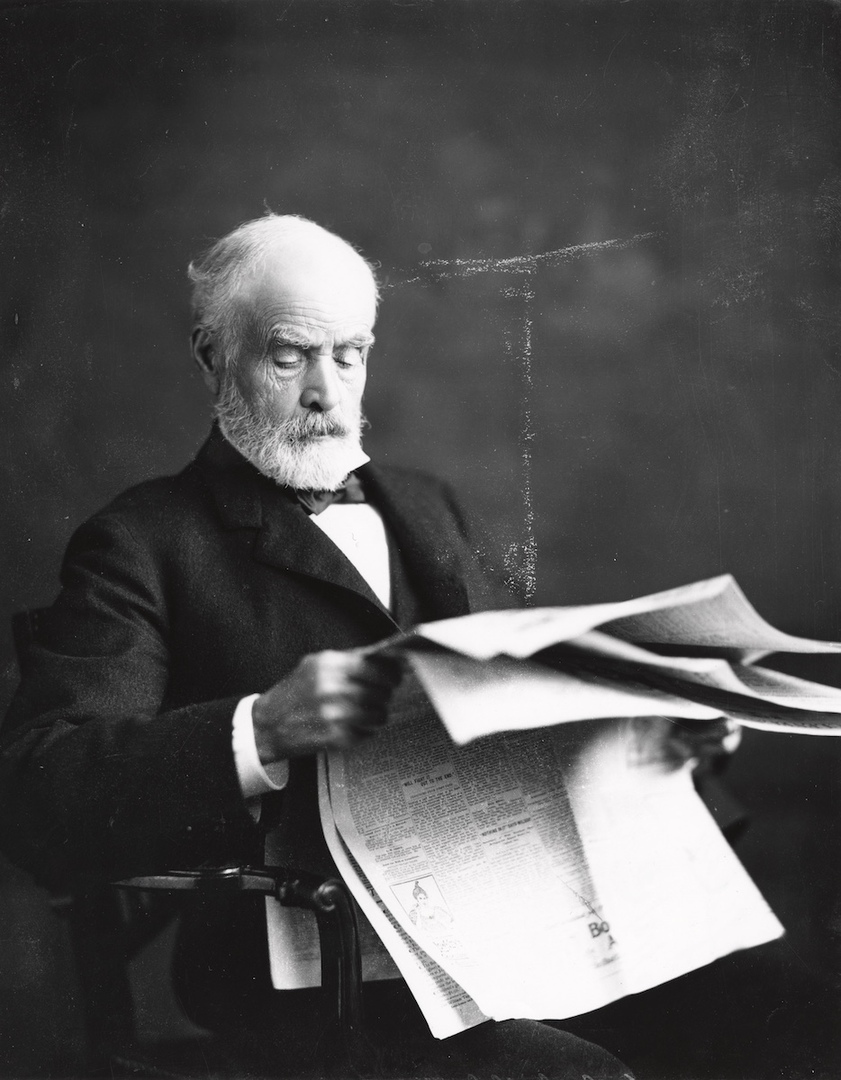

William Charles Scofield, the person for whom the Grand Arcade Building at 408 West St. Clair Avenue was built, was one of Cleveland's most prominent industrialists in the second half of the nineteenth century. He and John Alexander, reputedly the first person to refine oil in Cleveland, co-founded the Great Western Oil Works which, in the 1860s, was one of the chief competitors of John D. Rockefeller's Standard Oil Company. When, in 1872, Standard Oil Company engaged in anti-competitive acts and forced virtually all of Cleveland's oil refiners, including John Alexander and William Scofield, to sell their refineries to it at discounted prices, Alexander retired from the refinery business and returned to England. Scofield, however, did not. He not only survived the so-called "Cleveland Massacre," but thrived after it.

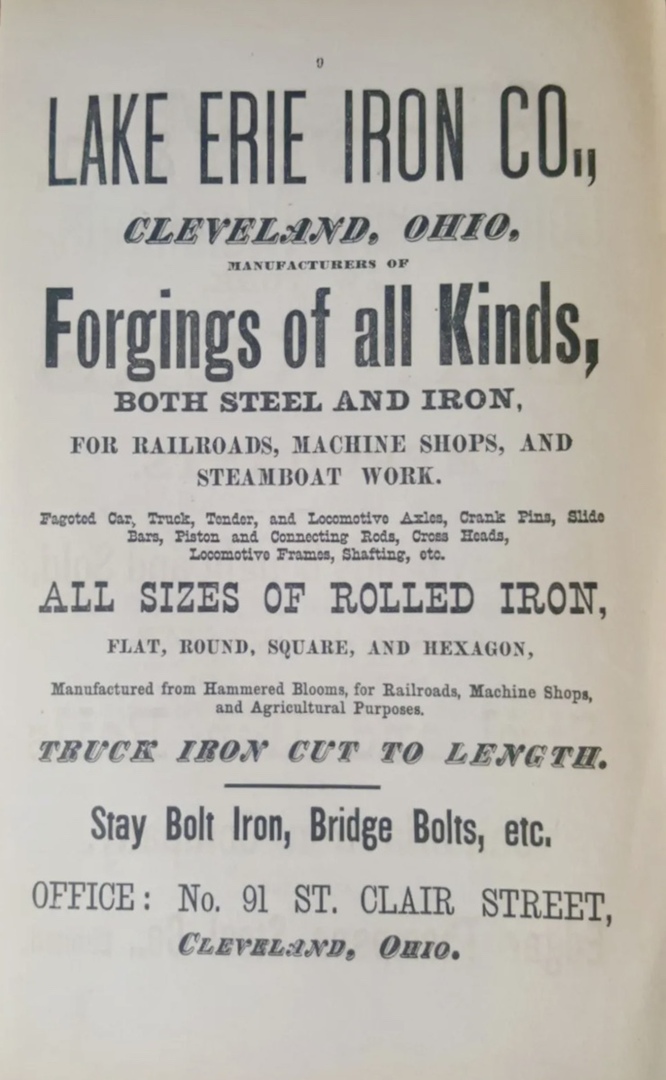

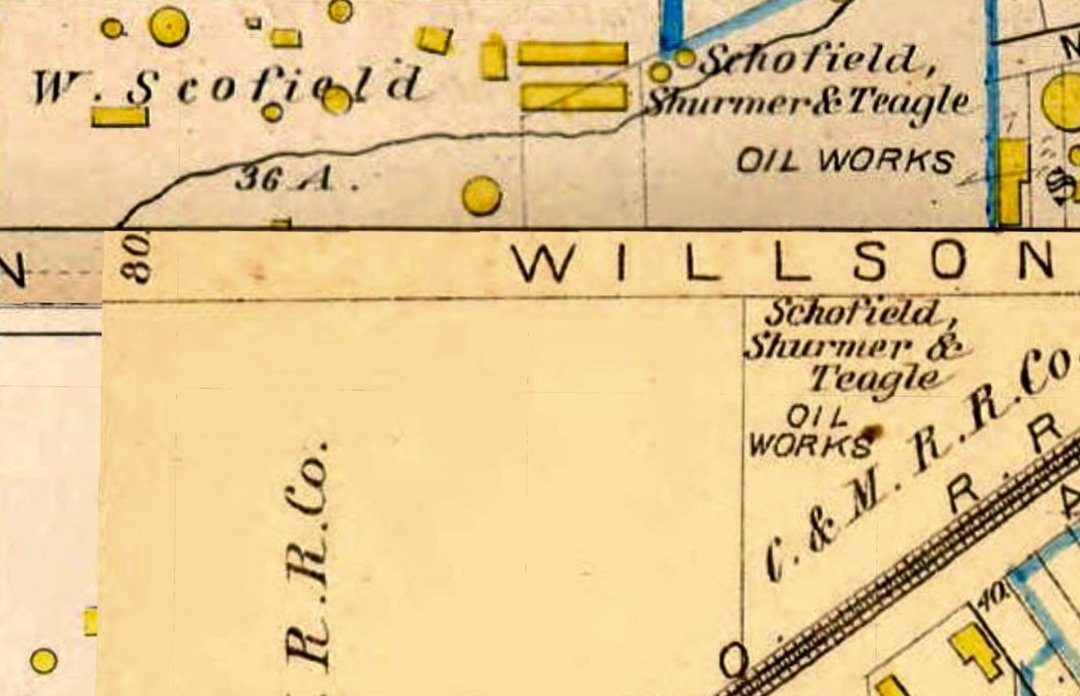

In 1872, the same year that he was forced out of the oil refining industry by Rockefeller's Standard Oil Company, W. C., as Scofield was known, entered the iron manufacturing industry, purchasing the historic Otis Iron Works on Whiskey Island. He renamed it Lake Erie Iron Company, expanded its operations to include a new facility for the manufacture of nuts and bolts on land located between East 63rd Street and Addison Avenue close to the tracks of the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railroad, and made it a very successful business. In 1874, two years after the Cleveland Massacre, Scofield formed a new partnership, built a new oil refinery on Willson Avenue (East 55th Street), north of Broadway and near the tracks of the Atlantic and Great Western Railroad, and re-entered the oil refining business, operating once again as Great Western Oil.

In 1882, W. C. Scofield decided to construct the Grand Arcade. Yet, it wasn't his first presence on St. Clair or even the first building he had erected on that street. After immigrating from England and arriving in Cleveland in about 1844, he and his wife Ann had settled on St. Clair Street, where their first two children were born. In 1850, they had moved east to Hamilton Street as the neighborhood northwest of Public Square (today known as the Warehouse District) began its mid nineteenth century transformation into a commercial district. Despite moving his residence, Scofield retained a presence on St. Clair, starting up several small manufacturing businesses there in the 1850s and early 1860s.

In 1864, the same year in which he formed his partnership with John Alexander, William Scofield had expanded his business presence on St. Clair by purchasing the former homestead of pioneer Cleveland grocer and wholesale liquor merchant Nelson Monroe, which was located nearly directly across the street from where the Grand Arcade would be built almost two decades later. The offices of the Great Western Oil Company were located on this property from 1864 to 1868. In 1878, Scofield had further solidified his presence on St Clair by building the four-story brick and stone Scofield Block on the property. A number of industrial tenants, including Scofield's Lake Erie Iron Company, soon moved their offices into that building.

So why did W. C. Scofield decide in 1882 to build the Grand Arcade across the street from the Scofield Block built just four years earlier? It is not clear from recorded sources why he did so, but it may have been to expand his influence in the industry in which he was most personally and financially invested—coal and iron. Whatever the reason, in February 1882, Scofield purchased the lot on the northwest corner of St. Clair and Academy (West 4th) and hired Cleveland architect Levi T. Scofield to design an office building for that lot which had 100 feet of frontage on St. Clair and 97 feet of frontage on Academy. Levi Scofield, who does not appear to have been a relative of W. C. Scofield—at least not a close relative—is best known to Clevelanders today as the architect of both the Soldiers and Sailors Monument on Public Square and the Schofield Building on the southwest corner of East 9th Street and Euclid Avenue.

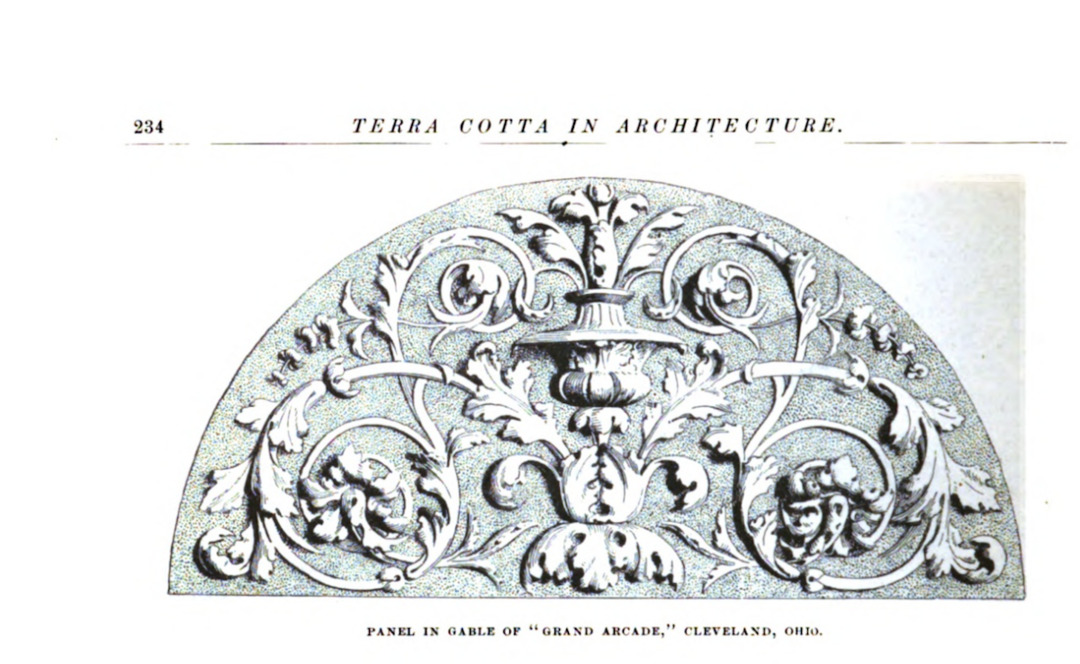

Like some of the other buildings Levi Scofield designed, the Grand Arcade was designed to be grand and notable. Years after it was built, it was referred to by at least one newspaper as Cleveland 's first "modern" office building. Designed in the Neoclassical Revival style with elements of Neo-Grec, it is a brick and stone building that stands six stories tall (five floors above ground with a raised basement). Its exterior walls fronting St. Clair Avenue and West 4th Street are decorated with pilasters, capitals, belt courses, entablatures, ornamental swags and other details formed from cut sandstone and unglazed terra cotta. The construction cost of the building was $100,000 ($3 million+ in 2024 dollars).

One of the most notable features of the Grand Arcade's original design was its approximately 100 by 20 foot, five-story-tall interior court which had an ornate triangular prism-shaped glass skylight above it. All of the building's interior offices had direct access to this court from iron balconies and descending stairs. Regrettably, that interior court no longer exists. Although no record has been found that documents when it was removed, it likely occurred during one of the several renovations of the building that took place between 1902 and 1962.

Another mystery associated with the Grand Arcade is: Why did W. C. Scofield decide to call this building an "arcade?" That term traditionally refers to a building with a covered passageway lined with retail shops on both sides. An article in the Cleveland Leader, on December 7, 1912, noted that "the building actually is not an arcade and received its name from the court and its many balconies opening from the inner office suites." However, there is no indication that the newspaper had obtained that explanation from W. C. Scofield who was still living at the time the article was published, and there may have been a reason, other than the explanation offered by the Leader, why Scofield used the term. There were, in fact, retail shops located on the first floor of the building in the decades of the 1880s and 1890s and some of these could have had interior storefronts and entrance ways on the court.

When the Grand Arcade opened in 1883, it notably drew as its first tenants a large number of companies from the coal and iron industries, some of which had previously been tenants in the Hilliard Building on Water (West 9th) Street which had been known since 1875 as the Coal and Iron Exchange Building. According to information gleaned from the 1884-1885 Cleveland Directory, the Grand Arcade in its first full year leased office suites to 14 iron manufacturing companies and five coal companies. However, when the Perry-Payne building opened in 1889, all of the iron manufacturing tenants, except Scofield's Lake Erie Iron Company, and all but two of the coal tenants left the Grand Arcade.

It appears, again from a survey of tenant listings in Cleveland directories, that W. C. Scofield attempted to address the departure of coal and iron companies from his building by seeking, in the 1890s, to attract oil and railroad companies. For a time he was successful in that effort, helped by the fact that so many railroads and streetcar companies had located their offices in buildings on St. Clair between Seneca (West 3rd) and Water (West 9th) that that stretch of St. Clair was known as Railroaders' Row. But just as the opening of the Perry-Payne Building in 1889 had impacted the Grand Arcade's efforts to attract and keep coal and iron companies as tenants, the opening of additional new downtown office buildings in the 1890s, including the Society for Savings Building and the Arcade in 1890, the Western Reserve Building in 1892, the Garfield Building in 1893 and the New England Building in 1896, similarly impacted the Grand Arcades's efforts to attract tenants from other industries. By 1899, only one oil company and just three railroad companies remained as tenants in the Grand Arcade. In that same year, W. C. Scofield, who was already in his late seventies—although he would live to be 95 years old—turned over ownership and control of the building to his sons Charles and Frank. They, likely with their father's blessing, took a new approach to dealing with the building's growing occupancy problem.

In 1902, the Grand Arcade was remodeled and transformed from an office building into what was then called a "power block," i.e., a building occupied by a single tenant. It was a good decision for the Scofield family which would continue to own the Grand Arcade and lease it to a series of single tenants until they sold the property in 1955. From 1902 until 1912, the building was leased to North Electric Company, a telephone manufacturing company. Then, from 1913 until 1926, it was leased to Clawson and Wilson, a wholesale drug company headquartered in Buffalo, New York. Finally, from 1926 until 1961, the building was occupied by the Standard Drug Company, a Cleveland retail and wholesale company, which used it as a warehouse and purchased the building from the Scofield family in 1955. Standard Drug sold the Grand Arcade in 1961 to a realty company. The following year, the building was purchased by the non-profit City Mission which remodeled and converted it into a homeless shelter.

After occupying the building for almost three decades, the City Mission sold the Grand Arcade in 1991 to a for-profit limited partnership which restored and renovated the building, converting it to a new residential use, first as market-rate apartments and later as condominiums. In the second phase of the project, three other historic Warehouse District buildings were added to the Grand Arcade condominium development—the Waring Building, built in 1855 and located on St. Clair adjacent to the Grand Arcade; the Klein-Marks Building, built in 1881 and located on West 6th Street just north of the Waring Building; and the Blair Building, built circa 1868 and located just north of the Klein-Marks Building.

From Cleveland's tallest office building and most prestigious address; to a "power block" for single commercial tenants; to a wholesale drug warehouse; to a shelter for Cleveland's homeless; to market-rate apartments; and finally to residential condominiums, the Grand Arcade has endured more use changes than most of Cleveland's other historic buildings. Through it all, the Grand Arcade, much like the nineteenth century industrialist who built it, has not only survived, but has thrived.

Images