In the 1960s Mayfield Heights was enjoying a warp-speed shift from sleepy rural backwater to bustling residential and commercial hub. This also was the case for many recently incorporated “automobile suburbs”—locales like Brook Park and Middleburg Heights, whose populations were being supercharged by the construction of nearby freeway interchanges and the white-flight relocation of city and inner-ring-suburban residents. Vast increases in Russian, Italian, and Jewish residents typified Mayfield Heights; but two things about the city also drew visitors by the thousands. First was a flood of early big-box stores—Gold Circle, Uncle Bills, and Topps—forerunners of today’s Walmarts and Targets. But the second distinction was way more entertaining than strolling through a mundane discount store. Simply put, Mayfield Heights was an epicenter of recreation. Facing Mayfield Road just west of SOM Center Road was The Giant Slide—twelve lanes of slippery and tolerably dangerous fun. Nearby, trampolines and an Arnold Palmer Putt-Putt course hosted myriad date-nights and group outings. A quarter mile away, toward the back of Golden Gate Plaza, a gigantic roller rink welcomed seasoned and novice skaters. The floorboards of the mall’s Half-Price Books store are believed to be from the Roller Palace. Look closely and maybe you’ll see the butt-print of a hapless skater. A slot car raceway at Mayland Shopping Center drew thousands of enthusiasts, and in a field behind the Golden Gate Plaza, visits from the Big Top Circus were a regular occurrence.

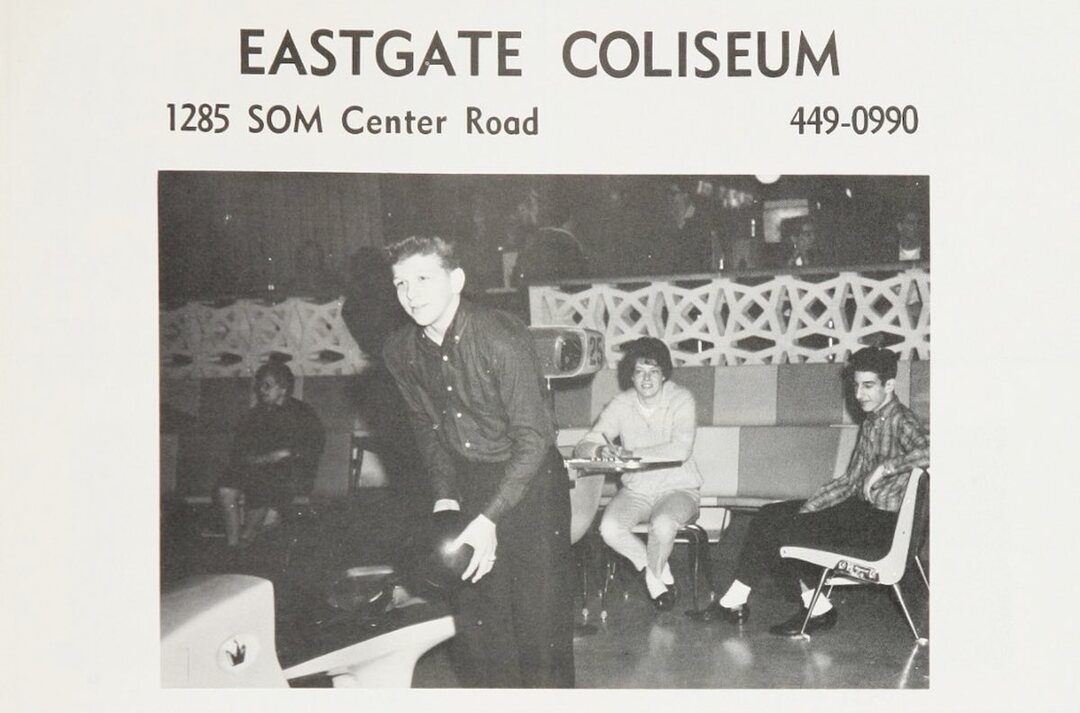

But the don of east-side entertainment stood at the back of Eastgate Shopping Center on the current site of a Target store. A palatial but architecturally uninteresting structure with a somewhat sordid underside: This was the Eastgate Coliseum.

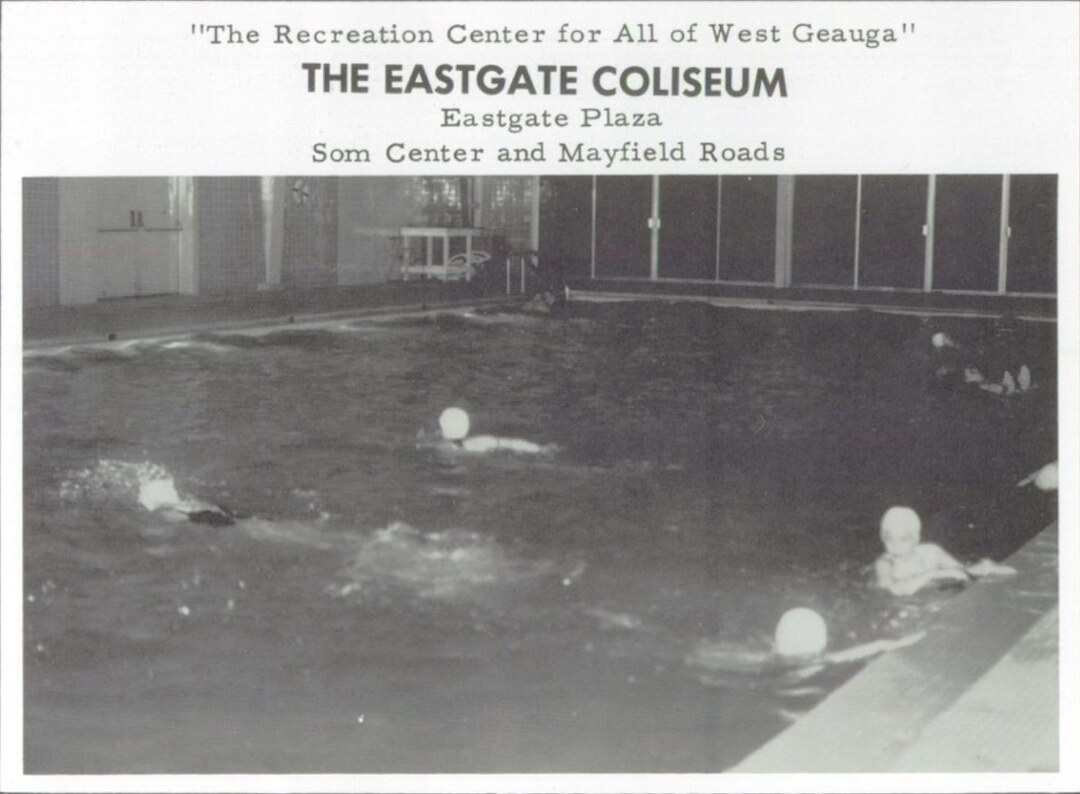

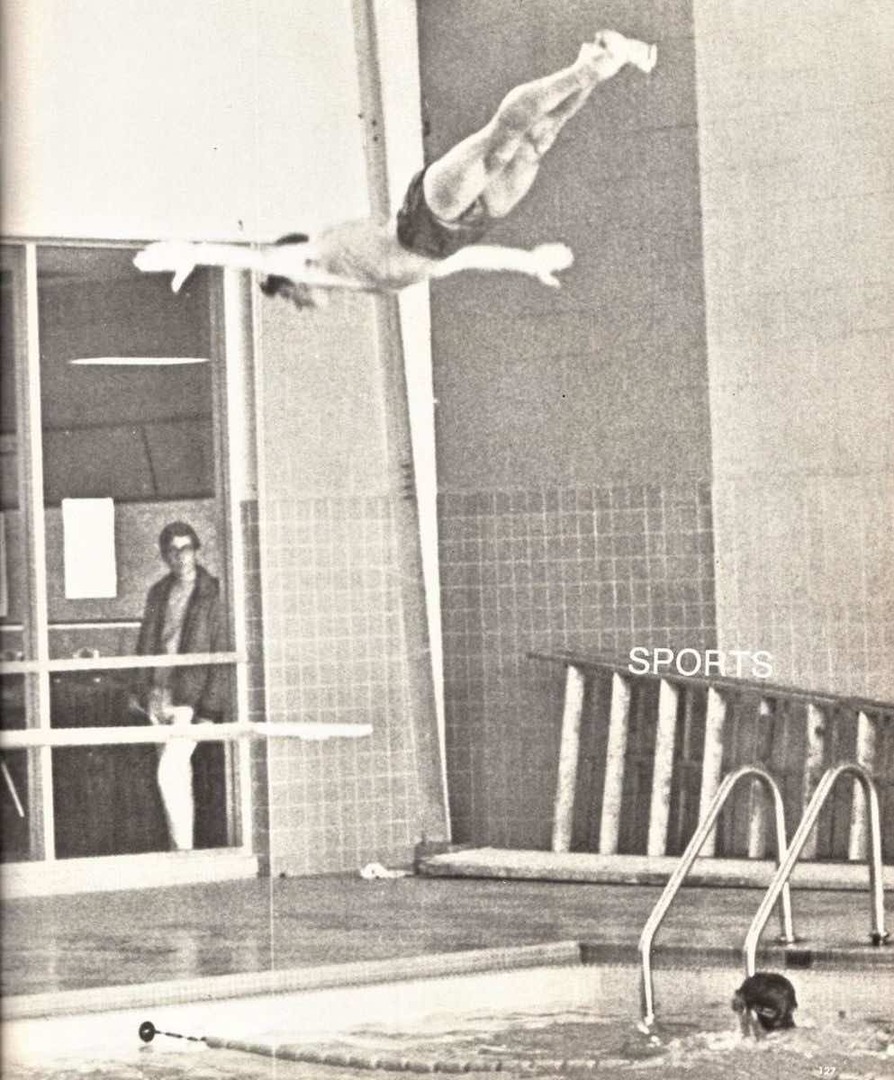

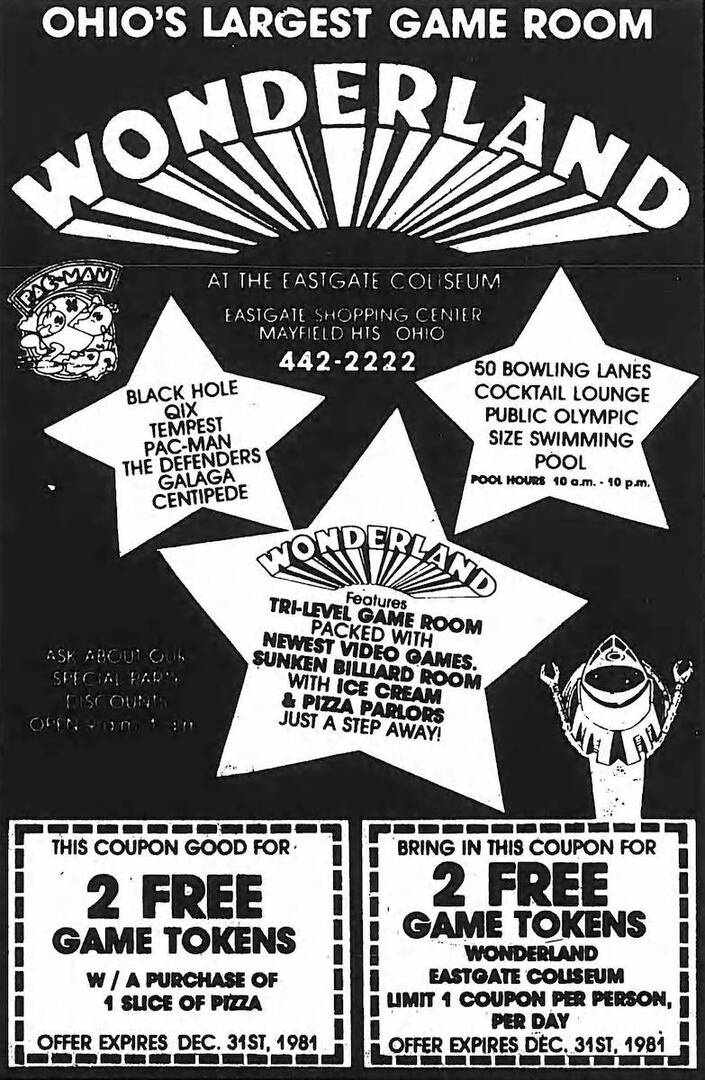

The Coliseum had something for everyone. Miniature golf, martial arts room, and a nursery brought in families. Fifty lanes of bowling awaited drop-ins, league players, and professionals. A banquet hall hosted birthday parties, wedding receptions, all-night after-prom parties, and bar mitzvahs. A colossal game room—The Wonderland—featured everything from billiards to Skee-ball to Astroblaster. There was even an Olympic-size indoor swimming pool that saw added duty as a practice venue for several suburban high school swim teams. Some patrons later recalled that the pool had so much chlorine that their bathing suits turned colors.

For those over 18—or kids in possession of an authentic-looking ID—the Coliseum also sported a lounge called the In Spot with two stages and two bands every weekend. Over the years, scores of fresh-faced locals performed there: Tony & the Twilighters, The Charades, Robo & the Turtles, Bocky Boo & the Visions. The Twilighters even scored a local hit record with "Be Faithful" in 1966. National acts such as Lesley Gore, Tony Orlando and Dawn, and Wilson Pickett also performed at the Eastgate Coliseum. The In Spot closed in the late 1960s, ostensibly due to frighteningly frequent fights among patrons. As one observer remembered, cops clutching binoculars scanned the parking lot from the roof to head off trouble.

The Eastgate Coliseum opened in January 1961, but its genesis dates to 1957. This was the year that notorious Teamsters Union president Jimmy Hoffa took control of investing the huge amounts of money pouring into the Union’s Central States Pension Fund (CSPF). Prior to 1957, a variety of banks had managed most of CSPF’s money, funneling it into high-grade common stocks, corporate bonds, and governmental securities. But Hoffa wanted more, which meant far-riskier ventures, principally the holding of mortgages on hotels like Miami’s Castaways and Las Vegas’s Caesar’s Palace, Sands, and Stardust. According to a Forbes magazine article, “Hoffa also arranged for substantial loans to mobsters who were partners in Las Vegas casinos and Southern California real estate developments.” CSPF also made several real estate investments in the Cleveland area. In fact, the first mortgage let by the Fund’s trustees was a $1 million mortgage on the Cleveland Raceways track in Willowick. U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy later challenged the prudence of this investment and Cleveland Raceways terminated the relationship. However, the Raceways investment defined the nature of most subsequent CSPF investments. As noted in Jerome Skolnik’s House of Cards, “By 1974, while other pension funds held 1.8 percent of their assets in mortgages, 58.3 percent of the Teamsters Central States Pension Fund’s assets were mortgages.”

In 1961 the Central States Pension Fund trustees followed a similar pattern to the Cleveland Raceways investment with the construction of the Eastgate Coliseum. Secured by a roughly $1 million loan from the CSPF, the deal was brokered by a group of speculators headed by Ohio Teamsters president William Presser and his son Jackie Presser. According to The Wall Street Journal (July 1972) there existed a “long standing Pension Fund rule authorizing kickbacks of no less than 10% of the total of the loan;" and this was likely the case (albeit never proved) with the Coliseum. Only a year before, incidentally, William Presser had been convicted of obstruction of justice.

Controversy dogged the Coliseum within a year of its opening. In August 1962, three African American teenagers were refused admission to the pool. Following demonstrations by the NAACP, the Coliseum committed to an anti-discrimination policy. Two years later, in January 1964, CSPF foreclosed on the Coliseum, claiming that Eastgate Investment Co. owed more than $1 million in principal and unpaid interest on three mortgage loans. At the time, the president of Eastgate Investment Co. was none other than Jackie Presser, who had purchased the facility from the original owner, Marvin Bilsky, who also headed the Cleveland & Sandusky Brewing Co. William Presser was listed as a trustee of the Pension Fund, along with Jimmy Hoffa. By late September the Coliseum was put up for auction and subsequently purchased by (guess who?) the Central States Pension Fund.

After the mid 1960s, the Eastgate Coliseum managed to stay mostly out of the newspapers, save for a 1973 drowning; hundreds of help-wanted ads, bowling scores, and public events announcements; and periodic flareups over the exorbitant salaries paid to union officials. (Indeed, by the mid 1970s, William Presser was reputedly the highest-paid union official in the world.) However, the Teamsters, the CSPF, and their officers and local affiliates garnered headlines on a stunningly regular basis. In 1971, William Presser was convicted of illegal shakedowns of local businesses. In 1977 Jackie Presser, Teamsters President Frank Fitzsimmons, and other Teamster leaders were forced to resign as trustees of the CSPF—charged with making improper loans to mob-controlled Las Vegas casinos, racetracks, and real estate ventures. By the late ’70s both Pressers had become Mob-focused informants for the FBI and transcripts of wiretaps linked each to organized crime figures. Shortly before his death in 1981, Bill Presser was forced to resign the vice presidency of the International Union of Teamsters after he was convicted of extortion and obstruction of justice. Jackie Presser succeeded him and, very shortly after, the U.S. Department of Labor began investigating Jackie for allegedly padding the Teamsters Local 507 payroll with "ghost employees." In April 1983, then President Roy Williams was convicted for conspiring to bribe a U.S. Senator. In May 1986, Jackie Presser was targeted in a fraud investigation by federal prosecutors. Through it all, the Eastgate Coliseum lived on—until the mid 1990s when, in a literal sense, it too became a Target.

Images